Edible Native Plants...and My Quest for a Rare Toronto Persimmon Tree

Native North American Fruits and Nuts (including persimmon and pawpaw!)

By Steven Biggs

Ontario Native Edible Fruits and Nuts

Pointing to two trees, Tom Atkinson explains that we have the makings of a golf club.

“There you have the shaft of the club; here you have the head,” he says, pointing from one tree to the other:

The shagbark hickory, with a bit of give in the wood, is ideal for the shaft.

The American persimmon, as part of the ebony family, has extremely hard wood that is suitable for whacking the ball.

Both are native North American species; and both have edible parts.

Hunting Pawpaw and Persimmon in Toronto

Our tree trek today is the result of my interest in another North American native, the pawpaw tree.

Because of my fascination with pawpaw, I tracked down Atkinson, a Toronto resident and native-plant expert, whose backyard is packed with pawpaw trees.

After I visited his yard and soaked up some pawpaw wisdom, he mentioned a fine specimen of American persimmon growing here, in Toronto.

I took the bait.

Under a Toronto Persimmon Tree

Now, in the shadow of that persimmon tree, I’m learning far more from Atkinson than persimmon trivia:

The nut of the shagbark hickory, a large native forest tree, is quite sweet.

He points to a pin oak, explaining that the leaves are often yellowish here in Toronto, where such oaks have trouble satisfying their craving for iron.

Waving toward a couple of conifers, Atkinson explains that fir cones point upwards, while Norway spruce cones point down.

There’s stickiness on the bud of American horse chestnuts, but not on their Asian counterparts.

And while the buckeye nut is normally left for squirrels, he’s heard that native North Americans prepared it for human consumption using hot rocks.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

A Backyard Native Fruit Food Forest

In his own garden, Atkinson’s focus is on native trees and shrubs. Many of them are considered Carolinian and are, here in Toronto, at the northern limits of their range.

My own interest in native trees and shrubs has gustatory motivations, but Atkinson’s came about because of his woodworking hobby. “I thought, if I was using wood, I should be putting it back,” he explains. While no longer woodworking, he still has a garden full of native trees and shrubs.

The edible native North American fruit and nut trees in his backyard food forest include sweet crabapple, black walnut, bitternut hickory, red mulberry and beaked hazelnut. “It is really for the creatures of the area, all this bounty,” he adds. I’m taken aback by his generous attitude towards harvest-purloining wildlife, but it’s consistent with his approach of putting something back.

Find out about elderberry, a native fruit bush.

American Persimmon

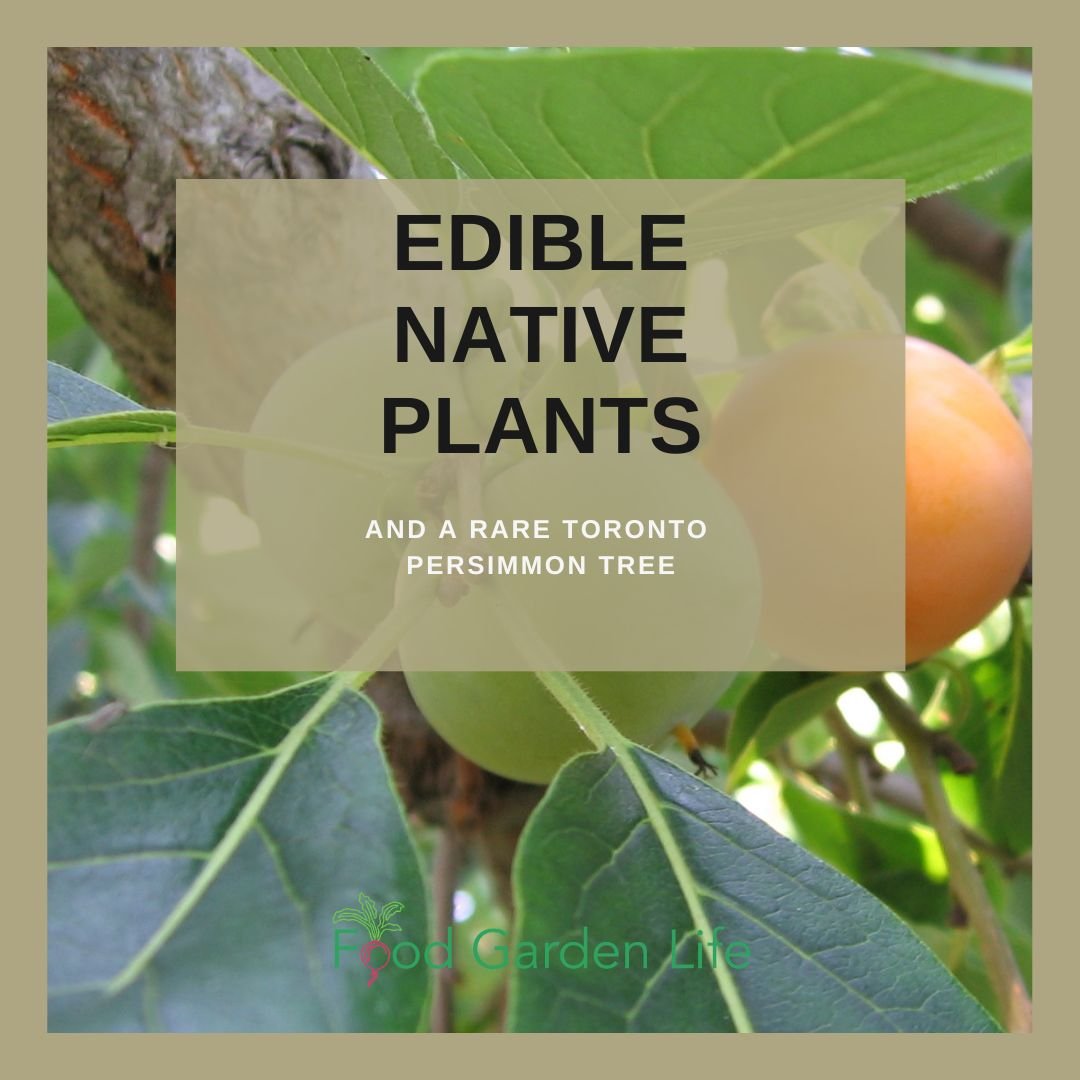

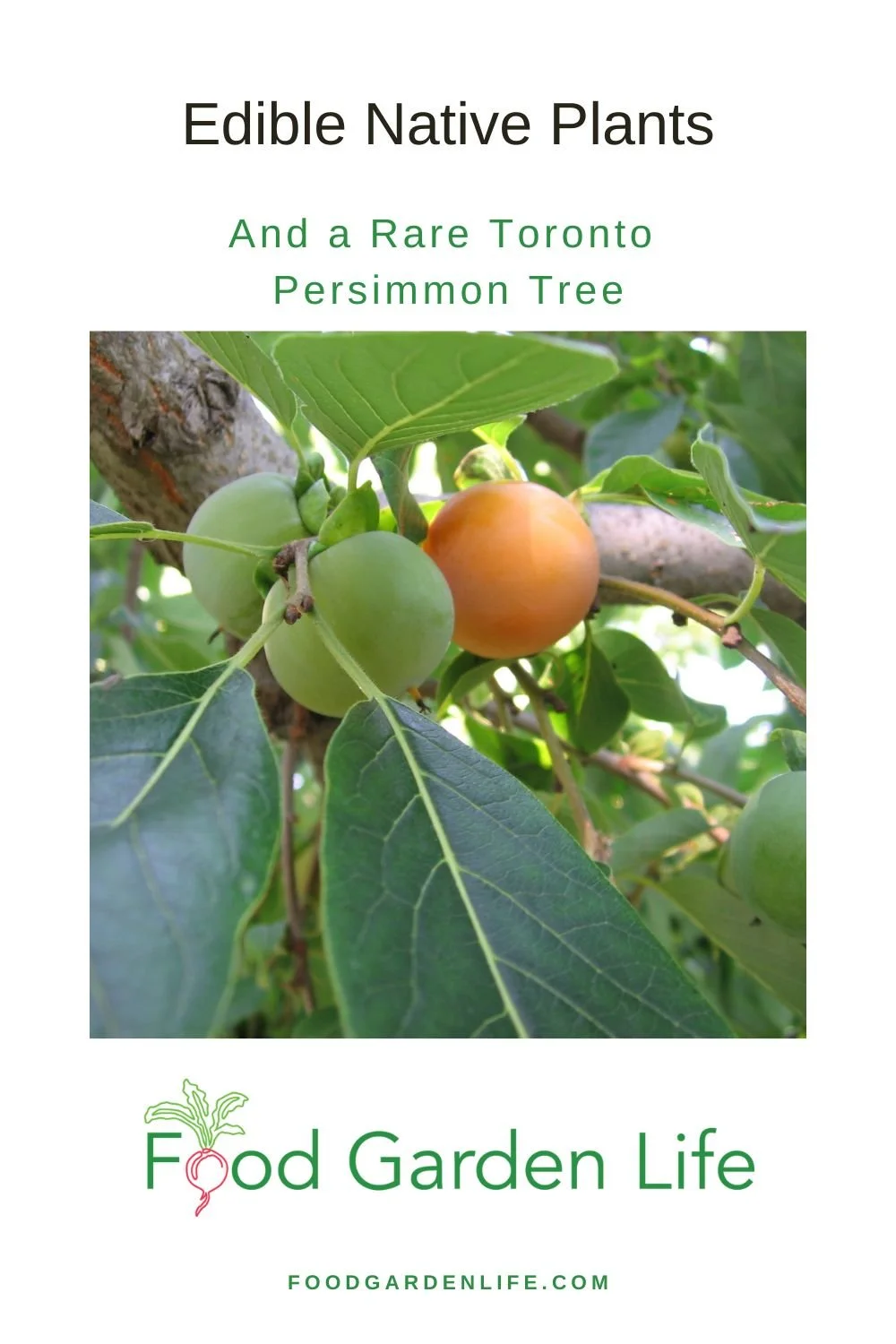

In the shadow of an American persimmon in Toronto. Grow persimmon in the warmer parts of Ontario.

Sitting under the American persimmon tree and looking up, I’m dismayed to find that the fruits are still green. Atkinson cautions that the fruit are astringent and bitter when unripe, so I satisfy myself with snapping pictures.

He explains that although this is a native North American species, it doesn’t usually grow wild this far north. But it grows well under cultivation.

(I found ripe, orange American persimmons a week later at Grimo Nut Nursery in Niagara, where the more temperate climate aids in ripening fruit earlier than in Toronto. They are sweet and velvety on the tongue; I’m delighted that the young persimmon tree I’ve been nurturing in my garden will have been worth the effort when it starts to fruit. And the fruit-laden trees are beautiful.)

Pawpaw

Atkinson's Toronto backyard, where he grows pawpaw trees and other native fruit trees.

Pointing to clusters of mango-like fruit, Atkinson says, “The fragrance of the pawpaw when ripe is aromatic.” He finds that the texture is like custard.

Each fruit usually contains four to eight seeds. “Like a watermelon, spit out the seeds,” Atkinson adds.

Don’t wait too long to pick it. “If it’s starting to turn brown, give it to the squirrels or raccoons,” he advises.

Pawpaws can be found growing wild on the north shore of Lake Erie into the Niagara region. Like the American persimmon, you’re not likely to find wild ones here in Toronto, but they do grow well here when planted. The large, lush leaves add a tropical feel to the garden.

Serviceberry

Serviceberry is a native edible plant well suited to growing in the city.

When it comes to native edible plants, Atkinson believes that one of the best to grow in the city is the serviceberry.

“There’s a whole bunch of them,” he explains, listing the related members of the serviceberry (Amelanchier) clan. They all have in common an edible fruit similar in size to a blueberry.

Palatability varies by species and variety. The saskatoon berry, which is also grown commercially, has consistently good fruit quality, according to Atkinson.

Serviceberry is widely planted in Toronto parks and is common in the nursery trade. They can be grown as a small tree or a bush.

In my own garden, I end up sharing my serviceberry harvest with robins if I don’t pick them quickly enough. Atkinson says that cedar waxwings like them, too.

Aside from the fruit, the serviceberry leaves turn a vibrant orange-red in the fall and the bark, smooth and grey, is showy, too.

Here’s a member of the serviceberry family that’s grown as a commercial crop: Guide to Growing Saskatoon Berries: Planting, Pruning, Care

American Hazelnut

Pin this post!

