Eat Your Own Fresh Tomatoes in March! Grow Storage Tomatoes

By Steven Biggs

Long Keeper Tomatoes Last all Winter

With the right tomato variety, you’ll still be eating your own fresh tomatoes in early spring. It’s often March by the time I use up my fresh tomatoes.

That’s right. March.

Yet I picked the tomatoes the previous October, just before the first fall frost.

Tomatoes that store well are called long-keeper tomatoes, keeper tomatoes, storage tomatoes, or winter tomatoes.

These storage tomatoes are a simple way to add fresh, homegrown veg to the winter menu. Perfect for home gardeners.

If you’re interested in growing long keeper tomatoes, keep reading to find out how you can enjoy your own homegrown tomatoes over the winter.

What’s a Long Keeper Tomato?

Let’s be clear: Long keeper tomatoes are NOT like a thin-skinned, juicy tomato.

They’re thick-skinned. It’s because of that thick skin that they last a long time without spoiling.

Storage Tomato…Not a Thin-Skinned Slicer

I once gave long keeper tomato plants to my neighbours Joe and Gina. They were avid veg gardeners. Loved tomatoes. I thought they’d love the idea of having their own storage tomatoes all winter long.

But they hated my keeper tomatoes…

That’s because they loved juicy tomatoes for sandwiches and meaty tomatoes for sauces. Keeper tomatoes are for storage—they’re not summer sandwich material.

Expecting a keeper tomato to be like a beefsteak tomato is like expecting a pickup truck to drive like sports car. Ain’t going to happen. The purpose of each is quite different.

When to Sow Long Keeper Tomato Seeds

Because I harvest my keeper tomatoes at the very end of the season, there is no point to starting them too early. (My first fall frost is usually late October—so that means I’m only harvesting the keeper tomatoes in October.)

I start my summer-eating tomato varieties 6-10 weeks before the average last frost date, so that I can enjoy fresh tomatoes as soon as possible.

But I only start the keeper tomato varieties a couple of weeks before the last spring frost. Then I transplant them into the garden when the plants are big enough.

Want to grow your own storage tomatoes from seed? Get tips to grow great tomato seedlings at home.

How to Grow Storage Tomatoes

In the garden, grow storage tomatoes as you would other tomato varieties. The main difference is that there’s less of a rush to get them going early.

Here’s a guide to staking tomato plants.

How to Store Long Keeper Tomatoes

If you have only a few storage tomatoes, put them in a bowl on the counter; they last well and look nice. But for longer-term storage, a slightly cooler temperature is better. That way, they’ll last longer. I store long keeper tomatoes in a cool basement room, spread out on a tray.

Hurray! No processing, no freezing.

Here’s another way to store keeper tomatoes: Leave the tomatoes on the plant, and then harvest the whole plant. Then, hang the plant upside down, somewhere cool. The tomatoes continue to ripen on the plant.

Wondering about how to ripen all the other green tomatoes left in your garden in the fall? Here’s an article that tells you how.

How to Use Keeper Tomatoes

Keeper, or “winter,” tomatoes are perfect for chopping up to use in salads and in cooking.

My favourite way to use them is in bruschetta.

Tomatoes in March. Grow a “keeper” or “winter” tomato.

Long Keeper Tomato Varieties

My first long keeper tomato variety came from my Dad’s friend Dino. Dino simply called it a “winter tomato.” So I just call it Dino’s Winter Tomato.

When it’s ripe, the skin has an orange colour; and when you cut into it, the flesh has a light red colour.

There are many keeper varieties around. Here are some to try:

‘Long Keeper’ is an old variety that’s widely available.

Prairie Garden Seeds sells a keeper tomato called ‘Clare’s Tomato’.

‘Green Bee’ is a firm-when-ripe tomato that grills well—and it’s also an excellent storage tomato.

Looking for a beautiful keeper tomato? Then try ‘Evil Olive’. It’s a great storage tomato. (Don’t be put off by the name, it’s lovely!)

‘Fakel’ is an old processing variety with a thick skin. It’s a medium-sized red tomato that’s good for fresh eating and storage. So if you want something that’s good sliced but also stores well, a good option. (Determinate plant, so good if you’re doing container gardening.)

‘Piennolo del Vesuvio’ is an Italian heirloom from the area around Mount Vesuvius. It forms clusters with cherry-tomato-sized fruit having a pointy tip. The clusters are traditionally picked and hung indoors to slowly ripen through the winter.

More on Tomatoes

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

Course: Tomato Overload Masterclass

Want to up your game growing tomatoes?

This self-paced course helps you choose great varieties, grow great seedlings, give plants the care they need, and enjoy an abundant harvest.

Guide to Direct Sowing Seeds (Why and When to Skip the Transplants!)

Find out how and what to direct seed in your vegetable garden.

by Steven Biggs

Why Direct Sow Seeds?

Ever had transplants that put on the brakes after you move them to the garden?

It’s disappointing.

But a big transplant isn’t always better than a wee seed.

Sometimes, it’s better to plant seeds straight into the garden.

This is called direct sowing, also called direct seeding or direct planting.

This post tells you how to direct sow, best crops for direct sowing—and simple ways to sow seeds in a home garden.

What is Does Direct Sow Mean?

Direct sowing is when we sow seeds—plant seeds—directly in the garden.

This is instead of starting seeds indoors and then move them to the garden later—known as growing “transplants.”

Why Direct Sow Vegetable Seeds?

There are many reasons to direct-sow vegetables.

Here are a few reasons:

Pin this post!

Easier (there's no need to care for seedlings indoors)

Less expensive (no need for potting soil or containers)

Less environmental footprint (yeah, your coir-based and peat-based potting soils have an environmental footprint)

Saves indoor seed-starting space for crops that really need to be started indoors

No need to “harden off” young seedlings before planting them in the garden

Some crops don’t transplant well…and don’t bounce back well from transplanting

When to Direct Sow Seeds

It’s tempting to start direct sowing as soon as the soil thaws in the spring. But it’s often best to wait a bit. Moisture and temperature are two things to consider as you decide when to direct sow your seeds.

Moisture

If the soil is really wet, it can be difficult to get it ready for direct seeding.

The soil might stick to your tools, or might be clumpy and hard to spread around.

Another reason not to work in your garden when the soil is still very wet is that it’s easy to compact the soil—which messes up drainage and makes conditions less suited to your crops.

Temperature

The ideal temperature varies by crop. But in general, when things are still really cold and wet, there’s more chance your seeds will rot before they start to grow. Soil in raised beds warms up more quickly.

In this guide to when to start seeds indoors I also give talk about when to direct seed some crops.

Direct Sowing isn’t Always the Best Choice

Direct seeding isn’t the best choice for all crops, or in all situations. Here are a few things to consider:

In areas with a short growing season, crops that take a long time to mature are usually grown from transplants.

Slugs and other bugs can devastate small, direct-sown seedlings as they emerge…whereas a larger transplant might get through some insect damage.

During hot summer weather, seed germination can be spotty (see below for a summer seed-sowing hack). So crops that we direct sow in the spring are sometimes started indoors and then transplanted during hot summer weather.

In low-lying area, the garden soil might be too wet to direct sow seeds in the spring.

Here’s one more: You’re new to gardening and won’t know the difference between emerging direct-seeded crops and the weed seedlings!

How to Direct Sow Seeds

Before sowing seeds, prepare the soil.

Start by preparing the soil ahead of time. When sowing seeds, we want to break up any crust on top of the soil surface, and break up bigger chunks of soil. That way, germinating seeds don’t hit roadblocks.

(Yes, there’s a whole body of work out there on no-dig techniques—and there is a time and place for this…but if you want the best results when direct sowing, prepare the soil.)

Planting Depth

Use the size of the seed as a guide to planting depth. Seed packets usually recommend a depth too.

Plant the seed about twice as deep as it is wide. Too shallow is better than too deep.

But don't feel as if you need to measure and be precise.

If you’re planting seeds into trenches, you can make well-spaced trenches using a garden rake that has pieces of pipe on it.

Like most things in gardening (and life), direct sowing isn't an exact science.

Trench for Sowing Seeds

If you direct-sow seeds in rows, make a trench with your trowel or the corner of a hoe.

Then, place your vegetable seeds into the trench, and cover with soil.

OR, make your trenches by fitting pieces of pipe onto a garden rake! (See the photo.)

Poke Seeds in the Soil (Planting Seeds Simplified!)

This is low-tech and might be laughable to a commercial grower—but in a home-garden setting, can be a simple approach to direct sow seeds!

