Guide: How to Grow Ground Cherries and Cape Gooseberries

Guide: How to grow ground cherries and cape gooseberries

By Steven Biggs

Unhusking the Husk Cherries

Looking for an easy-to-grow fruit for a northern garden?

Here are a couple of sweet, tangy annual fruit crops that are a snap to grow. They're great for container gardens too.

As you peel back the papery husk, inside you find a round, shiny yellow- or orange-coloured fruit.

(The whole business of peeling back the husk makes them very fun for kids...and adults too!)

In this article we take a look at the ground cherry (Physalis pruinosa) and its lesser known cousin, the cape gooseberry (Physalis peruviana). They're both part of the nightshade clan—in the same plant family as tomatoes, peppers, tomatilloes, potatoes, and eggplants.

But they don't taste a bit like epplant or pepper, as you'll read below.

Ground Cherries

Ground cherry plants are fast-growing and sprawling, with small yellow-and-black flowers. They're probably the easiest to grow out of the nightshade clan.

A ground cherry plant will grow up to about one metre (3') high.

The taste of the berry is sweet and fruity. Some people liken them to pineapple.

Ground cherries are called by a few different names, including husk tomato, husk cherry, strawberry tomato, and golden cherry.

Cape Gooseberries

While it's not related to the true gooseberry, the tanginess of the cape gooseberry might account for it borrowing the name.

I've also seen this fruit called by other names including golden berry, goldenberry, physalis, and Peruvian groundcherry.

Growing cape gooseberry is worth the extra wait. The fruit is slightly larger, more citrusy, and a darker colour than ground cherry fruit.

Cape gooseberry plants are larger and more upright than ground cherry plants, getting up to about 1 ½ metres (4-5') tall. The fruit is slightly larger, citrusy, and a darker colour than ground cherry fruit.

Out of the two husk cherries, I prefer cape gooseberry.

But...there's a tradeoff: It takes longer to mature. As I explain below, there are a couple of things you can do to get cape gooseberries to mature more quickly in a northern garden.

(Cape gooseberry is a perennial in warmer climates...but we grow it as an annual in northern gardens.)

How to Grow Ground Cherries and Grow Cape Gooseberries

Both of these fruits are grown as annual crops in cooler climates. They're a good fit for the veggie garden or a container garden.

To get fruit as early as possible, start seeds indoors.

Start Ground Cherry and Cape Gooseberry Seed Indoors

A tray of ground cherry seedlings. Grow ground cherry and cape gooseberry seeds the same way as tomato seeds.

Treat ground cherry seeds and cape gooseberry seeds the same as you would tomato seeds.

That means:

Plant seeds 6-8 weeks before the average last frost date for your area

Plant cape gooseberry seeds earlier, as plants are slower to mature in cold climates (I aim for 8 weeks with mine, while I plant ground cherries about 6 weeks before the last frost)

Heat from below helps to speed up germination (a heat mat, or placing seed trays on a heated floor or radiator)

One other thing to think about:

Both of these crops self-sow, meaning that fallen fruit that you don't pick up gives you lots of little "volunteer" plants the following year.

Because ground cherries grow fairly quickly, I often let some of these little ground cherry plants grow. They fruit later than my transplants, but are still worth the space. But don't bother with volunteer cape gooseberry plants in a northern garden...they need too long a season.

Grow Ground Cherry Seeds

Ground cherry with the husk peeled back. They make a great garnish!

There are a few varieties of ground cherry seeds available.

Common ground cherry varieties include:

Aunt Molly’s

Cossack Pineapple

Golden Husk

There are also lots of unnamed ground cherry seeds for sale.

When it comes to cape gooseberry, I've never seen any named varieties.

Transplanting Ground Cherry and Cape Gooseberry Seedlings

Time your transplanting as you would for tomatoes.

You can transplant ground cherry and cape gooseberry seedlings into the garden when there is no longer any danger of frost and the daytime temperature is warm. I aim for 15-20°C (60-68°F).

If you've already transplanted your seedlings and the temperature dips, place floating row covers over them to keep them a bit warmer.

And don't forget the soil temperature: Cool soil sends them into a tizzy. If it's been a late spring, and the air is warm but the soil hasn't had time to warm up, it won't hurt to wait a bit before planting them.

Choose a Location

Ground cherries and cape gooseberries grow well in a wide variety of soil types.

Avoid very heavy and wet soils.

A raised bed is a great option for the cape gooseberry plant. That's because the soil in raised beds heats up more quickly in the spring—and that extra soil heat is helpful in a short season.