American hazelnut is a native nut bush. It’s related to the European hazelnuts sold in grocery stores, but the nuts are smaller.

Hazelnuts send out attractive catkins in late winter, before any leaves are out.

Crabapple

“They’re a delight to look at,” agrees Atkinson as we change gears and talk about the sweet crab, a wild crabapple. “It puts on a really good show of flowers,” he says as he describes a blush of pink on white flowers in the spring, adding, “It’s as good as a flowering dogwood but in a different sort of way.” The fruit is very waxy, and very attractive, having a greenish yellow colour.

“Squirrels don’t touch it,” he exclaims. He likes the fall leaf colours, which range from yellow to burnt orange.

On the culinary side, he says the sweet crab fruit is sour, but a perfect accompaniment when roasted with a rich meat such as pork, where the tartness of the fruit cuts the richness of the meat.

Black Walnut

Atkinson speaks warmly of towering black walnut trees and of the beautiful dark wood they yield. He notes how common they are in the Niagara peninsula: “They’re almost like weeds.”

I agree with the weedy bit: My neighbour’s black walnut stops me from growing anything in the tomato family at the back of my yard. Despite its hostile actions towards my tomatoes, I have grown fond of sitting under that tree, never really considering why. “The shade under a walnut is really quite lovely,” he says, describing dappled light that results from the long leaf stalks adorned with small leaflets.

He discourages me from promoting the black walnut for edible uses because the nut meat is very difficult to extract: the shells are rock hard, requiring a hammer to crack. And the meat doesn’t come out easily like an English walnut, but has to be picked out. But by this point I’ve already decided to write about edible native plants because of their ornamental appeal.

Read about wicking beds, a way to deal with black walnut toxicity, a.k.a. juglone.

Find out how to garden successfully when there’s a black walnut tree nearby.

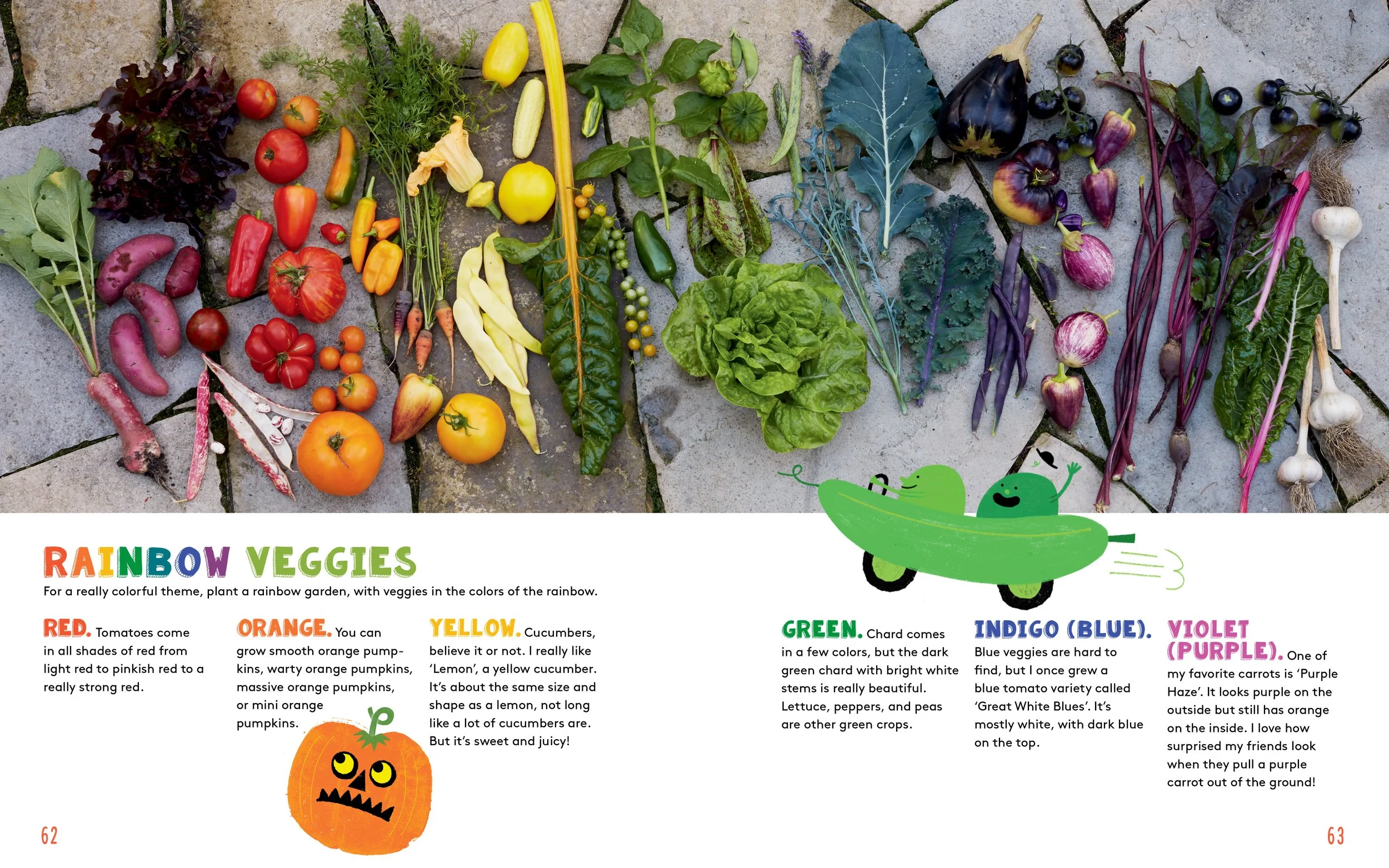

Growing Native Fruit in Urban Areas

I thank Atkinson for the tour and email correspondence. A couple of weeks later, Atkinson emails me a photo of a broken pawpaw branch. He writes: “Steve, here is what befalls a pawpaw when in an urban setting, and there are hungry raccoons about. I do not begrudge my masked friends at all for doing what inevitably they will do when after pawpaws.”

FAQ American Persimmon

Can persimmon grow in Ontario? Can you grow persimmons in Canada?

American persimmon is reported to be hardy into Canadian hardiness zone 4, though a long growing season with summer heat is needed for fruit ripening. Best in zones zones 5b-8.

Remember: Zones are only a guideline. Sometimes you can cheat if you have a warm microclimate.

Can I grow a persimmon tree from seed?

If you grow American persimmon from seed, the main thing to remember is that they are “dioecious.” This just means that a plant can be male or female. If you grow a seed and get a male plant, you won’t get fruit from it.

Many commercial varieties produce fruit without a male.

Interested in Forest Gardens?

Here are interviews with forest garden experts.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More Information on Growing Fruit

Articles and Interviews about Growing Fruit

Courses on Fruit for Edible Landscapes and Home Gardens

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

Guide: How to Grow Sorrel (& How to Use it!)

Find out how to grow sorrel, and get ideas for creative sorrel recipes.

By Steven Biggs

Planting Sorrel: An Easy-to-Grow Perennial Vegetable

Sorrel is one of my favourite crops because it checks off a number of important things for me:

It’s easy to grow (it’s a perennial that comes back year after year)

It’s difficult to find fresh sorrel leaves in stores (and if you find them, they’re expensive)

It is versatile in the kitchen (soups, meat, salads, and more)

(And I've cooked with sorrel on TV!)

Sorrel also has a rich herbal history, with a variety of uses.

I’m no herbalist, so in this post I’ll tell you how to grow sorrel and give you lots of ideas for using it in the kitchen.

Haven’t Seen a Sorrel Plant? You’re Not Alone!

Garden sorrel is a hardy perennial.

Sorrel is a familiar ingredient in European cuisine. That’s how it came to North America—with European settlers.

The “wild” sorrel sought after by foragers is simply sorrel that’s escaped cultivation.

Yet many people in North America don’t know to sorrel.

If you’re new to sorrel, it’s grown for its leaves. It’s sour leaves. I think of it as a lemon substitute for northern gardeners.

When I shop at eastern European shops, I see jarred sorrel…horrid sludge. I don’t recommend it. Grow yourself fresh sorrel!

Grow your own sorrel, and skip the brined sorrel!

But it was an eastern European connection that go me growing sorrel. As a teen, I took Ukrainian lessons (hoping to learn my mom’s first language—which she never taught us.) I never did pick up the language—but the teacher, who knew I was a gardener, couldn’t believe I’d never heard of sorrel. And brought me a clump of this plant that she said was an essential ingredient in the old country.

What is Sorrel?

Sorrel is a hardy perennial plant that grows in a clump. It’s tough as nails, hardy into Canadian zone 4.

The long, narrow leaves are ready to pick early in the season, making it one of the first greens to harvest.

You can use the leaves fresh—or cook with them. (See How to Use Sorrel, below.)

Types of Sorrel

There’s more than one type of sorrel. Here are three common ones:

Garden sorrel leaves can be over 30 cm long when plants are in moist, rich soil.

Garden Sorrel (Rumex acetosa). Garden sorrel was brought to north America by European settlers. It's grown in gardens, but is also an escapee that can be found growing wild. Leaves reach 30-60 cm (12-24 inches) long, depending on the growing conditions.

Sheep Sorrel (R. acetosella). Sheep sorrel is another escapee. Sometimes called sourgrass. You might find it filling in exposed spots like vacant lots and roadsides. Seed stalks take on a reddish colour. Spreads by seed and running roots. This is the less-loved cousin to garden sorrel, with smaller, narrower leaves that have a distinct lobe at the base, a bit like an arrowhead. I wouldn’t plant this fast-spreading plant in the garden, but it’s an excellent edible, and popular with foragers.

French Sorrel (R. scutatus). French sorrel is also called round-leaved sorrel. The leaves are shield shaped. Plants are shorter than garden and sheep sorrel.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

How Sorrel Grows

Sorrel grows best in rich, moist soil, in full sun or partial shade. Though that doesn’t mean it won’t grow elsewhere…as evidenced by the behaviour of sheep sorrel in vacant lots!

But in a garden setting, give it water if it’s in a dry location. If it’s in partial shade, you won’t need to water as much.

Flower stalks turn into red-tinged seed spikes. Remove stalks to encourage young leaves—unless you want to collect sorrel seed. If you’ve been diligently removing flower stalks, you’ll be able to continue harvesting for the whole growing season, until the plant shuts down for winter—when the top dies back with fall frosts.

Where to Grow Sorrel Plants

Because sorrel is ready to harvest early, I like to have mine close to the kitchen.

Growing Sorrel in Perennial Borders

As a perennial plant, sorrel is at home in the perennial border. Stick it at the front so it’s easy to reach.

Sorrel in the Vegetable Patch

A row of garden sorrel with seed heads. See the red tinge?

I don’t plant sorrel in my main veggie patch, where I move around crops from year to year. Because it is a perennial plant, I grow sorrel around the periphery, with the rhubarb and asparagus—other perennial vegetables.

I’ve seen an entire row of sorrel plants used as a border in a formal edible garden.

Find out more about perennial vegetables.

Sorrel in the Herb Garden

Garden sorrel and French sorrel are well behaved plants that make a nice addition to a herb garden.