I drop large seeds into place, and then just poke them into the soil. Then I scuff the soil to fill the holes.

Poking works well for larger seeds that you can easily see:

Poking large seeds into the soil is a simple way of planting seeds.

Peas

Beans

Beets

Swiss chard

Squash

Zucchini

If you’re planting a whole block with seeds, as I like to do with beets and Swiss chard, you can do what I call the “scatter-and-poke” method. Scatter seeds to approximately the spacing you want—and then poke them into the soil. Scuff soil to fill in holes.

(Gardening is a great cure for perfectionism, and the scatter-and-poke approach dispenses with all notions of perfection in a garden!)

Broadcast and Cover

You can sprinkle small seeds such as these carrot seeds by hand, and then cover with soil.

If you’re filling a block or wide row with small seeds (e.g. carrot or lettuce), sprinkle by hand, and then cover with soil.

You might wonder, “Where do I get the soil I’m covering the seed with?” Rake aside some garden soil before you sprinkle your seed in place—and replace it over top of the seed afterwards.

Broadcast and Rake!

I’m always interested in methods that make my life simpler. And raking aside soil before I broadcast seed is a bother.

So I simply broadcast the seed, and then use an up-and-down motion with a hand rake to work some of those seeds into the soil.

Note: There will be some seeds that aren’t at an ideal depth. That’s OK. I’m a home gardener—not a commercial grower. I just seed more heavily to compensate.

Direct Sowing Hacks

Using a broadfork to make straight rows.

Folded paper. Forget the seed-dispensing gizmos for small seed. Fold a sheet of paper in half. Pour seed onto the folded sheet. Now, use a pencil or a nail to dispense individual seeds off the end of this folded sheet. Low tech, yes—but works well.

Broadfork. When my daughter, Emma, wanted side-by-side trial rows of a number of crops, she used the broadfork to make a tidy set of trenches. (The broadfork is normally used to loosen soil…but this works nicely!)

Seed tape. Seeds embedded in a strip of biodegradable paper. Yeah, a bit gimmicky. I don’t use this. But if you’re gardening with kids, or you have shaky hands and can’t easily dispense seed, it can be useful.

Using boards to keep the soil moist for direct seeding in the summer.

Pelleted seed. Small seeds bulked out with a clay coating. Like seed tape, you pay more per seed. But again, could be useful if you’re direct seeding with kids, or you’re having trouble coping with smaller seeds.

Boards. Yup, low-tech boards over summer-sown small seeds can be a life saver. In summer heat, soil can quickly form a crust that seedling have difficulty breaching. But a board over the soil during the germination window keeps the soil underneath moist. No crust.

Web trays. As soon as squirrels see freshly turned soil in my garden, they’re eager to disinter seeds. It’s infuriating. Who would have thought there’s a higher purpose for those horrid plastic webbed trays that the horticulture industry so loves! Inverted web trays over top of your directly sown seeds keep digging varmints at bay.

Direct Seeding by Crop

Take that, squirrels!

Leafy Greens. I grow transplants of leafy green crops such as lettuce, spinach, and Swiss chard. I also direct-sow seeds into the garden.

Why both ways?

So I have a succession of harvests.

(It is also insurance. If weather or pests cause less successful results one way, I have a backup!)

Root Crops. I direct sow all my carrots, parsnips, and beets. These crops can all be direct-sown in the garden early. And they don’t respond well to root disturbance.

“Fruit” Veg. For those fruits that we insist on calling veg—tomatoes, peppers, and eggplant—I grow everything by transplants because I’m in a cold climate and I extend the harvest window with transplants.

Vine Crops. The vine crops in the squash and cucumber clans don’t respond well to root disturbance. So direct sowing is always a good strategy.

(But, like the leafy greens, I hedge my bets and both direct sow and start a few transplants.)

Top Direct Seeding Tip

If conditions get really dry just as your seeds are starting to grow, tender young leaves and roots can dry out quickly…and it’s game over.

Keep the soil well watered!

FAQ Direct Sowing

What vegetables can be direct sown?

Direct sow root crops such as beet, carrot, parsnip, radish, and turnip.

Direct sow leafy greens including chard, kale, lettuce, mizuna, and spinach.

Direct seed legumes such as beans and peas.

Do I need to thin direct-seeded crops?

That depends on how much seed you use. In commercial production, growers often use precision-seeding devices so that the seeds are perfectly spaced. So no need to thin. But that’s approach isn’t always practical in a home-garden setting where we’re dealing with smaller, irregularly shaped spaces.

My approach is to direct sow with lots of seed, and then thin out extra plants while the plants are still small. So, as I thin out young spinach plants, I have baby salad greens for supper!

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

Courses

Here’s a course that guides you through creating an edible garden you love. It’s my ode to edible gardening. You’ll find out how to think outside the box and create a special space. Get the information you need about a wide range of edible plants.

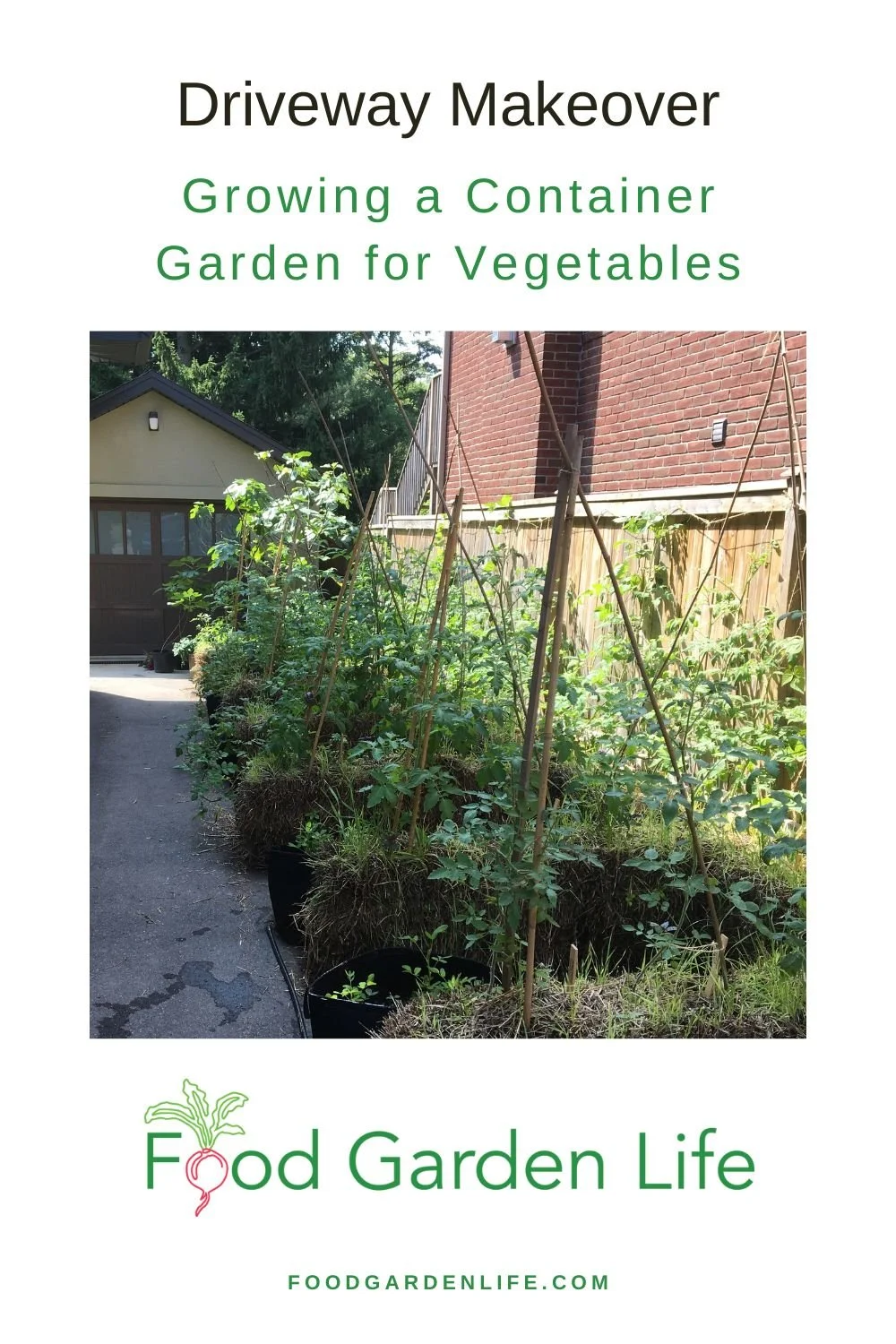

Driveway Makeover! 5 Ideas for Growing a Container Garden for Vegetables

A container vegetable garden is a good way to fit lots of vegetable crops into a small space. Find out how to get started.

by Steven Biggs

My Driveway Container Vegetable Garden

Not enough space to grow everything you want? Be creative! A container garden is a great way to fit more vegetables into your yard.