How to Plant Ground Cherries

When planting outdoors in the garden, space ground cherries and cape gooseberries about 60 cm (2') apart.

As you transplant seedlings, keep the soil level the same—don't bury the stem as is commonly done with tomatoes. That's because ground cherries and cape gooseberries don't root as readily from the stem as tomato plants do.

And here's something you'll be glad you did once harvest time rolls around: Mulch around the plants so that fruit that falls to the ground stays clean.

Growing Ground Cherries

Because cape gooseberry plants have a more upright growth, they benefit from a tall cage.

With their squat growth, ground cherries don't need any support or special training.

If you want, you can keep the plant a little bit more upright using a cage—but there's really no need.

Growing Cape Gooseberries

Because a cape gooseberry bush has a more upright growth, it benefits from a tall cage—or even from staking so that it doesn’t bend over on a windy day.

How to Grow Ground Cherries in Containers

Grow cape gooseberry and ground cherry in containers for an earlier harvest.

Container growing has two advantages in a home garden:

Warm Soil: The soil in containers heats up faster than the soil in the garden

Heat: You can situate containers for maximum heat and sunlight to speed up harvest (e.g. next to a warm wall or on a warm driveway)

Cape gooseberry plants benefit from extra heat in cool climates with a short season. This black sub-irrigated container has warm soil, and gives constant soil moisture.

Consistent soil moisture, warm soil, and well-fed soil give the best results.

To maintain soil moisture, consider a sub-irrigated pot (self-watering pot.)

Find out how to make your own sub-irrigated pot.

Harvesting Ground Cherries and Cape Gooseberries

The papery husk turns from green to a tan colour as the fruit inside ripens. The colour of the ripe fruit depends on the variety, ranging from light yellow through to a pale orange.

Ripe ground cherries drop off the plant; ripe cape gooseberries remain on the plant.

If the fruit is still green, it's unripe. Don't eat it. That's because, like it's nightshade kin, the stems, leaves, and unripe fruit contain things that can upset your stomach.

Don’t eat green fruit, they contain toxins that cause stomach upset.

If you leave fallen ground cherries on the ground for a while, sometimes all that remains of the papery ground cherry husks is a fine netting—and you can see the golden fruit inside.

Store Ground Cherries and Cape Gooseberries

Plants continue to grow and flower all season long. So when the first fall frost threatens, you'll have green, unripe ground cherries and cape gooseberries.

Pick these green fruit and let them ripen indoors. When spread out to ripen, many of them will ripen. I put mine on a tray, in a cool room in my basement and enjoy them for weeks after the first fall frost.

Save Ground Cherry Seeds

Each ground cherry fruit is full of many small seeds.

Save and dry ground cherry seed for for the following year. They can stay viable for a few years.

I simply smear some of the seed-filled flesh onto a paper towel. Once it's dry, I put it into an envelope and label it.

Save cape gooseberry seeds in exactly the same way.

Eating Ground Cherries and Cape Gooseberries

Emma shows off a ground-cherry-blueberry crostata she made.

I was once in the Lac St-Jean region of Quebec and found locally made ground cherry liqueur. It was divine—a rich yellow colour, both sweet and tangy.

Fresh ground cherries and cape gooseberries are so tasty that we don't often have a lot left for other uses.

Wondering how to eat ground cherries? There's lots you can do with them:

Ground cherries as garnishes (peel back that papery husk and they look quite attractive!)

Ground cherry jam

Ground cherry cobbler

Ground cherry crostata

Dried ground cherries

Ground Cherry Pests

Three-lined potato beetle larvae enjoying cape gooseberry leaves. Easy to solve with soapy water.

Ground cherries and cape gooseberries are about as trouble-free a crop as you'll get.

If you have a problem, the most common is one of the pests that go after other nightshade crops. They include:

Tomato hornworms

Cutworms

Colorado potato beetle

Three-lined potato beetle

In a home garden, hand pick hornworms and colorado potato beetles. When three-lined potato beetle larvae start making holes in my cape gooseberry leaves, a soapy-water treatment solves the problem.

Prevent cutworm damage by using a newspaper collar around young plants as you transplant them into the garden.

One year a raccoon took a shine to my cape gooseberries...and I'd find empty husks on the ground around the cape gooseberry plants. Toronto has an unusually high density of raccoons, so I don't expect this will be an issue for most people. If it is, a simple solution is to physically exclude the raccoons. Cage the plants. It's what we do with our melons.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

FAQ

Can you grow ground cherries indoors?