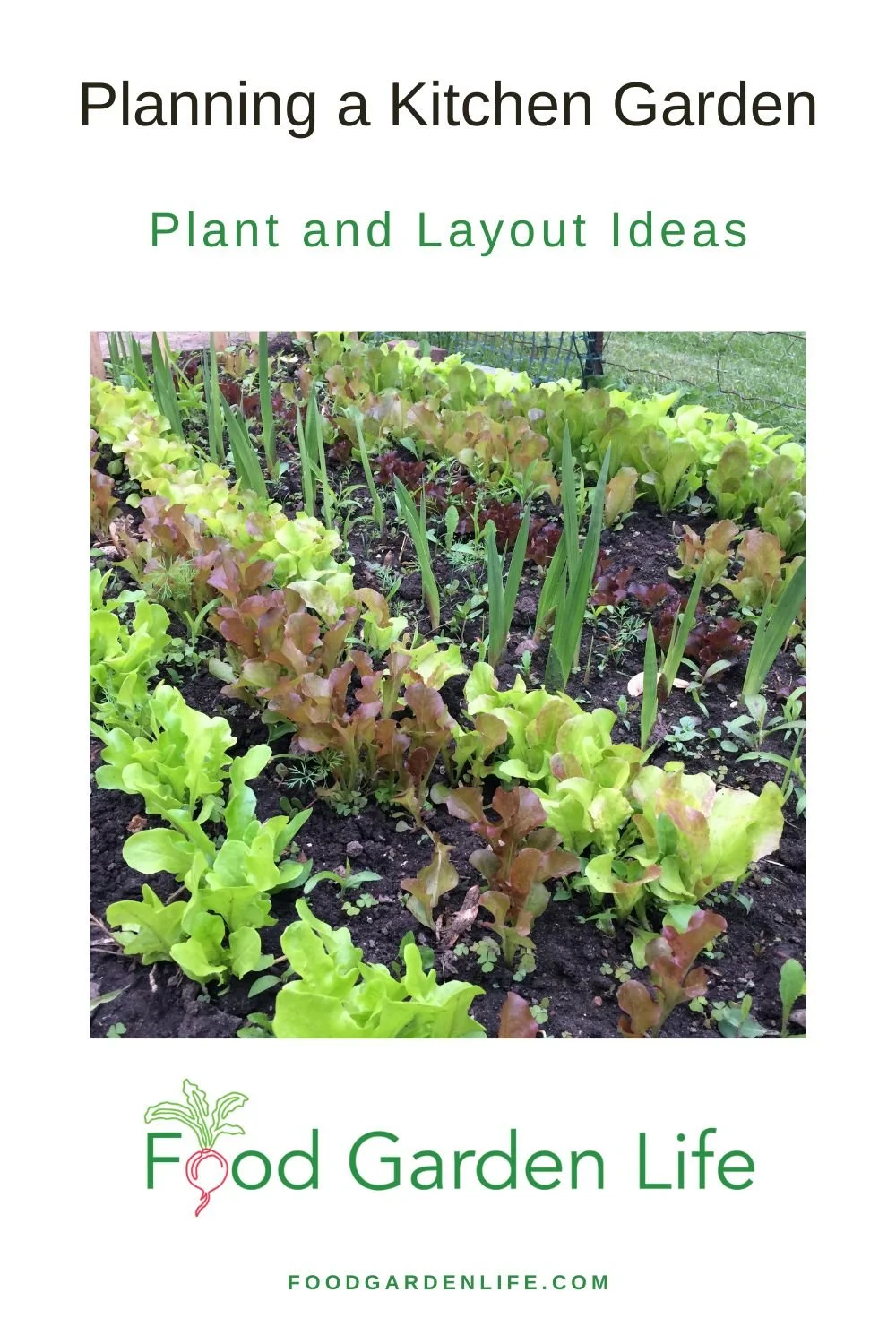

Looking for vegetable garden planning ideas? Here are articles to help you plan and design your vegetable garden.

How to Harvest Sorrel

Young sorrel leaves in the spring are the most tender.

You’ll get the best flavour and texture in spring, from young leaves.

But you can harvest sorrel until fall frosts shut the plant down for winter.

How to Propagate Sorrel

There are two ways to propagate sorrel plants.

Division. When a clump is big enough, divide it in the spring.

Seed. Sow sorrel seeds indoors in early spring. Move to the garden after the risk of frost has passed. Space plants about 30 cm (1 foot) apart in the garden.

FAQ: Sorrel Plants

Will Sorrel Grow in Shade?

Sorrel grows in full sun and partial shade. Because it produces larger, more tender leaves in moist soil, semi-shaded conditions are a good option where conditions are hot.

Are sorrel and hibiscus the same?

An unrelated plant, Hibiscus sabdariffa, also goes by the name sorrel. It’s tangy flowers are used in Caribbean cuisine.

Can I forage for sorrel?

In North America, both garden sorrel and sheep sorrel grow wild.

If you’re interested in foraging, listen to our chat with foraging expert Robert Henderson.

What are oxalates?

Wood sorrel is of no relation to garden sorrel, but it, too, has a sour tasting leaf.

Sorrel contains oxalic acid, a compound also found in spinach and rhubarb. If you go overboard and eat too much, it can cause tummy upset. That means don’t be a pig. You wouldn’t eat a whole bowl of lemons, would you? Consume it with other foods. It’s for flavour—not the main course.

One other thing about oxalic acid is that it can provoke existing joint and kidney problems. So if you have a history of kidney stones, skip the sorrel

What about wood sorrel?

Related in name only, wood sorrels (Oxalis sp.) can be grazed too.

Bloody dock is also known as red-veined sorrel.

Is bloody dock a sorrel?

Bloody dock, R. Sanguineus, is also known as red-veined sorrel. It’s related to sheep, garden, and French sorrel.

But don’t waste a second on it. Unless it’s as an ornamental. (It's quite beautiful.) You’ll find shoe leather that’s more tender than bloody dock leaves.

How to Use Sorrel

Before we get to using sorrel in the kitchen, enjoy sorrel while you’re in the garden. You can graze as you garden. The tangy leaves are refreshing.

Because sorrel is tangy, it pairs well with rich food.

Here are ways to use sorrel:

Use sorrel leaves in salads (I find a sorrel-only salad a bit too tangy, so I mix it with other greens)

Sorrel leaves in sandwiches

Sorrel soup (see recipes below)

In recipes that call for greens such as spinach or lambs quarters, substitute part or all of the greens with sorrel (I add it to my Swiss-chard-and-leek spanakopita)

Add it to sauces for a lemony flavour (I throw in pieces of sorrel leaf when braising meat)

Add sorrel leaf bits to an omelette or frittata

Chop and freeze for use through the winter

I’ve seen a recipe for devilled eggs that includes bacon and sorrel…sounds divine

Gourmet butter: Finely chop sorrel leaves and mix in with soft butter

Making a ranch-style sour-cream or yogurt dip? Add chopped sorrel

Make ordinary pesto shine by adding a bit of sorrel (oh yeah, pairs nicely with blue cheese!)

Sorrel Recipes

Sorrel Soup

Pin this post!

Here’s an easy-to-make sorrel soup recipe.

Ingredients

3 tbsp. butter

1 onion, chopped

3 potatoes, cubed

3 cups sorrel leaves, stem removed

8 cups broth

½ cup sour cream

Salt and pepper to taste

Directions

Fry onion in butter until golden

Add potato, sorrel, broth and simmer (covered) for about 15 minutes, until potatoes are soft

Puree (I use a hand immersion blender)

Whisk in sour cream

Heat to serve (don’t boil)

Sorrel Vichyssoise Soup

If you want to take sorrel soup to the next level—and use some of your homegrown leeks—this take on the creamy potato-leek classic is delicious.

Sorrel vichyssoise soup, topped with a sorrel leaf, a dollop of sour cream, and edible redbud flowers.

Ingredients

2 tbsp. butter

3 cups of sorrel leaves, stem removed

1 large leek, chopped (use both white and pale green parts)

1 onion, chopped

3-4 potatoes, cubed

4 cups water or broth

2 tbsp. salt

4 cups whole milk (use cream if you want something more decadent)

Directions

Fry leek and onion in butter until onion is golden

Add potato, salt, water/broth, sorrel and bring to a boil

Simmer until potatoes are tender

Stir in milk, and then puree

Serve chilled

When serving, I like to float a dollop of sour cream on top, alongside a raft of croutons.

Sorrel Paste and Sorrel Soup

Hear this interview with forager Robert Henderson, who talks about how to make sorrel paste and sorrel soup.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

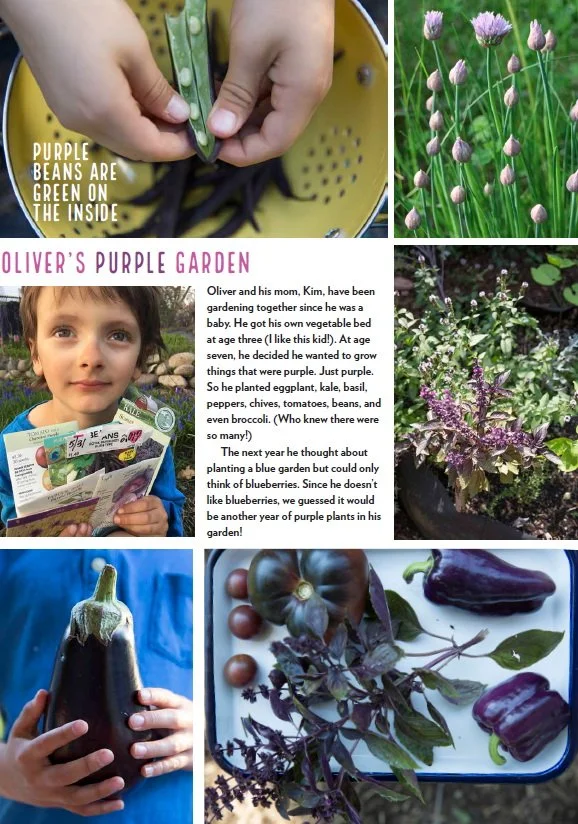

Courses

Edible Garden Makeover. Here’s a course that guides you through creating an edible garden you love. It’s my ode to edible gardening. You’ll find out how to think outside the box and create a special space. Get the information you need about a wide range of edible plants.

Container Vegetable Gardening Masterclass. Here’s a course that gives you everything you need to know for container vegetable gardening success.

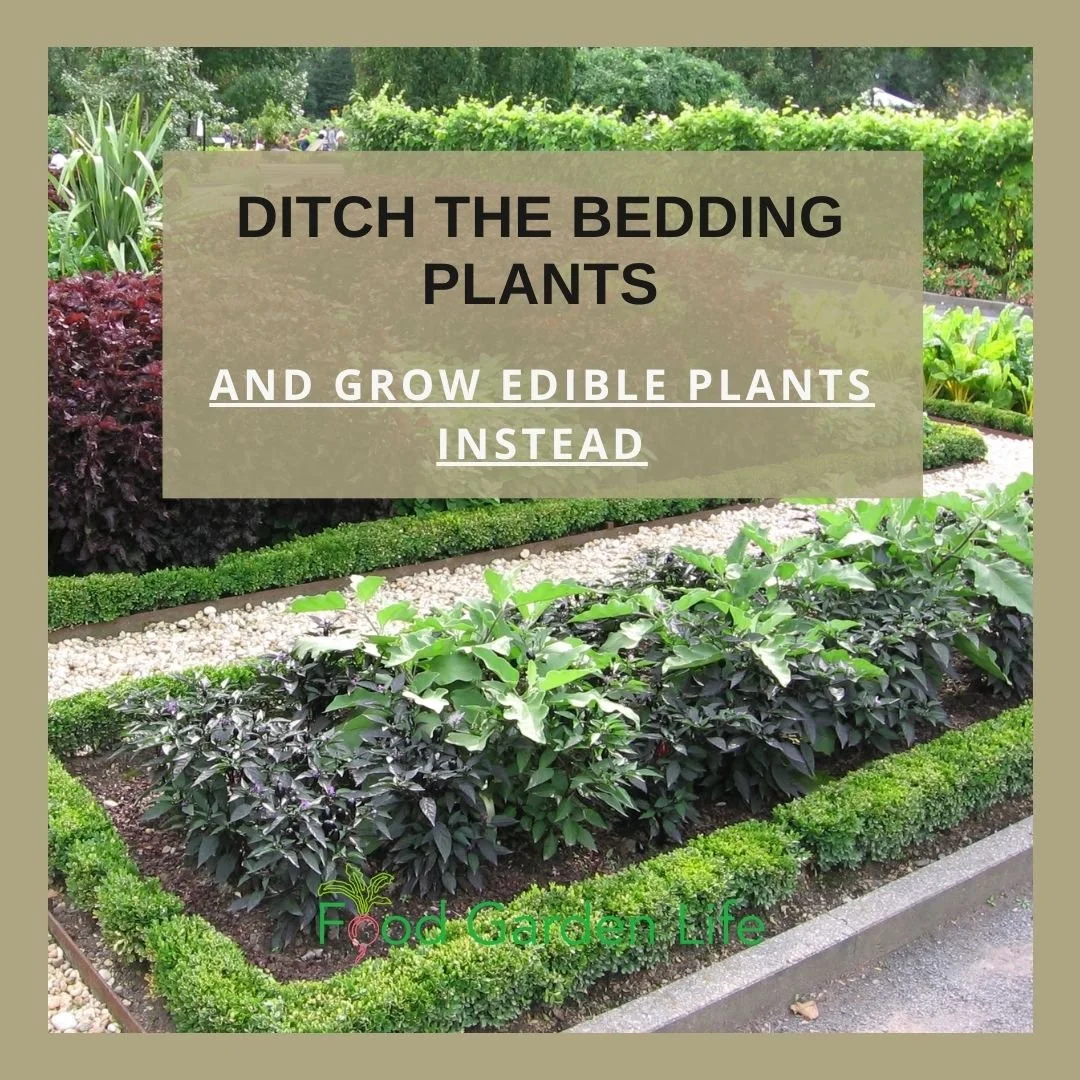

Move Over Bedding Plants...and Try These Edible Garden Plants Instead

Replace some of your bedding plants with edible plants! Find out how to choose suitable crops to use as bedding plants.

by Steven Biggs

A Few Plants for Edible Landscaping

Attractive? Check.