Here’s our driveway container garden. The driveway container garden is a quick, temporary space-making solution so we can grow extra tomato, pepper, potato, summer squash, and chard plants.

In this vegetable container garden, we use straw bales, fabric pots, nursery pots, bushel baskets, and vertical gardening techniques to make the most of the space.

Do you have an underused space that you can use for growing food? Many yards do. It could be a driveway, patio, or even the hard-packed space alongside a hedge. In this post, I look at how to add growing space to your yard.

Ideas for Your Vegetable Container Garden

Container gardening is part science, and part creativity. There are lots of ways to approach it. Here are five ideas we’ve used to make the most of our driveway for growing vegetables.

1. Strawbale Gardens: Grow Vegetables in Containers that are Biodegradeable

Wetting the straw bales to start the “conditioning” process.

A lot of visitors take a second look at my straw-bale garden and wonder where I put the potting soil. There is no potting soil: The straw bale is both the container and the growing medium. No potting mix required!

The decomposing straw gives plant roots needed air while retaining moisture…like a big sponge.

By the end of the season, when we pull apart a bale, the inside is dark and crumbly. It’s already partially composted and perfect to use as mulch on our gardens. Then, we start again with new bales the following year.

We plant the top of each straw bale with tomato plants and leafy greens. Then we put bush beans on the sides of the bales. (Just poke the bean seeds into the bale!)

Important: If you’re starting with new, fresh, dry bales, the first step is to get microbial activity underway by watering them and feeding them. This step is called “conditioning.”

I’m a big fan of straw-bale gardening. If you plant to do it for the first time, make sure to condition the bales properly. Find out more about straw-bale gardening and how to condition the bales.

2. Bushel Baskets: Growing Vegetables in Repurposed Containers

Container vegetable gardening with repurposed stuff! Potatoes growing in lined bushel baskets.

We often have extra bushel baskets from our fall cider-making. So we use them for growing potatoes. (We can’t grow potatoes in our back yard because our neighbour’s black walnut tree gives off a compound that kills them. Here’s more on black-walnut toxicity.)

We line the bushel baskets with plastic bags so that the potting soil stays moist longer and so the bushel baskets won’t decompose as quickly. (Important note: We poke drainage holes in the bottom of the bags!)

There are lots of repurposed items that work well as containers. Here are a few ideas:

Milk crates. I’ve used these in previous gardens. Just cover the openings on the side and bottom with newspaper or cardboard, so the soil doesn’t escape.

Old wheelbarrow. A friend uses an old wheelbarrow as a driveway planter.

Wash basins. I have neighbours who use metal wash basins as vegetable garden planters. (Make sure to drill drainage holes in the bottom.)

3. Fabric Pots: Garden in Pots that are Moveable

Fabric pots are moveable, and a great way to start container gardening.

These pots are widely available. What we like about them is that they have handles so we can move them aside if we need to move anything large along the driveway.

I’ve seen impressive rooftop container gardens created with fabric pots. While some gardeners use drip irrigation to keep the soil consistently moist, a more simple approach is to put a saucer underneath; as the potting mix begins to dry, water in the saucer wicks upwards.

4. Fence: Grow Vegetable Plants on Surrounding Features

We train tomato plants up the twine that is dangling from the top of the fence.

Sometimes it’s possible to squeeze more crops into a space by growing some of them upwards—a concept that’s often referred to as “vertical gardening.” In the case of our driveway, there’s a wonky board fence that I like to hide with a wall of tomato and squash!

We plant tomatoes next to the fence, and then train them up twine suspended along the fence. We also grow squash vines along the fence—well past where the garden is.

Idea: I’ve also grown squash along hedges and up trees. Because the vines roam around, there are lots of vertical-gardening possibilities.

Here’s more about vertical gardening.

5. Nursery Pots: Figs Growing in Containers

Next to my garage is my potted fig “orchard.” It’s a collection of potted fig plants growing in nursery pots. These fig trees spend the winter in my garage.

Nursery pots are an inexpensive way to start container gardening. Talk with garden centres and arborists—you can often get them for free or very inexpensively.

If you’re interested in growing figs in a cold climate, here’s more about how to do it.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Plan Your Container Vegetable Garden

Choose the Location

If you’re thinking about a container vegetable garden but don’t know where to start, choose your location first.

Then, once you’ve decided on a location, you’ll know how much sunlight you’re dealing with. Remember that full-sun crops such as tomatoes can do respectably well in partial sun. (This is not something a commercial market gardener would do…but if you’re a home gardener, conditions often aren’t perfect.)

Something else to think about is access to water. Is there a tap or hose nearby?

Choosing Container Plants

When it comes to choosing container gardening crops, a good starting point is things you like to eat.

Then, think about crops that do well in containers. Most vegetables grow well if a container is big enough, but some crops are more practical than others.

For example:

Pole beans are great if they're next to something they can grow on, but, otherwise, bush beans are more practical because you don't need to make a trellis.

Parsnips and Brussels sprouts take the whole summer and fall to mature. Instead, look for crops that mature more quickly, like carrots and carrots.

Here’s a list of best vegetables to grow in pots.

If the location is shady, here’s a list of crops that grow in shade.

Need Inspiration?

Here’s our chat with a gardener who grows a whole garden full of hot peppers in containers.

Consider Containers with Reservoirs

A key to success—and common reason for failure—with container vegetable gardening is watering. When the soil in containers regularly dries out, your vegetable plants put on the brakes. Growth stalls. Or, even worse, your plants skip straight to flowering before they're big enough.

Pin this post!

(When you’re looking for bargain plants at a big-box store and see what looks like a bonsai cauliflower plant that’s only six inches tall, chances are that the plant got parched too often…and that stress made it flower before its time.)

If the potting soil is consistently moist, your crop will be miles ahead. It makes a big difference.

You can keep the potting mix consistently moist with what’s called “sub-irrigated” pots. This is just a fancy way of saying a container with a reservoir. As the potting mix begins to dry, water from the reservoir wicks upwards, keeping the soil continuously moist.

This sort of container is widely available—but you can easily make your own.

Find out more about sub-irrigated (a.k.a. self-watering) pots.

More Container Ideas

If space is tight, small containers might be your only option. I've made herb container gardens by dotting potted plants on a staircase.

Don't forget window boxes. Although they're shallow, they work well for shallow-rooted crops such as leafy greens.

Hanging baskets are a great way to fit more vegetable plants into your container garden.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

Best Juglone-Tolerant Plants for Food Gardens Near Black Walnut Trees

By Steven Biggs

Growing Food Crops Near Black Walnut Trees

I bought my current home in the late winter when there were no leaves on the trees. So I didn't notice that the massive black walnut tree next door. Yikes! It's created a lot of gardening hurdles.

Black walnuts are known for their beautiful wood. Prized in fine woodworking. But there's a sinister side too...they have the odious reputation as trees that poison nearby plants.

A commercial grower or a gardener in a rural area might react with a chainsaw. Not an option for most home gardeners. Especially in the city where trees have the same rights as taxpayers.

But I've figured out how to grow a thriving vegetable garden, edible landscape, and fruit crops all around that black walnut tree. If you want to grow food crops alongside these beautiful but challenging trees, keep reading: This post tells you what you need to know to successfully grow food plants—even if your yard is overshadowed by a black walnut tree.

Primer: Black Waltnut Toxicity

Black walnut (Juglans nigra) trees give off something called juglone, which can affect the growth of nearby plants. Not a bad thing from the walnut's perspective...because there's less competition.

Juglone is in all parts of the black walnut tree, including the roots, leaves, and the nuts.

Not all plants are affected by juglone.

As juglone builds up in the soil under and around the tree, it affects nearby susceptible plants.

If you like the technical lingo: When a plant makes something that inhibits the growth of other plants, it's called "allelopathy."

Tips for Gardening Near Black Walnut Trees

Sources of Black Walnut Toxicity

Let's take a look at how juglone gets from the tree into your soil. If there's a walnut tree, you'll have more juglone than you want. But you can do some things to reduce black walnut toxicity in your garden.