There is no need to grow your ground cherry plants indoors, even in a northern climate. That's because you can get a sizeable harvest even where there's a short growing season.

These are nicely branched ground cherry plants. They can get up to about one metre high.

If you really want to grow them indoors (I've never tried) the key would be a light setup suitable for indoor growing. A windowsill over the winter would not be bright enough.

Do ground cherries grow back every year?

The plants die over the winter, but ground cherries often "volunteer," which means new plants grow from seeds left over from prior years.

Are tomatillos and ground cherries the same thing?

No.

Tomatillos (a.k.a. husk tomatoes) produce larger fruit than ground cherries. And unlike ground cherries, the fruit completely fills its husk at maturity, and actually bursts open. While ground cherries are consumed as a sweet, tomatillos are usually picked green for use in savoury dishes.

How many ground cherries do you get per plant?

More than you can count!

How do you overwinter ground cherries?

You don't. Start new plants each spring.

Do ground cherries ripen after picking?

Yes. As the first fall frost approaches, pick green cherries that are almost full size but still green. They will continue to ripen.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More Information About Growing Fruit

Articles

Browse our articles about growing fruit.

Guide to Growing Saskatoon Berries: Planting, Pruning, Care

Courses

Want to Water Less and Harvest More? Try Sub-Irrigated Planters

Find out how to make your own sub-irrigated planter (a.k.a. self-watering container).

By Steven Biggs

Wilted by Noon

When I first started container gardening on my garage rooftop, I watered every morning. But in the heat of summer, my plants were parched and wilting by noon.

A sub-irrigated planter is an excellent way to solve the problem of parched plants. We want to prevent wilting, because it’s a sign of stress. Drying out is a stress for the crop.

And that stress can delay (or reduce!) your harvest.

Consistent soil moisture is best. Not sopping wet. Not dry.

And that’s where a sub-irrigated planter helps: It keeps the potting mix consistently moist, but not too wet.

This sort of planter is also known as a SIP, a self-watering container, or a self-watering planter.

Keep reading and I’ll explain how a self-watering system works and how you can make your own.

What are Sub-Irrigated Planters?

Sub-irrigation planters are simply planters with a water reservoir at the bottom. The reservoir is right under the soil.

Through capillary action, water wicks up through the potting mix, giving plant roots a consistent supply of moisture. Then, as the plants use water in the soil (creating a moisture gradient) more water wicks upwards from the reservoir.

There are many commercially produced sub-irrigated planters available. Some are fairly basic and resemble a normal container. Others have a gauge that shows the water level in the reservoir.

Self-Watering Planters vs. SIPS vs. Sub-Irrigation Planters

These are all different terms used to describe the same thing: Containers that have a water reservoir below, so that moisture can wick up into the soil.

By the way, they are not truly “self-watering.” The gardener must still fill the reservoir. (If you like do-it-yourself projects, you can automate this with irrigation, see below.)

Benefits of Sub-Irrigated Planters

Pin this post!

First, though, let’s look at the benefits of these self-watering containers.

Less waste:

There is less waste of water and fertilizer because it's a closed system, with less runoff

Higher yield because:

A continuously moist growing medium means the plant has no water stress (plant growth can slow, or flowers drop when the plant is under stress…)

When gardening in a container, the growing medium is warmer than soil in the garden, and that means that harvest begins earlier

Fewer weeds because:

The soil surface is not regularly moistened from overhead watering, giving dry surface conditions are not as good for weed seeds to germinate

The other reason that the soil surface is not as wet is that the farther you are from the reservoir, the less moist the soil (remember, it's going against gravity!)

Less disease because:

With no overhead watering, there's less splashing of disease organisms from the potting soil onto the leaves

And with tomatoes, SIPS usually solve blossom end rot (which actually is not a disease, but a physiological disorder that's caused by swings in soil moisture)

And the benefit of a SIP system that goes without saying: You spend less time spend watering!

Where to Grow in a Sub-Irrigated Planter

I made a garden on my garage rooftop using sub-irrigated (self-watering) planters.

As with any sort of container garden, a SIP makes it possible to grow on patios, decks, driveways.

You can also use them to grow over top of areas with tree roots or compacted soil.

If you’ve been eyeing up a space next to that water-hungry cedar hedge, this is your solution!

If you’re concerned about soil contamination, making a container garden is a simple solution.

Find out more about soil contamination.

What’s Inside a SIP

Here's what you'll usually find in a self-watering planter.