Low maintenance? Check.

Edible? Check.

The peppers were the finishing touch in my front-yard edible landscape. Right by the sidewalk. A nice pop of colour.

What had been my front lawn three months before was an edible front yard—edible plants including salad greens, herbs, vegetables, fruit bushes, and edible flowers.

I was enjoying the mix of colour, height, and texture as I popped one of those peppers into my mouth.

Sound the fire alarm. My face lit up scarlet. I grabbed a basket and, between hiccups, plucked all those hot peppers…worried about hot-pepper misadventures with the school kids that go by twice a day.

So the hot peppers were not a home run.

But with those little scorchers harvested, I left the pepper plants. They had dark green leaves and compact form. Nice bedding plants nonetheless. Just not next to the sidewalk.

If you’re interested in edible plants for edible landscaping, keep reading. This post gives you design ideas and top crops for using as edible bedding plants.

What’s a Bedding Plant?

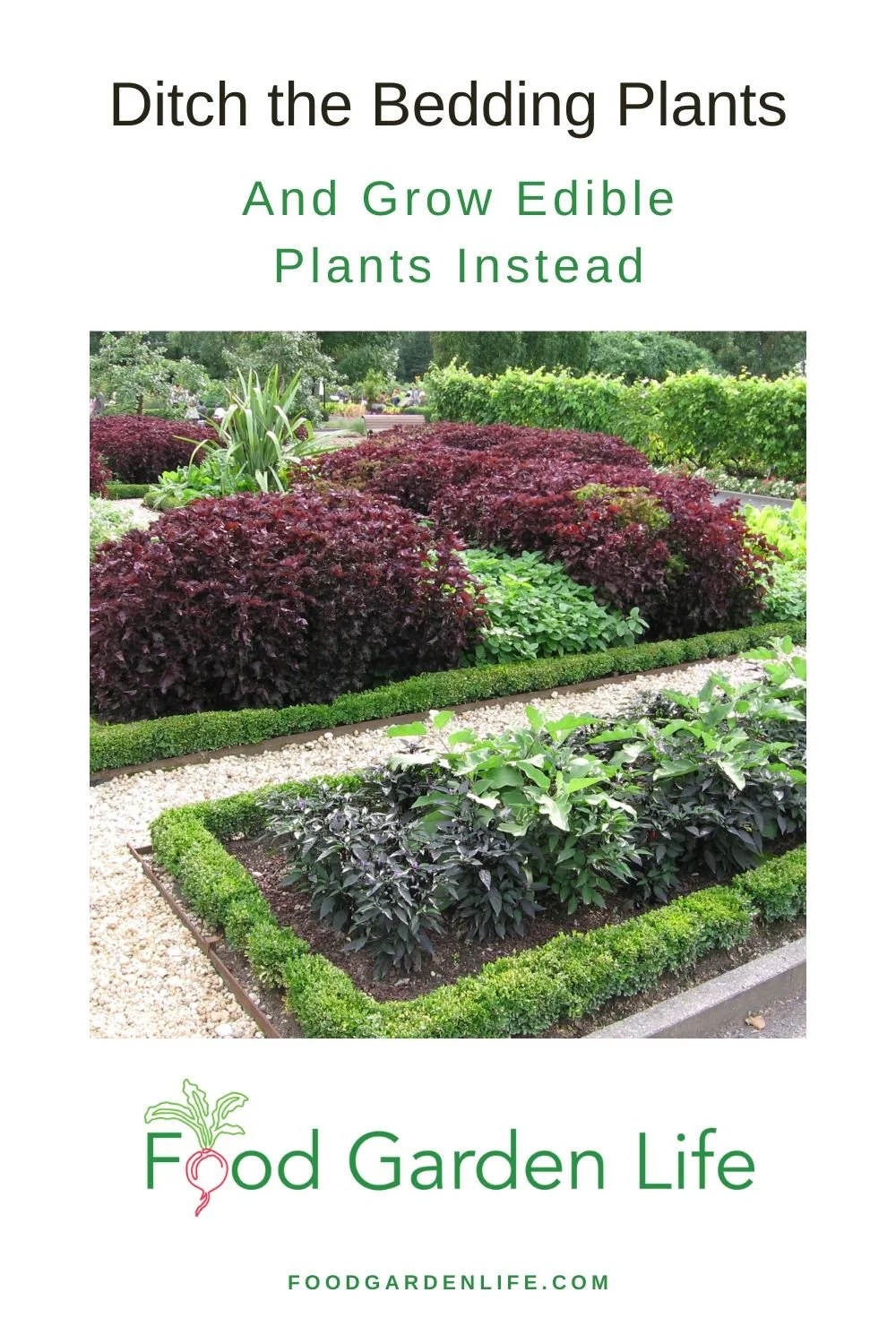

Bedding plants are display plants for seasonal plantings. Here’s a good example, at Butchart Gardens in BC.

Bedding plants are display plants for seasonal plantings. Garden bling. So choices usually combine fast-growing, colour, and resilience.

Some, like coleus, have fabulous foliage. Many have showy flowers. Commonly they’re flowering annuals—though not always. Others, like fuchsia, are tender perennials.

But what they have in common is that they’re typically transplanted into a garden to give an immediate show. Then they’re yanked out at the end of the season.

Lots of common vegetable-garden and herb-garden plants can fit the bill as bedding plants in an edible landscape.

What Makes a Good Bedding Plant?

A good bedding plant is low maintenance. It doesn’t need pruning or staking. You don’t need to hold its hand.

For summertime plantings, a good bedding plant also performs well through the heat of the summer.

Why Use Edible Plants as Bedding Plants?

Using edible plants to make ornamental plantings—instead of traditional bedding plants.

I have nothing against flowers. I go overboard planting flowers every year.

But like many home gardeners, I never have enough space to grow all of the plants I want to grow.

So if I can kill two birds with one stone—edibles for both eating and appearance—count me in. Give me space in the flower garden for some veggies…I'll make it into an edible landscape.

Bedding Plants Through the Seasons

Pin this post!

Most ornamental bedding plants are planted after the last spring frost, but there are exceptions. The most common is pansies—which shine on despite a frost.

(If you didn’t know, pansy flowers are edible!)

You might see plantings of ornamental kale and cabbage in the fall. They soldier on through fall frosts while most bedding plant snivel.

(You can eat ornamental cabbage and kale—though they’re bred for looks, not as gustatory delight.)

Just as plant choice can keep the curtains open longer for a flower garden, choosing the right edible bedding plants keeps an edible landscape looking tip-top into the fall.

Designing Edible Landscapes with Edible Bedding Plants

Swiss chard hanging out with some ornamental bedding plants.

The way you use bedding plants depends on the situation and your taste (sorry about the pun.)

My advice? Be wildly creative and do something that your neighbours aren’t doing. Gardening can be more than practical; it can be creative, too.

(It should be creative, that’s the fun part!)

To get your creative juices going, here are three broad ways of using bedding plants in your edible landscape:

Formal. Think of public display gardens with formal flower beds and symmetrical patterns. (If you’re a detail person, this might be up your alley.)

Informal. This is where you’re getting playful with colour and texture and not constrained by having one big formal flower bed. Like icing on a cake, you “ice” the garden bed…a smear of bedding plants here and there.

Carpet. I once worked at a company where we made the company logo from bedding plants. That’s carpet bedding. We’re talking about a tightly planted, intricate pattern. Like painting with plants.

5 Edible Bedding Plants to Start With

Here are five edible bedding plants you can start with. There are lots more (including the pansies and kale I mentioned above.) But these five edible plants are all work horses, easy to find, and give a good mix of colour and texture.

Swiss Chard. Such an underrated plant. While so many of its leafy-green brethren make haste to flower and die, Swiss chard just grows leaves all summer. And along with green varieties, there are red, orange, yellow—even striped red-and-white varieties. Find out why Swiss chard is also a great choice in the fall garden.

Swiss chard. This underused leafy green makes an excellent bedding plant.

Parsley. The world needs more parsley. Seriously. Beyond garnishing a cheese tray or bulking out your bruschetta mix, parsley is a performer in the edible landscape. Great for edging borders. Planted in larger blocks, curly-leaf parsley is a brush-stroke of texture. And it lasts nicely even as fall frosts fell heat-loving crops.

Parsley. A top-notch bedding plant.

Cardoon. How many edible plants can you describe as elegant? This one has a touch of class. I was riveted when I saw cardoon punctuating the landscape of the historic Spadina House mansion in Toronto. What a bold beauty this plant it! Find out more about cardoon.

Cardoon. An elegant bedding plant!

Basil. From compact, little-leaf varieties to more gangly family members, you can choose from quite a range of plant and leaf sizes. And for leaf colour, remember there’s red and purple, as well as green. The compact basils are great for carpet-style designs. Keep in mind that basil, after a spell of cold fall weather, will quickly pack it in for winter.

Basil. So many choices…here’s a shot from a trial garden.

Eggplant. Compact plant. Attractive flowers. Beautiful fruit. Eggplant can be front and centre in an edible landscape. I love the small-fruited varieties with interesting colours, such as red-fruited eggplant or the skinny striped ones. Eggplant as a bedding plant? I bet your neighbours aren’t doing this!

Eggplant. Even if you don’t love eggplant, you have to admit it’s beautiful!

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

Courses

Here’s a course that guides you through creating an edible garden you love. It’s my ode to edible gardening. You’ll find out how to think outside the box and create a special space. Get the information you need about a wide range of edible plants.

Guide: Growing Raspberries (high yield, NO fuss fruit)

This article explains how to plant and care for raspberries in a home garden.

How to Grow Raspberry Plants

At the back of my aunt and uncle's house was a berm made of heavy yellow sticky clay. It was the soil excavated from an addition to their house. The contractor just dumped soil and rubble at the back of their yard.

And it became their raspberry patch.