Black walnut hulls also contain juglone.

Roots. Walnut tree roots release juglone into the soil. Remember the black walnut roots if you're thinking of raised-bed gardening, because tree roots can (and do!) grow up into raised beds. You need a raised bed that the roots can't get into. (See below, Raised Beds.)

Leaves. I don't bother removing walnut leaves from my vegetable garden beds near the black walnut tree. Those beds are already loaded with juglone. But I do remove fallen walnut leaves from my raised beds, where the soil is not contaminated with juglone. I don't compost black walnut leaves with leaves from other parts of my yard. No point making killer compost. (Composting breaks down juglone, but in a home garden we don't have perfect composting conditions, so you won't know how long until your compost is juglone-free.)

Nuts. Black walnut hulls also contain juglone. Again, I removed them from the raised beds where the soil isn't full of juglone. If I'm not fast, the squirrels help with cleanup! Bothered by squirrels? Here are 50 ways to foil squirrels in your food garden.

Wood. If you're getting a load of wood chips from an arborist, make sure there isn't chipped black walnut in there!

Other trees in the same family as black walnut (the Juglandaceae family) give off juglone too. These include butternut, pecan, English walnut, heartnut, and hickory. But black walnut gives off the most, hence its reputation and the term "black walnut toxicity."

How Big is the Walnut "Kill Zone"

The bigger the tree, the bigger the zone where you’ll get black walnut toxicity. My neighbour’s tree is big…and so is the kill zone.

I remember hiking in a nearby ravine with a semi-wooded, scrubby area. The scrub was dotted with young black walnut trees. And underneath these young trees there was mostly grass. Like a doughnut under each tree. Far less competition. I call that the "kill zone."

The size of this kill zone in your yard depends on how big the tree is and how well drained the soil is. Soil drainage, soil type, and microbes are involved in breaking down juglone. That just means that determining the size of the kill zone is not an exact science.

When I first started gardening near my neighbour's big black walnut tree, I figured that if I planted beyond the "drip line" (which is what's under the tree canopy) it might be OK.

It wasn't.

The young espaliered apple trees I'd worked hard to shape? Toast. Even though they were 15 metres away. The effects of juglone can extend well beyond the drip line of big trees. For a big tree, I'd use 15 metres as a starting point. The farther the better.

Symptoms of Juglone Toxicity

Juglone can cause yellowing leaves, partial or total wilting, stunted growth, and, possibly, death of susceptible plants.

The symptoms might look like drought stress at first. That's what I saw the first time it affected our tomato crop: Wilting even when there was ample soil moisture. But by then, it's too late. Game over. No matter how much you water.

Walnut-Wise Food Gardening

3 Steps to Create a Thriving Vegetable Garden or Edible Landscape Near a Black Walnut Tree

Consider the kill zone. Once you've mapped out the likely kill zone, you can start planning where to put your juglone-sensitive plants, and where to put your juglone-tolerant plant species. Play it safe, and assume the kill zone is bigger rather than smaller.

Choose wisely. There are oodles of plants that are tolerant to juglone. Use the lists below to help you choose what to grow—and what not to grow.

Keep crops out of affected soil. Use containers and raised bed to grow juglone-sensitive plants close to a black walnut tree. But you have to do it right. (But see Raised Beds, below, so that you do it right.)

Underneath my neighbour's black walnut tree I have a small pawpaw patch (these are shade-tolerant native plants with a really tasty fruit, worthwhile working into your walnut-wise garden.) There's also small fruit such as bush cherries, chokeberry, and autumn olive closer to the edge of the dripline, where there's more sunlight. Then, further out, where there's a bit more sun, I have raised beds for juglone-sensitive plants. And finally, still within the kill zone, I have a really big veg patch, filled with crops that aren't affected by juglone.

Container Veg Gardening Course

As well as helping with your walnut problem, a container garden is a great way to harvest more from a small space. If you want to take container gardening to the next level, check out the course below on vegetable container gardening.

Raised Beds and Containers to Solve Black Walnut Toxicity

A raised bed allows you to grow juglone-sensitive crops in the kill zone. But you have to set it up properly...or it won't help for long. Tree roots grow up into raised beds.

This is a wicking bed, very close to a black walnut tree (see the tree trunk in the back corner of the photo.) A wicking bed is one way to grow juglone-sensitive plants near a black walnut tree.

Failure 1. My first attempt at growing tomatoes in the ground near the tree failed. To be expected. So I reasoned that if I made a simple wooden raised bed, lined the bottom with landscape fabric, and added uncontaminated soil, it would solve the problem. At first, it seemed to work. But by mid summer, the tomatoes wilted badly. The reason? The roll of fabric wasn't as wide as the bed. And even though I overlapped the fabric so that the "new" soil above was separated from the contaminated soil below, tomato roots could find their way into the soil below...and walnut roots could grow up into the raised bed.

Failure 2. Another year I tried strawbale gardening. I reasoned that I could grow tomato plants in bales, near the walnut tree, if I put down a layer of plastic mulch under that bale to keep the tomato roots out of the soil below. This might have worked...except I used a biodegradeable plastic mulch, and part way through the season those tomato roots made the journey to juglone hell. Game over. (But strawbale gardening is an excellent technique. Find out how to use strawbales to create awesome food gardens.)

Success! I realized that tree roots quickly grow where they're not wanted...and the same goes for tomato roots. So I needed a bed that isolated the tomato roots. The answer was something called a "wicking bed." In short, it's a bed that has a thick liner at the bottom, creating a reservoir. They're usually used in dry areas, as a way to conserve water...but they fit the bill perfectly. Here's more information about using wicking beds.

On a smaller scale than a raised bed such as a wicking bed, container gardening is another way to grow sensitive plants near a black walnut tree. I'm a big fan of sub-irrigated planters (a.k.a. SIPS), which, like wicking beds, cut back on how often you need to water. Here's more about SIPS.

Plant Lists for Walnut-Wise Food Gardens

Here are edible plant lists you can use to plan your walnut-wise garden. These are from my experience and from published sources such as extension agencies and universities. Sometimes recommendations by published sources differ, so consider this a guide—not cast in stone.

Juglone-Sensitive Plants

Sensitive Plants - Fruit Trees and Shrubs

Apple

Crabapple

Blackberry

Blueberry

Sensitive Plants - Vegetables

Peppers and other plants in the nightshade family are sensitive to juglone.

Wondering what vegetables are sensitive to juglone? Plants in the nightshade family (Solanaceae) practically wilt at the mention of juglone. This family includes lots of the must-grow veg crops such as tomatoes, peppers, potatoes—but also some less common ones such as cape gooseberry and ground cherry.

Asparagus

Cabbage and family

Eggplant

Pepper

Potato

Rhubarb

Tomato

Plants Tolerant to Juglone

Wondering what grows well near a black walnut tree? Many plants grow just fine under or near a walnut tree. So if you're wondering how far should a garden be from a black walnut tree, you can garden quite close to the tree if you choose juglone-tolerant plants and take into account the shade. Here are key edible plants to get you started.

Juglone-Tolerant Plants - Fruit Trees and Shrubs

Saskatoon is an example of a fruit bush that is not juglone-sensitive.

Wondering what fruit trees are juglone tolerant? You have a lot of choice!

Autumn Olive (loved by foragers, though disliked by some because it can be an invasive here in Southern Ontario)

Cherry, Peach, Plum, Nectarine (fruit trees and bushes in the Prunus clan, what people often call stone fruit)

Chokeberry

Elderberry

Figs

Grape

Hazelnut

Pawpaw

Black raspberry

Serviceberry (including saskatoon, a.k.a. juneberry)

Here are 5 types of bush cherries you can grow.

Find out how to grow saskatoons.

Juglone-Tolerant Vegetable Crops and Herb Crops

Wondering what vegetables and herbs will tolerate juglone? There are many vegetables that tolerate juglone, so you have quite a few options.

Here’s a corner of the veg patch I have near the black walnut tree, where I grow carrots, beets, parsley, basil, squash, and corn very close to a large black walnut tree.

Basil

Bean

Beet

Carrot

Chive

Corn

Cucumber

Dill

Edamame (which is soybeans while they're still green)

Garlic

Leek

Melon

Onion

Parsley

Parsnip

Pea

Squash

Swiss chard

Other Walnut-Tolerant Edible Plants

Bee Balm (edible petals)

Dandelion (sure some people think of this as a weed, but great for early greens in the spring!)