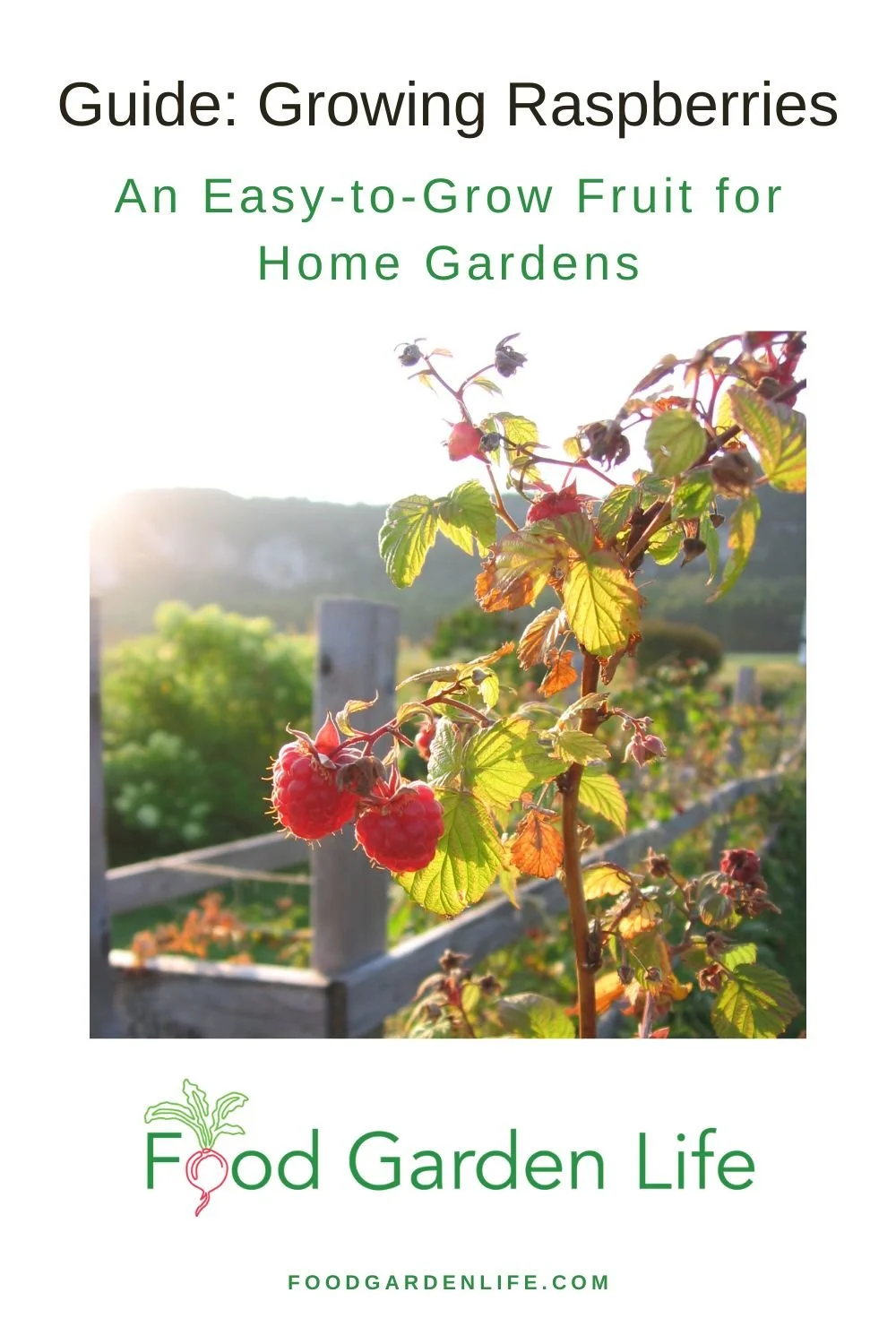

Raspberries are well suited to the home garden because they’ll thrive in imperfect conditions like that hard-packed berm.

A home gardener can take a very systematic approach to raspberry care…or a hands off approach. Both work with raspberries. (Though by investing some time, you increase the harvest.)

If you want to find out how to grow raspberries, get ideas for using them in the landscape, and find out top tips for raspberry care, keep reading. This post tells you how.

Primer for Growing Raspberries

Let’s start with some raspberry basics.

How Raspberries Grow

A raspberry plant has perennial roots, but the canes live for only two years.

Raspberry bushes have perennial roots (meaning it lives for many years) but the tops—called the “canes”—live for only two seasons.

First-year canes are called “primocanes.” They start out green and tender, and get brown and woody as the season progresses.

Second-year canes are called “floricanes.” Floricanes flower and produce fruit, and then die at the end of the season.

Raspberries that produce fruit on the floricanes are called summer-bearing raspberries or summer-fruiting raspberries.

But some varieties of red and yellow raspberries grow a later crop of fruit on primocanes. These are called everbearing raspberries, fall-bearing raspberries, autumn-fruiting raspberries, or primocane raspberries.

Raspberry Fruiting

Raspberries are late to flower, so flowers are not likely to be hit by late frosts.

You don’t need multiple varieties to get fruit because raspberries are self-fertile. You will get fruit even if you have only one plant.

Here’s when raspberry fruit ripens:

Fruit on floricane-fruiting varieties ripens early summer through to midsummer.

Fruit on fall-bearing varieties ripens mid to late summer. If winter is slow to arrive, you can harvest raspberries until there’s a heavy frost.

Raspberry Growth by Fruit Colour

Yellow raspberries are the same species are red raspberries.

There are red, yellow, black, and purple raspberries. The red raspberries and yellow raspberries are the same species. Black raspberries are a different species. And purple raspberries are a hybrid of red and black.

Red and Yellow Raspberries

Red raspberry and yellow raspberry plants send up new canes from the base of existing canes. New canes also grow from the roots. That means that they don’t remain in a clump, and plants spread out in all directions.

Black and Purple Raspberries

These grow in a tidy clump, with new shoots growing from the base of the clump.

Where to Plant Raspberries

Black raspberries.

If you want to grow raspberries by the book, look for full sun and a rich, well-drained soil.

But in a home garden setting, we don’t always have the ideal conditions that a market gardener might have.

You don’t have to give raspberries the prime real estate.

They grow in a wide range of soils. Very sandy or very heavy clay are the least ideal—both situations can be helped by adding lots of organic matter. The ideal pH is around 6, though they can do fine on many soils.

They don’t do well in soil that’s continually wet. So avoid wet locations. Or, if you only have a wet location, consider raised beds.

Raspberries are affected by a disease called verticillium wilt. There are a few common plants that we grow in home vegetable gardens that also get verticilium wilt: the nightshades (tomato, eggplant, pepper, potato) and strawberries. If you've been growing these and you've had wilting and dieback, this is a red flag. Put your raspberries in another part of the yard.

Planting Raspberries

Purple raspberries.

A raspberry patch can last many years. So set it up right.

Your first step is to get the soil in good shape by adding lots of compost.

Next, make sure there are no perennial weeds.

Raspberry Spacing

How you space raspberry plants depends on how you’re fitting them into your yard. However you do it, though, your red and yellow raspberries will fill in the spaces soon enough.

Rows Make Picking Easier

Raspberries are easier to pick when you grow them in rows. If they’re in a patch, you have to blaze a trail for picking…and that might mean scratched arms!

I like rows that are at least 60 cm (2’) wide. Wider than that and they’re more difficult to pick. Leave 60-90 cm (2-3’) between plants. Because black and purple raspberries have long, arching canes, you can space them a bit farther apart.

Raspberry Hedge

Your neighbours might take issue with me for mentioning this…but what about a raspberry hedge as a way to separate yards? Because they sucker, a raspberry hedge creeps outward—so be prepared to rein it in.

Raspberries in the Home Landscape

Beyond rows or hedges, wherever you plant them, keep in mind that raspberries spread.

This is a plant that’s perfect in a spot with natural boundaries—like a space framed by a house and a patio.

In the wild, raspberries often grow in partial shade, at the forest edge. Think of this if you’re creating a layered landscape or a food forest.

I’ve seen commercial raspberry production in high tunnels, both in the ground and in pots. This is more work than most home gardeners want, but it gives the gardener more control of conditions, meaning the chance to boost yield. It also extends the fall harvest window.

Raspberry Care

Weeding

In an established raspberry patch it’s difficult to remove perennial weeds like thistle or bindweed. So don’t let them get established!

Raspberries have shallow roots, so don’t deeply cultivate the patch. You can scuff the surface or spot-dig bigger weeds.

Even better, minimize weeding by mulching your raspberry patch. This also helps to hold in moisture.

Trellising

Trellising raspberry plants with a T at either end of the row, and wires strung in between.

A simple way to support raspberry canes in rows is to have a horizontal wire running the length of the row on either side of it. To do this, install posts at the end of the row and put pieces of wood across the posts, so they’re T-shaped. Then run wires from one T to the other. The wire can be 1 – 1.5 metres off the ground—depending on how tall your canes are (which depends on the variety and the growing conditions.)

In short, you’re just getting canes to grow between horizontal wires, which prevent them from leaning too far away from the row.

A variation for those growing a skinny row of raspberries is to have a single wire down the centre, and then tie each cane to it.

Note: Fall-bearing types can get tall and top heavy when laden with fruit. If so, trellising help keep canes upright.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Pruning Raspberries

If you let every cane grow, you’ll have smaller fruit. If you thin out canes, those remaining give more—and bigger—fruit.

If you’re managing your raspberries more intensively, you might opt to prune twice a year, with summer pruning and dormant pruning. You’ll still get raspberries if you don’t prune, but you can optimize production (and have a nicer looking patch) with regular pruning.

Summer Pruning

Prune out weak primocanes. Thicker, more vigorous canes give more fruit.

I aim for 30 cm (12”) between primocanes, bearing in mind that in a wide row there can be more than 1 cane in a 30 cm (12”) span.

Pinch tips of new black and purple raspberry canes mid-summer to encourage side branching.

After floricanes finish fruiting, cut them out (you can also just wait to do this later, while the plant is dormant).

Dormant Pruning

These floricanes will be pruned out at the end of the growing season.

I prune in the fall. In colder climates, prune late winter or early spring pruning so winter dieback can be removed with pruning.

Prune red (and yellow) raspberries back to 1.2-1.5 metres (4-5’) high before growth begins. This encourages more side shoots…meaning more fruit.

Cut back side branches on black and purple raspberries by half before growth begins in the spring.

Here’s an Idea: If you have fall-bearing raspberries and want only the fall crop, cut all of the canes to the ground in the spring before growth begins.

Water

Water raspberries during dry conditions to prevent dry, seedy fruit.

Raspberry Varieties

Here are things to think about as you choose raspberry varieties:

Hardiness

Summer or fall bearing

Taste

For summer varieties, there are early-, mid-, and late-season varieties

When it comes to varieties, it’s worth doing your homework to see which varieties are recommended for your area. Hardiness varies between varieties. Taste varies quite a bit too—so as you’re looking at zone ratings, see how the flavour is rated.

If you have a short growing season, there might not be enough time for fall-bearing raspberries to ripen. That’s because ripening stops and plants start to shut down with the first hard frost. To find out more about taste and what varieties do well in your area, ask other gardeners—or check in with a nearby pick-your-own farm.

In areas with winter thaws followed by extreme cold, where winter dieback is a concern, an early-fruiting primocane raspberry has the advantage of not relying on overwintering canes

Black raspberries not as cold hardy as red and yellow raspberries.

Challenges

Competition

My main competition for berries is my kids. But for many gardeners, it’s birds. Because canes are fairly low, netting, or growing in a net tunnel, are options.

Decline

A raspberry patch usually goes into decline after a few years. Start a new patch, on another piece of ground.

Raspberry Propagation

Use a spade to divide clumps in the fall, or in the spring before new growth begins. Spring and fall are also the time to dig up wayward suckers from red and yellow rapsberries.

Black and purple raspberries can also be propagated by tip layering. Here’s an explanation of tip layering for blackberries; it’s the same process for purple and black raspberries.

Buy Raspberry Canes

Many garden centres sell potted raspberry plants. The advantage to container-grown plants is that the planting window is much wider. But they cost much more than bare-root plants.

Dormant bare root plants, with roots washed of soil, are shipped in late winter and spring. These are available from many online nurseries—and the price per plant is considerably cheaper than potted plants.

FAQ – Grow Raspberries

Pin this post!

Do raspberries grow in shade?

They tolerate partial shade well, though the yield is less than in full sun. My productive black raspberry patch gets only a half day of sun.

Does frost affect raspberry flowers?

It can, but because the flowers are late to open, it’s rarely a problem.

I want to renew my raspberry patch with new plants. Can I put it where my current patch is?

It’s better to choose a fresh piece of ground, if that’s an option. That’s because raspberries planted where there were recently raspberries growing might not do as well. If your old patch had disease, it can affect the new plants.

Why does my raspberry fruit crumble?

If the ripe berries crumbles when you pick them, the problem might be poor pollination. This can happen when the weather at the time of bloom is rainy or overcast.

Can raspberries grow in a pot?

Yes. Raspberries grow well in containers. As with any container-grown crop, success depends on providing a large enough container, and sufficient water and feed.

More on Raspberry Plants

And here’s more on how to tip-layer blackberries and black raspberries.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More on Fruit Crops

Articles: Grow Fruit

Visit the Grow Fruit home page for more articles about growing fruit.

Here are a few popular articles:

Courses: Grow Fruit

Here are self-paced online courses to help you grow fruit in your home garden.

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

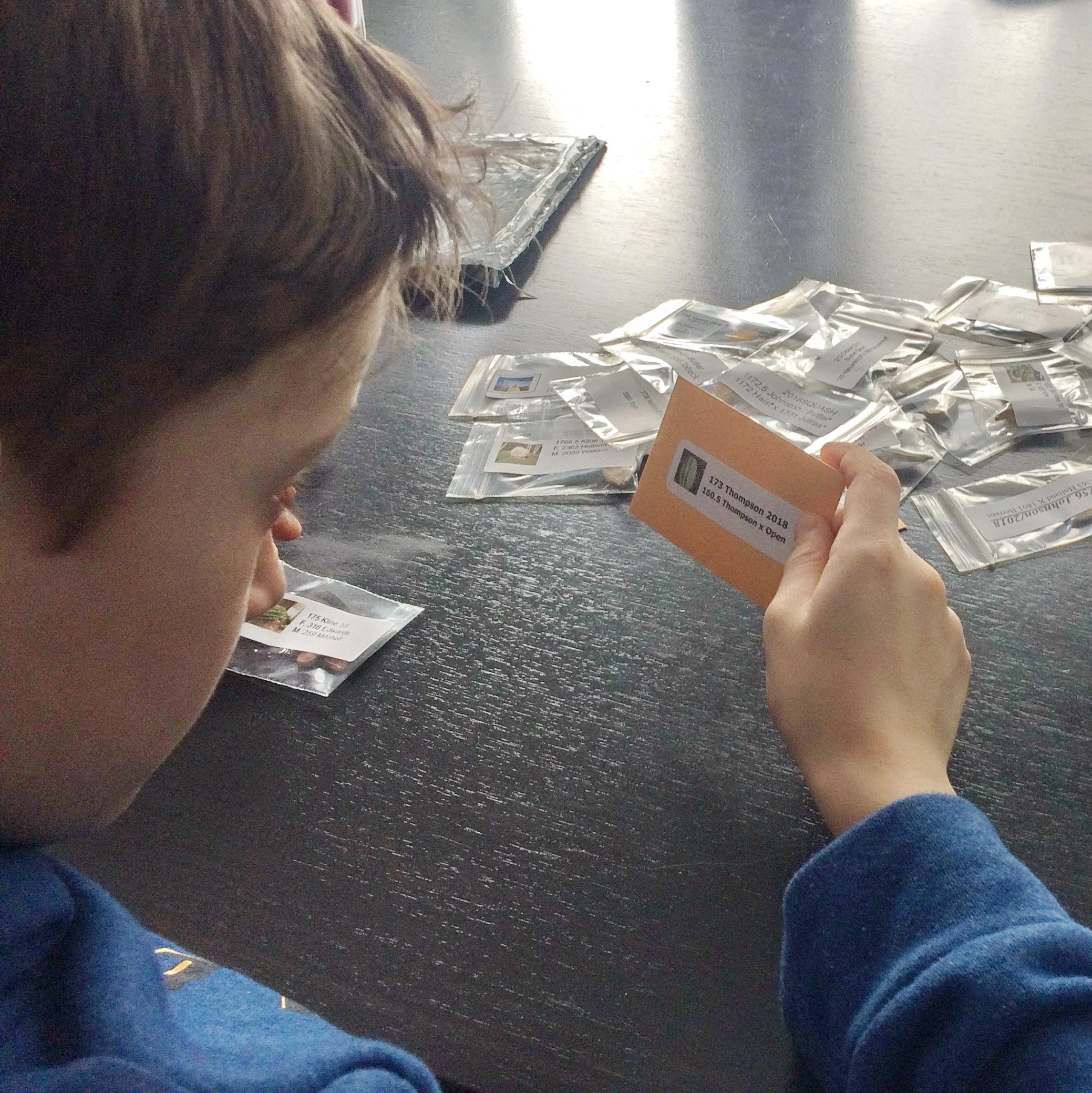

Seed Shopping Smarts: Know The Lingo So You Can Get The Best Seeds

What’s your seed-shopping vocabulary like? Brush up on your seed lingo in this glossary of seed terminology so you can choose the best seeds for your needs.

By Steven Biggs

Best Seeds for Your Needs When You Know The Lingo

Get the best seeds for you needs when you know seed terminology.

When I worked at a marketing and communications company, there was a linguistic divide in our office.

The in-house application developers had a vocabulary that was incomprehensible to those of us working the phones.

As an outsider who wasn’t too tech savvy, it took me a while to absorb the new vocabulary.

Specialized Seed Vocabulary

It’s easy to feel like an outsider when you encounter specialized lingo. And it’s not just in the tech sector. (My father-in-law doesn’t realize I miss most of what he’s telling me when he shows me under the hood of his car…and now I have a son who has a whole vocabulary around mountain biking!)

Gardening has specialized vocabulary too. And I’ll be glad if you find this this glossary of seed terminology helpful in choosing the best seeds for your garden.

Glossary of Seed Terminology

Here are common terms that you’ll find when you seed shop. Knowing what they mean will help you get the best seeds for your situation.

This glossary of seed terminology will explain important seed vocabulary.

Annual

An annual plant has a one-year life cycle. It flowers, makes seed, and dies in one year. Common annuals include veggies such as beans, lettuce, and spinach.

(To confuse things, some of the so-called annuals that we grow in northern gardens live more than one year in warmer climates—but die in our cold winters, so we treat them as annuals. But actually, they’re not. A good example is fuchsia.)

Biennial

A biennial has a two-year life cycle. The first year, it makes leaves; and in the second year, flowers and forms seeds. In the veggie garden, a number of common crops are biennials, but we usually harvest from them during the first year and then remove them. Unless we’re saving seeds. Parsley, Swiss chard, and carrots are biennials.

Botanical Name (Scientific Name, Latin Name)

This is the official two-part name, often italicized. Useful when we want to make sure there’s no confusion around what plant we’re dealing with.

Common Name

This is the everyday, plain English name. The only problem is that sometimes the same name gets used on more than one plant. Bluebell is a good example. That’s why, when in doubt, you can check the Botanical Name to make sure you’re ordering what you want.

Cotyledon

This is the name of the first leaves that emerge when a seed germinates. You might see this word when seed shopping because transplanting guides often talk about “seed leaves” or “cotyledon leaves” when explaining when to transplant your seedlings. They look different from the “true” leaves that come afterwards.

Many common garden crops are biennials. Parsnip (seeds at the top) is a good example of a biennial in the vegetable garden.

Cultivar

This word comes from “cultivated variety.” It just means a variety intentionally grown by humans. People often use this term interchangeably with “variety” although there are also naturally occurring plant varieties—which is why the distinction. If you see a name between single quotes (‘ ‘) it’s likely a cultivar name. A cultivar can be an open-pollinated or a hybrid (see below).

Days to Maturity (Days to Harvest)

An approximate number of days until harvest. This number is always approximate because many things (weather, growing conditions, the stage of harvest) have an effect on it.

For crops we plant directly in the garden, it’s the number of days from seeding until harvest; while for crops we start indoors as transplants (e.g. tomatoes) it the number of days from transplanting in the garden until harvest.

Dioecious

Dioecious plants have male and female flowers on separate plants. In the veggie garden, asparagus is an example of a dioecious plant.

Direct Sow (Direct Seed)

Pea seeds, an example of a crop that we usually direct sow.

This is when we plant seeds in their final, outdoor destination. Crops that are commonly direct seeded include carrots, beets, beans, and peas.

Germination Rate

Seed companies test germination. (At least I hope they do!) If you see a percentage on a seed packet, it indicates the germination rate from a germination test—and this should give you an idea of what sort of germination you can expect at home under good conditions.

GMO (Genetically Modified Organism)

Many people understand this to mean a plant into which genetic material from another plant or life form is inserted. What’s confusing is that the way this term is often understood and the official definitions differ.

The exact definition depends on who you ask and where you are. Here’s the official definition used by the Government of Canada.

“A genetically modified (GM) food is a food that comes from an organism (plant, animal or microorganism) that has had 1 or more of its characteristics changed on purpose. Organisms can be modified by different processes, including: conventional breeding techniques, like cross-breeding or mutagenesis (a change in the genetic make-up of an organism caused by chemicals or radiation); modern biotechnology techniques, such as genetic engineering; gene editing.”

Here’s what can be confusing: The wordy definition above includes traditional breeding…the sort of breeding that might have given us some of our heirloom varieties. What many people want to avoid is “genetically engineered” seeds. Genetically engineered seeds are mostly found in commodity crops (think canola and corn) – and are not sold to home gardeners.

Harden Off

When seedlings are moved from protected conditions such as indoor grow lights or a greenhouse, they are “hardened off,” which means they are gradually acclimated to the brighter light, different temperatures, and wind outdoors.

Hardy Annual

An annual that tolerates some frost and cool conditions. For example, a common hardy annual vegetable is arugula—which, if you let it make seed, you’re likely to find growing up on its own in your garden while there are still cool conditions.

Heirloom

Like the word “natural” in the health food sector, “heirloom” is one of those fuzzy, poorly defined words that marketers adore. There’s no precise meaning. But, in general, it means an older open-pollinated variety.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Hybrid Seeds

Hybrid seeds result from cross-pollinating two varieties with desirable traits. In the seed industry, it’s done in controlled conditions, so there’s no chance of an errant pollen grain giving something different.

Hybrid seeds tend to be more expensive because of the labour needed to make the cross. Hybrids are often made to have desirable traits such as disease resistance and vigour…and they’re also made because it’s an industry.

If you see the term “F1,” that refers to the first generation of seed after the cross. That’s usually what’s for sale at seed vendors. When you save seeds from a hybrid plant, it will probably be different from the parent plant.

Hybrids occur in nature too, but the hybrid seeds you find at vendors will have been deliberate. When people are new to seed shopping they sometimes wonder if hybrid has something to do with genetic engineering—and it doesn’t. It’s entirely different.

Last Frost Date (Average Last Frost Date)

The date in the spring when—on average—there isn’t any more frost in your area. It’s figured out using historical weather data.

This date is like a marker post for seed sowing. When a seed catalogue recommends starting tomato seeds 8 weeks before your average last frost date, this is what it’s referring to.

This date is also used when deciding when to move seedlings into the garden. (But remember…an average last frost date means that some years there is frost after that date.)

Monoecious

Monoecious plants have both male and female flowers on the same plant. Melons are monoecious; and if you look closely, you’ll see some of the flowers have little melons-in-waiting next to the female flowers, while the male flowers have none.

Open Pollinated (OP)

Open-pollinated bean varieties are easy to save seeds from because there is not usually much cross-pollination with other varieties.

Open-pollinated varieties are stable varieties that you can save seed from and get plants that are like the parent plants. Some open-pollinated varieties are heirlooms; some are recent.

Note: To get seeds like the parent plant, there can’t be “cross-pollination” with other varieties. Some types of plants mostly self-pollinate (they have perfect flowers, see below), so you’re likely to get seeds like the parent plant without doing anything special. But some plants have separate male and female flowers—meaning insects might pollinate them with pollen from another variety. Squash is a good example. In that case, open-pollinated varieties are grown in isolation when saving seed.

Organic

Generally understood to mean that the plants the seeds come from are not treated with synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. The thing to keep in mind when seed shopping (food shopping, too, actually) is that there are organic certification bodies—agencies that make sure a producer adheres to a set of standards. So you might come across seed that a seller says is organic—but is not “certified” organic.

Parthenocarpic

This refers to varieties that can make fruit without pollination. The resulting fruit has no seeds. You’re most likely to see this term as you browse cucumber varieties.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Pelleted

Sometimes small or irregularly shaped seeds are coated with clay to make them easier to handle or dispense with seeding equipment. These “pelleted” seeds are usually more expensive.

Perennial

A plant with a life cycle spanning a number of years.

Perfect Flower

A flower that has both male and female parts.

Set

Onion “sets” are small, pre-grown onion bulbs that you can plant directly in the garden instead of growing onion seedlings. It’s a great option if you don’t have a lot of indoor space for growing onion transplants.

Tender Annual

An annual plant that does not tolerate frost. We usually start tender annuals indoors, in warm conditions, and then transplant them outdoors when there is no further risk of frost. A good example of a tender annual is basil…which quickly wilts in protest in cool weather.

Transplant

Tomato seedlings, or “transplants.” We use the word transplant as both a noun and a verb.

The word we sometimes use to refer to the little seedlings that we start indoors. Of course, it’s also the act of replanting—transplanting—the little seedings. So both a noun and a verb!

Treated Seed

If you’ve ever seen a pink pea or bean seed, it’s been treated with a fungicide. That treatment is done to prevent rot in cold, wet soil. If you don’t want seed that’s treated, look for “untreated” seed.

Untreated Seed

Seed that has not been treated.

Crop-Specific Lingo

Beans

Pin this post!

Bush bean plants are shorter, and tend to have an earlier and briefer period of harvest. Depending on the variety, they might or might not need support.