Daylily (edible flower buds, here's more on edible flowers)

Grains such as wheat, millet, and sorgum

Hawthorn

Hosta (edible leaf spears in the spring!)

Jerusalem artichoke

Mint

Nasturtium

Pin cherry and choke cherry

Redbud tree (edible flower buds)

Rose (edible petals, rosehips)

Staghorn sumac

Looking for edible flower ideas? Check out this list of edible flowers for home gardens.

Landscape with Fruit Course

It the above list of juglone-tolerant fruit has you thinking of planting fruit near your black walnut tree, here’s a course all about how to grow fruit in home gardens.

How to Use Black Walnuts - Yes, You Can Eat Them!

Black walnuts with husks removed.

While you're not likely to find black walnuts for sale, they are quite edible. Like other nuts, remove the hull and then air dry the nuts.

Note: The husk stain. I learned the hard way one year when my hands were a few shades darker for a week after hulling black walnuts. Someone later told me that a good way to get off the hulls is to pile the nuts until the hulls soften, and then send in kids dressed in old clothes and rubber boots to jump on the pile. I haven't tried it myself, but sounds as if it would work!

The challenge with black walnuts is cracking the shell. They're much more difficult to open than an English walnut. There is a vice-like device for cracking them open. I use a hammer. Or, I've heard of people driving over the nuts!

Key Takeaways

Pin this post!

Black walnut trees give off a chemical called juglone, which affects some plants. This is sometimes called black walnut toxicity.

This doesn't mean that you can't garden hear a black walnut tree—but that you need to choose tolerant plants and use raised beds or containers.

The size of the affected area around a tree depends on its age, the soil type, and soil moisture.

FAQ

Can I just cut down my black walnut tree to solve the problem?

Sorry...that would still leave lots of roots all through the soil, and, therefore, lots of juglone. Because it can take a few years for all the roots to decay, it's not a quick fix. In short, juglone can persist for a few years after a black walnut tree is removed.

How far should a garden be from a black walnut tree?

For a mature tree, the kill zone extends beyond the tree canopy and can be more than 15 metres from the trunk.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

Food Gardening Articles

Food Gardening Courses

Find out how to grow more great food at home with our online courses. We have both live and self-paced courses.

How to Grow Tomato Seeds Indoors

A complete guide to growing tomato seeds indoors. Tips, supplies—and what to avoid.

By Steven Biggs

Learning How to Plant Tomato Seeds

How to grow tomato plants from seed.

When I was 10 years old my grandfather helped me sow tomato seeds. My first yellow-fruited tomatoes.

I had the perfect teacher. Dido was a life-long gardener and retired market gardener.

He was visiting us from Calgary that spring. We didn’t have much in the way of seed-starting supplies at our place. So he just grabbed an unused wash basin. We put a couple of inches of potting soil in it, sprinkled seeds on top. And then a thin layer of soil.

I gave lots of yellow tomatoes to the neighbours that summer!

His no-fuss approach to gardening coloured mine. There are lots of great supplies, gadget, and tricks…if you want. But you can also make gardening—and growing tomato seeds—really simple. And in a home-garden setting, I think simple is good.

In this article I share ideas about how to grow tomato seeds in a way that suits your situation.

Choose a Tomato Variety

Find out how to grow tomato plants in a way that suits your situation.

Before planting, select a variety that gives you what you want.

Here are things I think about as I choose varieties:

Colour

Size

Taste

How long it takes to mature

Plant stature (determinate tomatoes, indeterminate tomatoes, dwarf tomatoes…there are even micro-dwarf tomatoes)

Disease Resistance

How I use the tomatoes (sauce, sandwiches, packed lunches)

Storage properties (there are storage—a.k.a. “keeper” tomatoes!)

Find out about “keeper” tomatoes.

Get tomato-choosing tips in this article by my tomato-crazy daughter, Emma.

Got problems with squirrels? Cherry tomatoes might be better than big beefsteak tomatoes because there are more tomatoes to go around. Here’s a guide with 50 ways to foil squirrels.

When to Start Tomato Seeds Indoors

Start tomato plants indoors to get a head start on the growing season. These tomato plants are growing in a wooden mandarin orange crate.

We grow tomato seeds indoors to get a head start on the growing season. That head start gives us an earlier harvest.

When it comes to timing, the date of the last spring frost is our guidepost. You’ll often see this date called the “last frost date” or “average last frost date.”

Find out the average last frost date for your area, and then count backwards 6 to 8 weeks.

For example:

The average last frost date around here is mid May. So working backwards 8 weeks, I know that I should be starting tomato seeds indoors around mid March.

This is not an exact science.

So don’t sweat the exact date.

Aim for approximately 6-8 weeks. But don’t start too early, because you could end up with leggy seedlings.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Supplies for Growing Tomato Seeds Indoors

The supplies you need when growing tomatoes from seed depends on your approach to gardening. As I mentioned above, you can keep it pretty simple.

Cell packs are a good option if you’re growing a lot of seedlings.

Here are basic supplies:

Potting soil

Pots or containers (ideas below)

Labels

Seeds

Optional goodies:

Heat mat

Fan

Dome or cover

Containers for Starting Tomato Seeds

You can buy purpose-made containers for starting seeds. Or you might already have things you can reuse for seed-starting. (Horticulture creates a lot of plastic waste…and a bit of creativity with seed-starting containers is a great way to generate less waste.)

Here are ideas for seed-starting containers for tomatoes:

Plug trays are an option if you want to start lots of seeds.

Cell packs. These are the plastic containers with multiple holes, often used for bedding plants – a good option if you’re growing a lot of seedlings.

Plug trays. Plastic trays with a number of smaller holes, more commonly used in commercial greenhouses.

Pots.

Crates. I’ve used wooden mandarin orange crates.

Newspaper pots. Remember that paper pots wick moisture and dry quickly, so adjust your watering accordingly.

Egg cartons. Like egg shells, below, too small for growing tomato plants to the final transplanting size, but if it’s all you have, they’re OK for getting seeds started before transplanting into a bigger pot.

Egg shells? Don’t bother. There are lots of cutesy pictures online of seeds growing in egg shells. My suggestion is don’t bother, they’re impractical.

Newspaper pots are easy to make. They can be planted directly into the garden as the roots grow right through the newspaper.

If you’re using biodegradable, natural-fibre pots (peat pots are common, and I’ve even seen pots made from cow manure) a word of caution: Bury the entire pot when planting in the garden, or the whole thing is a wick, wicking water away from plant roots.

Soil for Starting Tomato Seeds

Top Tip: Don’t use garden soil.

That’s for two reasons: First, many garden soils have a structure that packs down, preventing little roots from growing. The other thing is that garden soil can harbour diseases that kill young tomato seedlings.

Use potting soil.

You might see potting soils specifically for seed-starting. These are made with ingredients that are more finely ground, so that there are no chunks of material blocking the way of little germinating seeds.

You don’t need the finely ground potting soils.

A general-purpose potting soil is fine. (A finely ground seed-starting mix is important for commercial growers who need uniform, optimal seed germination; but in a home garden we usually have more seeds than we need, so having the odd coarse chunk in the soil is no big deal).

If the soil is dry, moisten it before using it.

Light for Your Tomato Seedlings

Grow lights for growing tomato seedlings. I use fluorescent lights. Note that the trays are propped up to be as close as possible to the lights.

Good light is important for growing compact plants. When there’s not enough light you end up with leggy plants that topple over.

There are lots of lighting options. The simplest and least expensive is to grow seedlings in a bright window (south facing is best.)

If you don’t have a bright window, you can start seeds under lights. There are many types of lights available.

Here’s the thing to know: Your tomato seedlings don’t need the same light as an indoor hydroponic vegetable crop.

You’re not trying to create perfect conditions to grow a plant right through to harvest. The lights just need to be good enough to give you healthy, fairly compact tomato transplants.

So save yourself some money and don’t go overboard on lighting.

My lighting for growing tomato seedlings is fluorescent shop lights. You don’t need full spectrum lights, nor do you need the strongest lights. Remember: You’re growing a young plant to transplant outdoors – where it will spend the rest of its life in sunlight.

Some grow light are adjustable, allowing you to move the lights close to the seedlings. Mine aren’t, so instead, I prop up trays of plants closer to the lights by putting something underneath them.

Use a timer so that you don’t have to remember to turn the grow lights on and off every day. I leave mine on for 16 hours a day.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Planting Tomato Seeds

Fill your container with soil, leaving a bit of space at the top.

If you’re planting an individual seed, place it on top of the soil

If you’re planting a number of seeds in one container, space them out on top of the soil

Then place a thin layer of soil over the top. You don’t need to put much soil over the seed: Cover with a depth of soil similar to the seed width…up to about one-quarter inch. (Too deep and they might not grow.)

Then tamp very gently and water. What we’re trying to do by covering with soil and tamping is to make sure the seed is in contact with soil, which helps with uniform germination.

Wait a minute. Have you seen the recommendation to make a small hole, put a seed in the hole, and then cover with soil? There’s a gizmo called a dibbler that’s used to make holes. And some gardeners make holes, and even use a toothpick for precise seed placement. That’s fine too. There are many ways to plant tomatoes. My opinion is that this sort of precision is needed in a commercial operation…but I don’t need it for at the home-garden level.

Tomato Seeding Density

Not sure how many seeds to put in each container? Depending on how many tomato plants you’re growing and how much space you have, you can seed more or less densely:

Grow 2-3 seeds per pot, and then thin out extras as the tomato plants begin to grow.

Low Density

If you have lots of space and aren’t growing a lot, give each seed its own pot or section within a cell pack. One seed per pot takes up far more space initially. But if you want to keep things very simple, this is a good way to do it because it can cut out the step of transplanting later on.

Remember that a bigger pot dries out more slowly; water them accordingly so they aren’t waterlogged.

Tip: It’s rare to have every single seed germinate. To avoid having empty pots where seeds haven’t germinated, place 2-3 seeds per pot, and then thin out extras as the plants begin to grow.

High Density

If you want to start more seeds in less space, plant more than one seed in a container, and then separate and transplant them as they get bigger.

Labelling

A tray of labelled tomato seedlings.

If you’re growing more than one variety, label them as you plant them. There are years I was sure I’d remember what was what…and I forgot.

You can use purpose-made plastic labels; or, if you want to use less plastic, wooden popsickle sticks or wooden tongue depressors work well (but don’t last all summer.)

If you’re using pots or cell packs, you can also just write the tomato variety name on masking tape, and then stick it on the container.

Hygiene

Damping off disease can wipe out a whole crop of seedlings quickly. It’s a fungal disease that moves around your growing area along with runoff from watering plants. It gets there in contaminated soil and on previously used equipment and pots.

The easiest way to avoid damping off is to use disease-free soil and clean supplies. If you make your own potting soil using compost, consider sterilizing it. Many commercial potting soils are made with peat and inert ingredients—and these tend to be disease free.

New pots and cell packs are likely disease free, but if you’re reusing pots and cell packs, sterilize them. First, scrub off any soil that’s caked on. Then dunk them in a solution of 10 parts water with 1 part bleach, and then let them air dry. (Note: This is a strong smelling solution, so I do this outdoors or in my garage.)

How Many Seeds to Grow

Planting extra tomato seeds is cheap insurance against plants lost to accidents.

I always grow extra plants.

Then I share leftovers with friends.

Conditions for Germinating Tomato Seed

Temperature

No heat mat? No problem. Find a warm spot to germinate tomato seeds. Pictured here: Germinating a flat of tomato seeds beside a heat duct near the basement ceiling — a warm location. (The wine is unrelated…I didn’t have a lot of space in that house!)

Room temperature is fine for germinating tomato seeds, but you can speed up seed germination if the temperature is warmer.

Here are ways to give your seeds warmer conditions:

Place them on a heated floor

Set them on top of a hot-water radiator

The fluorescent fixtures in my light tray give off heat, so if I put seed containers on the rack above

Some appliances give off heat – check to see if the top of your fridge is warm

Or get a heat mat (a water-resistant heating pad for plants)

Once a half to three quarters of the seeds are up, I remove the container from the heat.

Humidity

As a seed germinates, it needs moist surroundings until it grows roots and can take up water on its own. If it dries out at this vulnerable stage, it’s game over.

But the air in centrally heated homes over the winter is often quite dry.

You can keep the humidity higher right around the seeds by covering them.

I use the clear plastic domes designed to go over top of plant trays.

Or, cover a tray with a sheet of glass or plastic; or cover an individual pot with a plastic bag.

Another option is to use plastic cling wrap

Remove once the seeds emerge.

Light

Don’t worry about light for tomato seed germination. Some types of seed need light to germinate; not tomatoes.

The seedlings on the left are uncovered, to get air circulation. The seeds on the right are covered with a plastic cover to keep the humidity high during germination.

So in summary, as you’re getting your tomato seeds to germinate, think warm and humid. (In a previous house, I’d germinate my seeds atop a shelf in the basement, near the heat duct at ceiling level, where it was nice and warm.)

Conditions for Growing Tomato Seedlings

Once your tomato seedlings are up and growing, the best conditions are different from what we want when germinating seeds.

Light and Temperature

As seedlings begin to grow, we want bright light and cooler temperatures. That’s because with warmer temperatures, growth is lanky. With cooler temperatures (combined with bright light) the plants will be more compact and sturdy.

See if there’s a cooler spot near a sunny window. In my case, my grow lights are in the basement, in a room that is cooler than the rest of the house. It’s perfect for growing tomato seedlings.

Humidity and Air Circulation

High humidity while seed germinate is good.

But as the plants grow, we want lower humidity and some air circulation, which reduces the chance of fugal diseases. The moving air also gives stronger stems. (Some people use a fan to improve air circulation.)

So in summary, once the tomato plants are growing, you want cooler, brighter conditions than for germination.

Caring for Tomato Seedlings

Water

It’s easy to kill seedlings by overwatering them.

Keep the soil moist, but not sopping wet. Moist, but not waterlogged.

If in doubt about the amount of moisture in the soil, use your finger. (Whatever you do, don’t waste your money on a gadget that tells you soil moisture!)

Wondering about bottom watering? A lot of people “bottom water” seedlings. This just means sitting a container in water so that water wicks upwards. The reason is that a strong jet of water from a watering can can move around seeds and soil. So feel free to do the bottom watering if you like, although I find that watering gently, by putting my finger over the tip of the watering can to slow the flow of water, is enough to prevent making a potting soil sinkhole.

(If you forget to water and your seedlings flop over, there might still be hope. I remember the seedlings I grew with Dido: we came home one day and they were flopped right over…looked like they were doing yoga. He shrugged and watered them—and they sprang back up within an hour.)

Feeding Tomato Seedlings

Check your potting soil mix to see if it contains fertilizer. Some do. And if it contains fertilizer, you might not need to feed.

Otherwise, once your plants have a few leaves, you can begin to feed them. I use a water-soluble fertilizer.

Don’t overfeed. It can damage delicate seedling roots. (I feed at half of the rate recommended on the label.)

Transplant tomato seedlings after they get “true leaves,” the second set of leaves that comes after the “seed leaves.” These plants are beginning to grow true leaves.

Note: Don’t worry about feeding before the seedlings have a couple of sets of leaves. They’re still drawing from stored energy in the seed.

Thinning and Repotting

If you planted a few seeds together in a container, once they get big enough to handle, you can separate them and give them more space.

If you planted a few seeds together in a container, once they get big enough to handle, you can separate them and give them more space.

Transplant tomato seedlings after they get “true leaves.” The first leaves that appear are “seed leaves” so it’s the third and fourth leaves that are the true leaves. You’ll quickly see the difference.

I use a popsicle stick or pencil to tease apart soil and gently lift up a seedling and its roots. (There are purpose-made gadgets for this…not necessary.)

When picking up seedlings, hold them by the leaves. That’s because it’s very easy to crush the stem. (If you crush a leaf, it can grow a new leaf…if you crush the stem, it’s game over.)

Transplanting Tomato Plants in the Garden

Moving tomato seedlings outdoors to a cold frame in the spring so that they are hardened off for planting into the garden. If the light is bright, we cover the top of the cold frame with something to shade the plants below.

When it’s time to move your tomato seedlings to the garden, there’s one last thing to remember: Your seedlings have grown in the house, in moderate conditions. Once they’re outdoors, the light is brighter, the temperature swings, and there’s wind.

So we “harden off” seedlings, which simply means we get them used to outdoor conditions.

We do this by putting the plants outdoors, in the shade, for a few hours each day. Give them a longer stint in the sun each day, and keep doing this for at least a week.

Got lanky tomato plants? If you have lanky plants, with more stem than you want, you can bury a lot of that stem. That’s because tomato plants will send out new roots where you bury the stem. So just dig a deep hole, or make a trench and lay the plant on its side.

FAQ - How to Grow Tomato Seeds

Can I plant tomato seeds directly in the garden?