Pole and runner beans get quite tall, and will need support. The harvest is later, and the harvest period is longer.

Peas

Vining pea varieties, like runner and pole beans, get quite tall and have a longer harvest window.

Squash

Bush squash are compact (at least for a squash plant!).

Vining (running) squash have long stems that spread far and wide.

Tomato

Determinate (bush, patio) tomato plants get to a certain size and then stop growing. They are relatively compact, and flower and fruit in a shorter time. Even thought they are compact, they are not self supporting—so if you like your tomato plants off the ground, use a stake or a cage.

Indeterminate (vining) tomato plants keep growing and making fruit as long as conditions permit. They get very tall if the growing season permits. (This is the sort of tomato used in greenhouse tomato production here in Ontario: Plants are grown up twine, and as they get taller and taller, the twine is lowered and the base of the stem is coiled on the ground.)

There are also semi-determinate tomato varieties.

Dwarf tomatoes are very compact, making them a good choice for growing in planters. They often grow 60 - 120 cm tall (2-4’)

Micro-dwarf tomato plants are tiny, only 15-30 cm (6-12”) tall. Perfect for a window box. Just adjust your yield expectations accordingly with such a small plant.

Find Out about Seed Shopping in this Podcast

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More on Vegetable Seeds

More on Growing Vegetables

Vegetable Gardening Articles

Vegetable Gardening Courses

Edible Flowers: Flowers You Can Eat (AND how to use them)

Edible flowers: Find out which flowers are edible—and how to use them to spice up your cooking and culinary creations.

Edible Flowers for Your Garden

Bee balm (bergamot) is an edible flower that’s a good fit for a perennial border.

When I taught at a college with a farm-to-table horticulture and culinary program, the chef asked us to harvest small zucchinis with the flower still attached at the end. A pedestrian ingredient elevated to gourmet.

Yet they often fly under the radar. You can fit edible flowers into a vegetable garden, herb garden, edible landscape, and beyond. You might have some growing there already.

Once they’re on your radar, you’ll see them everywhere.

If you’re wondering what flowers you can eat, keep reading. This post explains where you can grow them, lists easy-to-grow edible flowers, and has ideas for creative ways of using them.

How to Grow Edible Flowers

Use bachelor’s buttons petals to decorate a cake, or dried in a tea.

Because edible flowers grow on a very wide range of plants, there’s no one-size-fits-all growing advice. Many are sun loving. Some tolerate some shade. While many are annuals, there are shrubs and trees too.

Success growing edible flowers is a matter of selecting the right plant for the right growing conditions.

Some of my favourite edible flowers are the ones that self-seed in my garden, meaning they come back year after year without me having to plant them. I like gardening that way.

NOTE: Not all flowers are edible. So don’t eat it if you’re not certain it’s edible. Start with small amounts if it’s the first time you’re eating a flower. As with any food, some people can have sensitivities.

Calendula (pot marigold) self-seeds in my garden. I let a “hedge” of calendula frame one of my potager beds.

Where to Grow Edible Flowers

Edible Flowers in the Vegetable Garden

There are lots of edible flowers to be found in a vegetable garden.

Here are some of my favourites.

Arugula flowers are edible and have a peppery taste similar to the leaves.

Arugula. Like the leaves, these small flowers are peppery. They’re nice atop a salad or a savoury soup.

Broccoli. We grow broccoli to harvest before the flowers open…but if your broccoli beats you to the punch and the flowers open, you’ll have cheery yellow flowers to toss into a salad or use as a garnish.

Fennel. Clusters of small, bright yellow flowers have a delicate anise flavour. I’ve seen a chef tap fennel flowers over a white plate to decorate it with the brightly coloured pollen. Along with Florence fennel, there’s bronze fennel, a short-lived perennial in my garden zone (and an invasive in others…). Find out more about bronze fennel and other edible perennials.

Pea. Flowers taste like…peas. As well as the flowers, you can also eat young shoots and tendrils. Caution: Flowers of peas we grow as a vegetable (Pisum sativum) are edible; flowers of sweet pea (Lathyrus odoratus), grown as a cut flower, are poisonous.

This squash flower is calling out for a wedge of cheese, some batter, and a bath in the deep fryer!

Runner bean. Along with edible flowers, runner bean flowers have long enough stems to make excellent cut flowers. In my garden, they’re a magnet for hummingbirds too! Runner beans are also a top crop for vertical gardening: Find out more about vertical gardening.

Squash. Slightly sweet taste. Stuff whole flowers with a wedge of cheese and batter and deep fry. Or, slice and serve atop a bowl of soup for a dash of bright yellow or throw into a stir fry just before serving.

All of these veggies can thrive in container gardens. I teach people how to grow great container vegetable gardens in my this masterclass.

Edible Flowers in a Potager or Kitchen Garden

I like to think of potager gardens as grazing gardens: Instead of large quantities of each crop for preserving, we’re growing smaller quantities to pick and eat fresh on an ongoing basis. I like a grazing garden with lots of annual flowers in it for cutting…and eating.

Bachelor’s Buttons. Flowers come in blue, pink, and white. Eat fresh, or dry to add colour to your home-made tea blends. Or sprinkle some petals over the bowl of whipping cream you’re putting out for dessert.

Calendula petals are a homegrown saffron substitute, great for colouring rice.

Calendula. Great for colour, though not a lot of flavour. Pluck off the petals to add to salads or dress up a plate. Use dried petals to add colour to rice dishes—a homegrown saffron substitute.

Rose. Pluck some rose petals to chop and add to a fruit salad. The lower, white portion of the petal can be bitter, so before using them, do a taste test—and remove the white portion if needed. Edible flower expert Denise Schreiber recommends rose-petal ice cream.

Sunflower. Use these brightly coloured and mildly bitter petals as a cheerful garnish.

Edible Flowers for Containers and Container Gardens

You can eat the whole nasturtium flower. It has a peppery taste, like the leaves.

Many well-known edible flowers are grown as annuals, and many are well suited to growing in containers.

Here are a couple of my favourites.

Begonia. Tuberous begonia petals have a citrusy taste and a firm texture.

Nasturtium. Unlike some flowers, where you must first remove petals from a corky core, you can pop a whole nasturtium flower into your mouth. Like the leaves, the flowers have a peppery flavour. (See below…rinsing before eating can be a good idea!)

Edible Flowers for an Edible Landscape

Here are ideas for perennials, shrubs, and trees with flowers you can eat for an edible landscape.

Apple blossoms have a floral flavour.

Apple. These blossoms have a floral flavour.

Bee Balm. A.k.a. monarda, pluck these slightly spicy petals to dry for tea or use fresh tossed into a fruit salad.

Daylily. Use the flower bud in stir fries instead of snap peas. Dice the flowers to throw into frittatas and pancakes. Or…what about an open flower to hold a scoop of ice cream—instead of an ice cream cone!

Elderberry. Use these sweet-smelling flowers fresh in fritters. Dry them for tea. Or to make cordial or elderflower champagne. Don’t graze on raw elderflower—this is a flower that should first be processed.

Redbud flowers taste sweet.

Lilac. Sweet, with a little drop of nectar in the throat. When I was a kid we’d pluck these from my parents’ hedge and suck on them to extract the sweet nectar.

Linden. Dried linden flowers make a lovely tea. My Aunt Anna had me pick them for her from the lindens that lined the front of her apartment building.

Eastern Redbud. Sweet little pink flowers that are out early in the season.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Edible Flowers in a Herb Garden

Basil. The flowers taste like the leaves. I pluck off these wee flowers to sprinkle over a salad or a bowl of tomato soup.

Borage flowers taste a bit like cucumber.

Borage. The sky-blue colour of borage flowers is a visual delight in the garden. Float these cucumber-flavoured flowers in a pitcher of water. This is a plant that reliably self-seeds in my garden.

Chive. Pull apart the flower heads and then sprinkle these onion-flavoured flowers over a curry!

Cilantro. This herb always flowers more quickly than I want…and as it flowers, it stops growing new leaves. But all is not lost, because the flowers, too, are edible.

Dill. Like fennel, these heads of small, yellow flowers are edible. I use a whole dill stem with leaves and flowers when I make a crock of dill pickles.

Garlic Chive. Use in the same way you do chive flowers. They look nice when you float them in a bowl of water.

Lavender. Float lavender flowers in a summery drink. One of the most unusual—and delightful—ice creams I ever had was a lavender-flower ice cream.

Lemon flowers have a very sweet smell and taste.

Lemon. I wasn’t sure where to put lemon in this post, so I’ve included it with herbs, since the leaves are used much like bay leaves. The flowers have a sweet smell and taste. Dot them on the thick whipped cream you spread over a summery fruit flan. Find out how to cook with lemon leaves.

Here’s a course about how to grow lemons in a cold climate.

Lemon Balm. The flowers have the same lemony taste and smell as the leaves. Eat as many flowers as you can, because this is one plant that’s quite naughty when it comes to self-seeding everywhere.

Mint. Shunned by many gardeners for its aggressive ways, mint flowers are a nice touch with something sweet…I’m thinking blueberry compote. (If you’re worried about mint taking over your garden, just grow it in a pot. That’s what we did when my daughter came home with 19 types of mint.)

Oregano. I love oregano with anything tomato. Or, how about a herb butter dotted with oregano flowers.

Rosemary. Like the leaves, the beautiful blue flowers have a resinous, unmistakable taste.

Edible Flowers…in the Lawn!

Chamomile. Apple-like smell. Use dried for tea, or fresh to adorn a plate. This herb is quite tolerant of being shorn like a sheep, making a chamomile lawn an unusual option.

Dandelion. I don’t know many gardeners who set out to grow dandelions, but they usually invite themselves to your lawn anyway. I harvest dandelion leaves and flowers from my lawn every spring. Pick when young, as they become more bitter when older. Pluck the petals from the centre of the flower before using.

Thyme. Like chamomile, here’s another herb that’s useful to create a lawn. When choosing a thyme variety for your edible-flower lawn, keep in mind that some types of thyme are low and creeping, while others are more upright and woody, making them less suited to using for a lawn.

Sweet Woodruff. The small, white flowers combine sweetness and vanilla. I also love the glossy, dark green leaves.

How to Harvest Edible Flowers

Pin this post!

When to Pick Edible Flowers

Pick flowers as close to when you’ll use them as possible for the best colour and flavour.

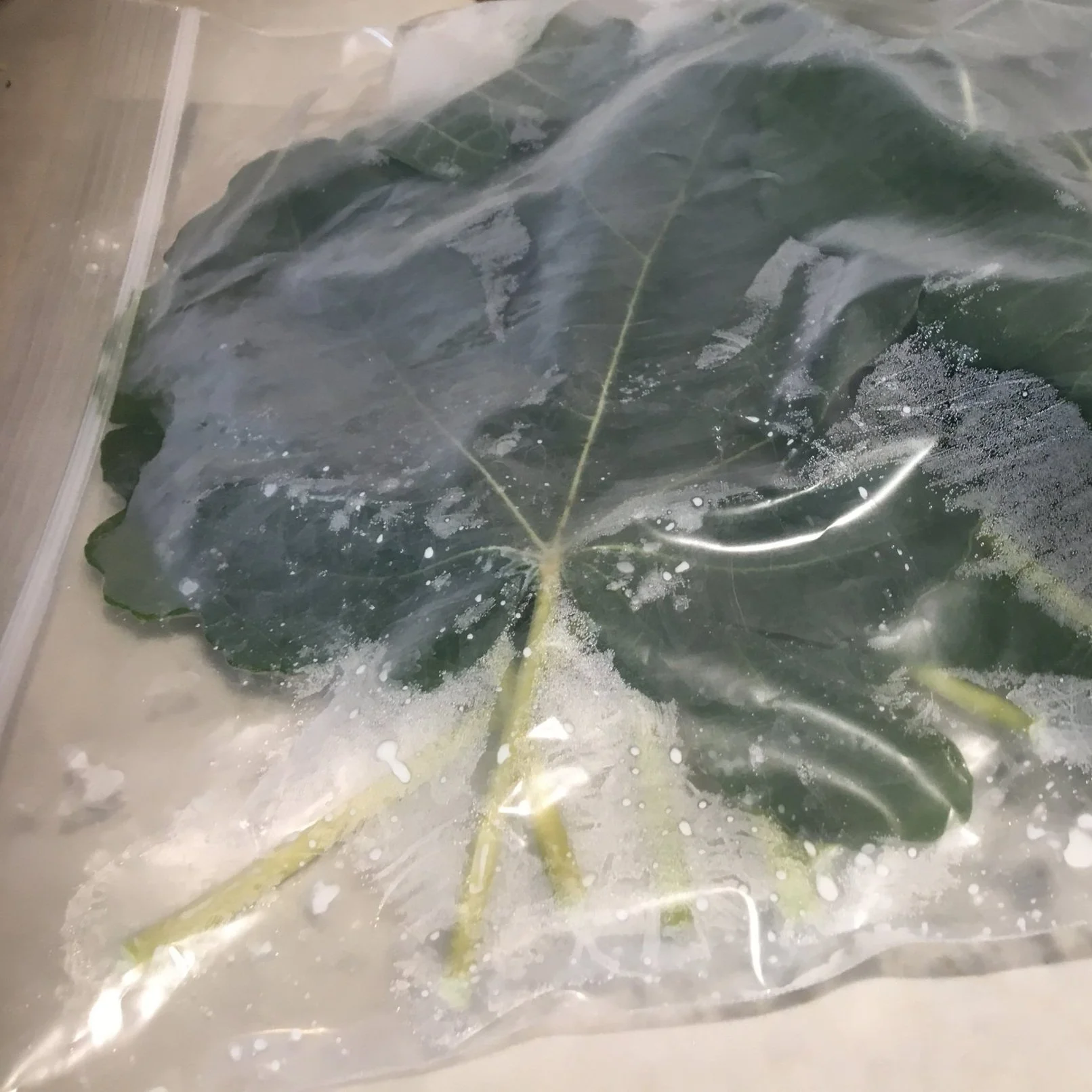

Storing Edible Flowers

Store wrapped in damp paper towel, in a sealed plastic bag in the fridge. The damp paper towel keeps the humidity high, without the flowers actually sitting in water.

Cleaning Edible Flowers

When flowers have an open structure, you can quickly spot any uninvited guests.

But if a flower has hiding spots, do give it a good rinse—or even a soak.

(I say this because once made a salad with fresh nasturtium flowers. As soon as I dressed the salad, an army of aphids marched out of those flowers. I think I ate the salad anyway…having bragged about it to my colleagues. A bit of protein...)

Tip: Edible Flowers That I Wouldn’t Eat

I don’t eat cut flowers from the store. Who knows what’s been used on them. Same with plants from the garden centre. Come to think of it, flowers from the roadside too.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More on Growing Food

Food Gardening Articles and Interviews

For more posts about how to grow your own food, head over to the library of posts.

Food Gardening Courses

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

Vegetables to Grow: 12 Tips to Choose What’s Best for Your Vegetable Garden

Choose the best vegetables to grow in your garden with these 12 crop-choosing tips.

by Steven Biggs

Choose Which Veggies to Grow in a Garden

12 tips to help you choose vegetables to grow.

“Grow radishes!”

It’s a recommendation I often hear given to new gardeners. That’s because radishes are easy to grow. And they grow quickly.

True.

But in my house, it’s the radishes that are still on the veggie platter when everything else has been devoured.

So while the easy-to-grow crops are part of a good vegetable garden plan, there are other things to think about too.

Keep reading to find out how to pick vegetable crops and varieties for your needs and situation. Instead of being prescriptive and telling you what you should grow, this post gives you 12 tips to help you choose which vegetables to grow.

1. Grow What You Love

So back to the radishes, there’s no point growing what you won’t eat—even if it’s easy to grow

Even if it’s nutritious.

Grow things you’ll enjoy eating.

2. Grow for How You Cook

I love big slabs of eggplant that I can marinate and grill, so I grow large-fruited eggplant varieties

As you choose crops and varieties, think about how you’ll use your harvest.

Here’s an example:

I love big slabs of eggplant that I can marinate and grill—or use to make eggplant parmesan. So I always go for large-fruited eggplant varieties

For tomatoes, I like to make sauce all winter, so I grow good sauce-making varieties

3. Rule Out Some Crops

There might be crops that aren’t a fit for your garden. I’m talking about space hogs—and crops that will probably be a frustration.

Space Hogs

Some crops use up a lot of space—more than makes sense in a small garden.

For example:

I love Brussels sprouts. But they’re big plants that tie up the same patch of garden for an entire season. So I leave them to the market gardeners.

I love edamame too. But for the amount I get considering the amount of space they take in the garden, they’re not my top choice.

Unnecessary Frustrations

Depending on what your situation, there might be crops that disappoint—or frustrate—you.

Here’s are examples:

Corn. I love corn. So do all the raccoons around here. So I don’t grow it. I don’t need the chest pains!

Tomatoes. Some people prefer cherry tomatoes to big beefsteak tomatoes because that way there’s lots more tomatoes to harvest. That way, the gardener gets lots even if wildlife steals some.

4. Try Something New

Have you added something new to your garden? I like to grow something new every year.

Recently it was celtuce, a.k.a. stem lettuce. It’s easy to grow and fun to cook with. Not a new crop at all…just new to me.

20 years ago I grew cucamelons for the first time and have grown them ever since.

20 years ago I tried cucamelons and have loved them and grown them every year since.

Look for neat varieties (e.g. a pepper variety I love is the corkscrew-shaped ‘Corbacci’

Or branch out into a crop from a cuisine you’re not familiar with (okra was new to me…but after I learnt a Cajun fiddle tune I wanted to learn how to make Cajun-style gumbo soup…and now I aways grow okra for making gumbo soup!)

5. Consider Diseases

Variety choice sometimes helps with disease problems. For example:

Downy mildew ravaged my basil for a couple of years. So now when I’m getting basil seeds, I look for mildew-resistant basil varieties

There’s no totally blight-proof tomatoes, but there are blight-resistant varieties, worth adding to the mix in a garden so that in years when blight decimates the tomato patch, there are still a few plants producing late in the season

6. Pick Crops for Small Spaces

If space is a challenge, crop choice can often help you harvest much, much more.

Crops for Vertical Gardening

If you’re gardening in a small space, choose vegetable crops that you can grow upwards on trellises, tee-pees, or fences.

If you’re gardening in a small space, choose veg that you can grow vertically. When you grow upwards, that frees up space on the ground—so you can fit more into a small space.

Here are a couple of my favourites:

Runner beans. I love runner runner beans! The flowers are edible, great for bouquets, attract hummingbirds. Oh, did I mention there’s beans too! (If you’re in a maritime climate, you might find runner beans produce more than pole beans.)

Zucchini: Many zucchini varieties have a bush-like growth habit, and the plant can take up a fair bit of space. But if you grow a climbing zucchini variety, it won’t take up as much space…so there’s room to plant more in your garden.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Plants with Multiple Edible Parts

You might also think about plants with more than one edible part, so in a limited space you’re getting multiple harvests from one crop

Radishes have edible seed pods.

Snap peas (you can eat the peas and the pod…and don’t forget young tendrils)

Squash (eat the flowers, the squash…and shoot tips!)

Beets (both leaves and roots are edible)

Radish (along with the roots, the seed pods are edible)

Find out more crops with more than one edible part.

Hear a chef talk about using squash shoot tips and other uncommon ingredients.

7. Choose for an Early Harvest

Look for crops and varieties that can move up your first harvest.

For example:

I like broad beans, which can be planted far ahead of all the other types of beans

Look for fast-maturing varieties (I grow fast-maturing arugula and spinach varieties in my cold frames in late winter because I want that first harvest as soon as possible)

Do the same with your beets, carrots, tomatoes and other crops

To choose faster-maturing varieties, compare the days-to-maturity information with other varieties (often called “DTM”)

8. Remember Fall Harvesting

Parsley holds up well when fall frosts arrive.

Remember to add in cool-season crops that keep producing as fall frosts arrive.

Cabbage family

Kale

Celery

Parsley

9. Choose for a Short Growing Season

If you’re dealing with a short growing season, there might be some crops you don’t want to bother with. I have friends who won’t grow eggplant and pepper.

More ideas:

Bush beans give a quicker, more concentrated harvest than pole and runner beans

Look for varieties that mature more quickly (e.g. we love Cream of Saskatchewan watermelon, which ripens melons much more quickly than watermelon varieties grown in warmer zones.)

10. Grow for Year-Round Enjoyment

Many gardeners like to enjoy the harvest year-round. If that’s you, here are some ideas:

Grow dry beans that you can easily store for later use

Look for root crops that store well (these tend to be varieties that grow larger roots)

Thought of kohlrabi…there’s a storage variety too

You can harvest leeks right through the winter when there’s a thaw

Get more crop ideas for year-round enjoyment.

11. Plan an Edible Landscape

Looking for attractive veg to add an ornamental touch to a landscape?

Here are ideas:

Asparagus looks great at the back of a perennial border, with its tall, ferny foliage

Runner beans have beautiful flowers

Lovage is a perennial with a celery-like taste, great for the perennial border

Eggplant has beautiful flowers

Kale is a great way to add colour and texture into a garden

Here are more perennial edibles.

Sometimes shade is a challenge in an edible landscape. Here are fruits and vegetables that you can grow in the shade.

If you’re serious about edible landscaping and want to create an awesome out-of-the box edible landscape, check out this course.

12. Crop Substitution for Less Work

Pin this post!

Keep your workload to a minimum through crop choice!

Here are examples of the type of thinking you can use to make less work for yourself.

Leaf celery instead of stalk celery. Stalk celery takes lots of water and feeding to get tender, crispy stalks. Leaf celery doesn’t make big stalks—you just get lots of leaves on short stems, and it’s far less bother if you don’t mind consuming celery this way. (I chop it into soups, stews, and salads for that same celery taste.)

Ground cherry instead of cape gooseberry. I actually prefer the taste of cape gooseberries…but they need a longer growing season, meaning I have to start the seeds earlier, and then give them prime, hot, garden real estate to get a decent harvest. Ground cherries are far easier to grow. (Find out more about these two different husk cherries.)

Broccoli instead of cauliflower. Not only is cauliflower more finicky, to get snow-white heads it must be blanched, which is often done by tying leaves over the head with an elastic. It’s a lot of bother compared to broccoli, which requires no blanching.

Squash instead of potato and sweet potato. Squash is far less work. Instead of transplanting sweet potato plants, you just poke squash seeds into the soil. And instead of digging out sweet potato roots, you just snip squash from the vine. You still get the sweet, orange ingredient for baking.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More on Vegetable Garden Planning

More on Growing Vegetables

Vegetable Gardening Articles and Interviews

For more posts about how to grow vegetables and kitchen garden design, head over to the vegetable gardening home page.

Vegetable Gardening Courses

Wood Ash for the Garden: What You Need to Know

Find out whether wood ash is good for your garden. It can be used as a fertilizer and to make the soil less acidic.

By Steven Biggs

Fireplace Ashes for the Garden?

I have happy memories of cooking holiday roasts over charcoal with my dad. He taught me how to cook over charcoal—and he drilled in the importance of NEVER leaving a barbecue full of ash out in the rain.

Wet ash in a barbecue is like road salt on a car…corrosion just waiting to happen.

Yet many people spread wood ash on the garden.

Actually, sprinkling ash around the yard isn’t anything new. And in an era when people pay attention to how much waste they generate, it seems to make sense not to send wood ash to landfill.

My neighbour Al always sprinkled wood ash around his garden. I’d see the ash as the wind blew it over the fresh snow, and ash specks peppered the sidewalk.

Whether wood ash is good for your vegetable garden depends on your soil and how you’re using the ash.

Thinking further back, I remember as a child, playing on my grandmother’s gravel driveway and eagerly collecting the nuggets of coal clinker from decades before, when ash from the coal furnace was sprinkled around the yard.

But is ash good for the garden? The answer depends on what type of ash it is, how you’re using it, and your soil.

If you’re wondering about using ash in your yard, this post tells you more about wood ash, ways to use it—or when not to use it.

What’s in Wood Ash

Wood ash contains a lot of plant nutrients, including potassium, phosphorus, calcium and magnesium. There are other minor nutrients too.

The amount of the various nutrients in your wood ash depend on the type of wood you’re burning.

The other thing to know is that wood ash is alkaline. So in the same way that lime is used to make soil less acidic, so can wood ash. (More wood ash is needed than lime, though wood ash is faster acting.)

Using Wood Ash in the Garden

Ash has two uses in the garden:

Fertilizing