Yes, but your harvest will be weeks behind plants started indoors. (Tomato plants sometimes come up on their own in the garden where tomatoes fell to the ground the previous year…but the harvest is late.)

Should I soak my tomato seeds?

No, it’s not necessary.

Can I save my own seed?

Absolutely. It can be as simple as smearing some seeds on a paper towel, or you can clean them more through a fermentation process. In our household, I do the former, while my daughter does the latter.

Note: If you save seeds from hybrid tomato varieties, the seeds you end up with will be different from the parent plant. If you plan to save seeds, look for “open pollinated” varieties.

Is it too late if I start my tomato seeds only 4 weeks before the last frost?

No, but your harvest won’t be as early.

Can I start my tomato plants 10 weeks before the last frost?

Yes, but when they’re started indoors early, there’s more chance of ending up with lanky plants, unless you have very good growing conditions. If I had a greenhouse, I’d consider starting a few plants earlier—for an earlier harvest.

Where can I find the average last frost date for my area?

The easiest way is to do an online search. Some seed companies list dates, as do some master gardener groups and extension agencies.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More About Growing Tomatoes

Hear Tips from Tomato Experts

Course: Tomato Overload Masterclass

Want to up your game growing tomatoes?

This self-paced course helps you choose great varieties, grow great seedlings, give plants the care they need, and enjoy an abundant harvest.

Find Exotic Edible Plants for Your Garden

Find out where to buy a lemon tree.

By Steven Biggs

Looking for Exotic Edibles for Your Home Garden?

I get a lot of messages from people who are eager to grow a new exotic edible crop…but are not sure where to find it. I hope this list of plants suppliers helps you find what you’re looking for.

This list focuses on nurseries, garden centres, and other plant suppliers in Canada and the northern USA.

It’s a work in progress. If you know a supplier that should be on this list, e-mail me to let me know.

Get started with some shopping tips, below.

Tips When Shopping for Exotic Edible Plants

Here are tips to keep in mind as you get ready to shop for plants.

Delivery vs. Pick-Up

Large potted plants are expensive to ship! Delivery costs depend on the distance and the size of the plant.

If pick-up is an option, you might save money.

Mail-order sellers usually only ship spring through fall, when the temperature is warm enough.

Seasonal Exotic Plant Availability

Some of these plant sellers are nurseries that propagate their own plants and have plants year-round.

Others are garden centres that carry less common plants seasonally.

For example, here in Southern Ontario, I often start to see California-grown potted citrus trees in garden centres in the spring. Then, selection usually declines through the season, and once they’re sold out, that’s it until the following year.

Cross-Border Shipments

Some nurseries and garden centres don’t ship plants out of country. That’s because sending plants across the border involves a lot of paperwork.

If you find an out-of-country vendor who does ship to your area, ask about any additional cost for inspections and paperwork. And check about the delay that inspections can cause for your order.

Canada Exotic Edibles

Looking for Canadian nurseries that sell exotic plants? Here’s a list of Canadian retailers of exotic plants. Remember: Not all nurseries grow their own plants. So if you want plants produced in Canada, ask the retailer.

Angelo’s Garden Centre

Vaughan, Ontario

This is a garden centre near me, in the Toronto area, that seasonally carries citrus trees, olive trees, and fig trees. (I got my first olive tree here!) Hear owner Carlo Amendolia tell the story of their 19-foot-high fig tree.

Brugmansia Quebec

St-Valérien de Milton, Québec

A good selection of citrus trees, figs, and, as the name suggests, Brugmansia—a.k.a. angel’s trumpet.

Exotic Fruit Nursery

Lunenburg, Nova Scotia

Citrus trees, hardy fruit trees, exotic fruit, and nut trees.

Fiesta Gardens

Toronto, Ontario

We’re big fans of Fiesta Gardens, here in Toronto. This independent garden centre brings in some really cool plant material every year—and there are usually lemon trees and other citrus too.

Flora Exotica

Montreal, Quebec

Exotic plants and seeds. Lots of unusual fruit.

Fruit Trees and More

North Saanich, British Columbia

This nursery and demonstration orchard specializes in plants for Mediterranean climates. Owner Bob Duncan was the inspiration for my book Grow Lemons Where You Think You Can’t. He grow citrus tree espaliers in his demonstration orchard, and has a big Meyer lemon espalier on his house.

Nutcracker Nursery

Maskinongé, Quebec

Nice selection of citrus trees and figs. As the name suggests, they specialize in nuts. Also other fruit (I’ve ordered plums and damsons here and was pleased with the quality of the plants.)

Phoenix Perennials

Richmond, British Columbia

An excellent mail-order nursery with unusual plants. (This is where I tracked down a grafted tomato-potato plant for my daughter!) They have a good selection of citrus trees.

Richters Herbs

Goodwood, Ontario

Both seeds and plants. Greenhouses open to the public, and it’s a fun place to browse. We came home with 19 types of mint after one visit. Lots of figs too.

Sage Garden Greenhouses

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Co-owner Dave Hanson has joined me to teach about exotic edibles and Mediterranean plants. He is a wealth of knowledge.

Tropic of Canada

Rodney, Ontario

Citrus, figs, and a fun mix of exotics.

Valleyview Gardens

Markham, Ontario

This Toronto-area garden centre has tropical plants year-round. When I couldn’t find a yuzu citrus tree, this is where I found one.

USA Exotic Edibles

Edible Landscaping

Afton, Virginia

Citrus, fruit trees, fruit bushes, berries, and exotics.

Four Winds Growers

Winters, California

Specializes in semi-dwarf citrus trees.

Logee’s

Danielson, Connecticut

As well as citrus, they have figs and other exotic fruit—and a ton of ornamentals. Their ponderosa lemon is over 100 years old!

McKenzie Farm

Scranton, South Carolina

Owner Stan McKenzie is passionate about cold-hardy citrus. Hear Stan tell us all about cold-hardy citrus on The Food Garden Life Show.

One Green World

Portland, Oregon

A delicious mix of citrus trees, olives, figs, and lots of sub-tropical fruit.

Sam Hubert from One Green World joined us on the Food Garden Life show with top cold-hardy citrus picks. Find out Sam’s favourite cold-hardy citrus.

Well-Sweep Herb Farm

Port Murray, New Jersey

Lots of herbs, and a good selection of citrus.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

Find Out How to Grow Exotic Edibles

More Sources for Plants

Potting Soils: Choose the Right Potting Soil

A good potting soil helps your container vegetable garden thrive!

By Steven Biggs

Choose the Best Potting Mix

Ever had potted plants that just seem to stall?

It could be the soil.

Good potting soil can be the difference between potted crops that grow like gangbusters...and those that don't seem to do anything.

This guide covers key soil ingredients, types of soil mixes, and tips to help you choose good soil. If you're a home gardener who wants to keep things simple but use the best soil mix, keep reading.

Key Takeaways

Potting soil is a soil blend made for the growing conditions in containers.

Despite the name, it often contains no garden soil.

Common potting soil ingredients include peat moss, compost, coir, perlite, and vermiculite.

There are specialty potting soils for specific plants and purposes.

You can buy ready-made potting soil or blend your own.

Understanding Potting Soil

Potting Mix vs. Potting Soil

Potting mix is made for the growing conditions in containers. Many have no soil. This mix has peat moss and perlite.

You might come across a few different names used for potting soil, including potting mix, growing medium (if you're reading technical sources), potting medium, soilless medium, and soilless mix. In British English, you'll also find term "compost" used for potting soil.

In a Nutshell

Potting soil is a soil mix made for plants in containers. Because the roots of plants in containers can't spread out to find water, moisture retention is important.

But even though we need the soil to hold moisture, we also need lots of little air pockets. That's called "aeration." Those little air pockets helps excess water move through the soil, while also leaving space for the soil to hold on to some of the water, until the plant roots can absorb it.

Some potting soil mixes—though not all—contain food for the plants. It could be in the form of a separate fertilizing product. But it might also come from one of the soil ingredients.

In short, a good potting mix retains moisture...yet drains well. It doesn't pack down with repeated watering.

Potting Soil vs. Garden Soil

Soil from the garden is rarely ideal for potted plants. That's because it often packs down with the frequent watering.

Garden soil can also contain weed seeds and diseases.

Key Ingredients in Potting Soil

Ask 10 gardeners for soil-mix recipes and you might come away with 10 different recipes. Like most things in life, there's more than one way to go about it.

But there are some ingredients that are frequently used to make commercial potting mixes. We'll look at some of them below.

Organic Ingredients

By "organic" we just mean something that was once living. Organic ingredients include peat moss, coir, compost, and composted bark chips.

Maybe before we even jump into these organic ingredients, let's not ignore the elephant in the room. There's an environmental footprint to potting soils. Peat moss is extracted from peat bogs, where carbon has been sequestered long-term. When we use peat moss for gardening, that carbon is quickly released back into the environment. Coir is touted an environmentally preferable substitute, though it's from a crop planted where there were once rain forests...and then it's shipped a long ways for a northern gardener like me.

If this environmental footprint is on your mind, here are some thoughts:

Don't waste potting soil—and certainly don't use it like a garden-soil amendment

Use your potting soil for more than a year where appropriate

Consider potting-soil ingredients such as home-made compost and composted forestry waste

Peat Moss

Peat moss is widely used because it holds water really well—like a sponge. Yet it still drains well. Lots of air pockets, yet still moisture that plant roots can take up.

When peat moss gets very dry, it repels water. (It becomes "hydrophobic" if you like the technical jargon.) So if you're mixing your own soil, moisten the peat moss beforehand. (Commercially prepared soil mixes often have an ingredient called a "wetting agent" that makes the peat less hydrophobic.)

Because peat moss is acidic, ground limestone is often added to peat-based potting soils. This helps to balance the pH. (And that's important because if the soil is too acidic, plants might not be able to take up the nutrients they need.)

Coir

Coconut coir is commonly used as an alternative to peat moss. We're talking about the fibre from coconut husks. As well as being used in place of peat moss, some gardeners blend coir with peat moss.

Coir-based soil mixes are sold in bags, as are peat-based soil mixes. But you can also find compressed bricks of coir. They're completely dry and very lightweight. These bricks are soaked in water before making a potting mix.

Compost

Here’s a close up of a potted bulb growing in a soilless coir mix. You can see the long fibres.

The nutrient content of a compost depends on what it's made from. For example, composted animal manures or composted seafood waste contain higher nutrient levels that something such as composted leaves (a.k.a. leaf mould.)

If you’re aiming to make your own peat-free soil mixes, leaf mould (composted leaves) is a traditional ingredient. Leaf mould breaks down more quickly than coir and peat.

Composted Bark Chips

Composted bark chips are sometimes added to soil mixes for larger plants. The bark bulks out the soil mix, while holding moisture.

Worm Castings

Worm castings—worm poo—add nutrients and microbial activity to a soil mix.

Inorganic Ingredients

With inorganic ingredient, we're mainly talking about "aggregates," things that add structure to the potting soil. These include perlite, vermiculite, sand, and grit. Light-weight materials such as perlite and vermiculite are common in commercially prepared soilless potting mixes.

Perlite

This popcorn-like, light, fluffy material is heat-expanded volcanic glass. It adds air pockets to the potting soil.

Vermiculite

Vermiculite is heat-expanded mica. It's like a sponge, able to hold water and nutrients. Because it’s so good at holding moisture, the soil is less likely to shrink when dry.

Sand

Common in home-made soil mixes to improve drainage and to add weight. Not so common in commercial mixes because it adds weight...and that makes shipping more expensive.

Vermiculite helps to retain moisture.

Perlite adds lots of air pockets to a mix.

Types of Potting Soils

Potting soil can be blended for specific types of plants (e.g. cactus), for certain plant needs (e.g. acid-loving plants, or "high porosity" for plants that don't like wet roots), and for specific uses, such as seed-starting.

Here are common types of ready-to-go potting soils:

All-Purpose Potting Mix

This high-porosity potting mix is made from peat and perlite.

As the name suggests, this sort of mix is intended for a wide range of uses and plants. Many commercial all-purpose blends (I've seen the name "general-purpose" used too) contain peat moss or coir, compost, vermiculite, and perlite.

High-Porosity Mixes

High porosity is just another way of saying it drains well.

This sort of mix is for plants that don't do well when the roots remain wet for too long. For example, if you're growing a potted lemon tree, good drainage is very important because the roots can quickly rot if the soil stays wet for too long.

(An interesting aside: I asked at my local garden centre why they're now stocking this sort of mix, which I only used to see in commercial horticulture. I was amused to learn that home cannabis growers favour it!)

"Organic" Potting Mix

It's worth mentioning that some companies market "organic" soils. These will contain the organic portion we talk about above (peat, coir, compost, etc.) meaning something that was once living.

But in this case, the word "organic" has an additional meaning: It means that the mix meets the standards of an organic certification organization. And that usually means that there's no wetting agents (something that makes the peat moss easier to wet) and that if there are fertilizers in the potting mix, they're approved by the certifying agency.

Seed-Starting Mix

The main difference with seed-starting mixes is that the texture is finer. Smaller vermiculite. No coarse bits in the peat moss. Perhaps no perlite. The idea is that a small, germinating seed isn't blocked by a hunk of something in your soil mix.

For what it's worth, I don't buy seedling mixes. They make sense for a commercial grower striving for a very high rate of success and uniformity. In my case, I always have ample seed for my smallish garden, so if the odd seed conks out because I'm using a general purpose mix and it's blocked by a big piece of perlite, it doesn't matter a bit.

Some people use an all-purpose mix, and simply screen out large bits, or break up the large bits while planting.

Homemade Potting Soil

What's the best potting soil? As I mention above, you're likely to find many different recipes for homemade potting mixes. The best mix depends on what you're growing, the growing conditions—and how you water! (I've met gardeners who know they're heavy handed with watering, so they blend especially well draining soilless potting mixes for their plants that don't tolerate wet roots.

If you don't need a lot of soil, you might find it easier just to use an off-the-shelf soil. But if you use quite a bit of soil, or if you have certain requirements, then making your own potting soil allows you to customize the ingredients and match them to the needs of your plants.

General-Purpose Soilless Mix Recipe

When it comes to general-purpose mixes, I keep my life simple, and just use an off-the-shelf product.

If you prefer to mix your own, here's a simple recipe you can start with:

2 parts peat moss (or peat moss substitute such as coir)

1 part vermiculite

1 part perlite

If you're using peat moss, add ground limestone so that the mix is less acidic. Add 30 ml of limestone for a 10 litre pail of soil.

One other tip: If the peat or coir is very dry, wet it first, before mixing with the other ingredients.

And one more tip: Using peat? Get "horticultural" or "blond" peat. Peat at the bottom of a peat bog has decomposed more, so it has shorter fibres. Because of the shorter fibres, it packs down more quickly. The peat that’s higher up in the bog has a lighter colour and longer fibres. It’s called “blond” peat. The blond peat is what you want because it gives a soil with more air pores, but at the same time, it holds water well.

It’s usually the dark peat that I see for sale at garden centres around here—because it’s less expensive and many people don't know the difference.

Container Veg Gardening Course

Soil-based Potting Mix

I use a soil-based potting mix for larger outdoor potted plants. Here's my mix for growing potted fig trees. It's good for all sorts of other potted plants too. With the garden-soil component, this mix holds more moisture. And the garden soil and sand both make it heavier, so that large plants are less likely to topple in the wind.

1 part garden loam

2 parts soilless potting mix (I prefer a commercial-grade of soilless potting mix, see my tips on soil-shopping, below)

1 part sand

Add 30 ml of limestone for a 10 litre pail of the mix

If you want to read more about potting soil for fig trees, here are my recommendations for potting soil for fig trees in pots.

Shopping for Potting Soil

It’s buyer beware when it comes to small, domestic-sized bags of potting mix. Some is great…some is terrible.

A simple approach that I recommend to all my students is to buy potting soil mixed for commercial producers. The quality is consistently good. Which makes sense, because commercial growers know good soil and won't settle for less.

Commercial potting mix is sold in "bales" that are 107 litres (3.8 cubic feet). And the soil within is dry and compressed. So it's a fair bit of soil, but I think it's worth it.

Summary

Good potting mix is a key to success with container gardening. There are many special-purpose mixes available. In many cases, a general purpose mix works quite well. If it's an option, buy a large, commercial-sized bag; the quality is more consistent. When mixing your own potting soil, remember that there are many recipes--and that what's the best for you depends on how you water and what you're growing.

If you’re interested in potting soil because you’re growing vegetables in containers, grab this container veggie guide.

Frequently Asked Questions

Pin this post!

What are the key ingredients in a good potting soil?

A potting soil has an organic component such as peat moss, coir, or compost. This is bulked out with an aggregate such as perlite, vermiculite, or sand.

Can I reuse old potting soil?