A water-tight area (the reservoir) at the base of the container (underneath the potting mix)

Something to hold the potting mix above the reservoir area: it could be a false bottom such as mesh, or hollow containers, or tubing

A way to add water to the reservoir (a fill-tube that extends above the soil surface)

A wick (the wick is usually the potting mix itself, but a fabric wick can be used too)

An overflow hole, so that if there's too much water, it can escape

How a Sub-Irrigation Planter Works

Think of how water moves up a sponge. Or put a piece of paper towel in water and watch the water move upwards.

The same thing happens in a self-watering planter.

The water that's stored in the reservoir moves up through the soil.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Plants That Thrive in Sub-Irrigated Planters

Annual vegetable and herb crops do well in sub-irrigation planters.

Avoid plants that are susceptible to root rot when overwatered. (For example, I grow potted lemon trees, and they hate “wet feet,” soil that says consistently wet. Read more about potted lemon trees.)

Potting Soil for Sub-Irrigated Planters

Choose a potting soil with good wicking properties. Do not use garden top soil or sand.

Sometimes this is easier said than done...because you won't find "wicking" on potting soil labels.

(A bargain isn't always a bargain when it comes to potting soil. If you see discounted bags at big-box retailers, be wary.)

The large compressed bales of potting mix made for commercial growers have a more consistently good quality. If in doubt, start with these.

If you're making your own peat-based potting mix, here’s an important point:

There are different qualities of peat. The darker peat from lower down in a bog is not as good at wicking as the lighter coloured, "blond" peat that comes from the top of a bog. Blond peat isn't always available at garden centres; you might need to go to an outlet that supplies commercial growers to find it.

Make Your Own Sub-Irrigated Planter

It's fairly simple to make your own self-watering planters.

Below is a series of pictures from a batch of planters I made for my garage rooftop garden.

The materials I used were inexpensive, and available at a hardware store:

Plastic storage bin

Weeping tile (4” bendable plastic drain used around the foundation of buildings…the term used for this seems to vary by region)

Dishwasher drain pipes

Landscape fabric

The tools needed to make these were:

Drill to make overflow hole

Saw or utility knife to cut the weeping tile and dishwasher drain pipe

Scissors to cut the landscape fabric

At the time I made these, I spent about $20 per planter, a fraction of what commercially available self-watering planters cost.

Making a Planter, Step by Step

Supplies to Make a Sub-Irrigated Planter

Plastic storage bin

Weeping tile (4” bendable plastic drain used around the foundation of buildings…the term used for this seems to vary by region)

Dishwasher drain pipes

Landscape fabric (not shown)

Weeping Tile with Fill Tube

Weeping tile coiled around the bottom of the bin.

A hole cut into the weeping tile with a utility knife allows a piece of dishwasher drain hose to be installed as a fill tube.

Landscape Fabric

The reservoir space created with the weeping tile is covered with landscape fabric so that potting soil doesn’t fill up the weeping tile.

Don’t Forget This!

Drill a drainage hole near the top of the weeping tile.

The hole shown here was too small…and was blocked by a piece of perlite, so i had to drill a bigger hole.

Recycled Items to Make a Self-Watering Planter

I've also made self-watering systems using materials from the recycling bin, or things we already had on hand.

Here are examples of items you can use:

For the Water-Tight Reservoir

Retrofitting a large plastic pot to make a sub-irrigated planter. The reservoir is made from old flower pots, which are covered with wire mesh. The wick (not shown) is fabric. The mesh is covered with landscape fabric so that the potting soil does not fill up the reservoir.

A water-tight container such as a pail

Or, a liner to make a water-tight area in a container with holes (for example, pond liner or construction plastic)

To Hold the Soil Above the Reservoir Area

Drainage pipe

Downspout extenders

Downspouts

Weeping tile

Upside-down flower pots

Landscape fabric, or old t-shirts

For a Fill Tube

Water bottles

Dishwasher drain hose

Pop bottles (“soda” bottles if you’re in the US)

PVC pipe

Retrofit Containers into a Sub-Irrigated Planter

A hypertufa planter with sub-irrigation.

You can retrofit any traditional pot into a sub-irrigation system…even if they have holes in them.

Use a liner to make a water-tight reservoir area at the bottom, and then create an overflow hole.

Planter Maintenance

Potting mixes lose structure over time as the organic matter decomposes. Plan to refresh the potting mix periodically. How often you need to do this depends on the mix, and the conditions. Pay especial attention to the soil in the lower area that acts as a wick.

If you're using a fabric wick, check it annually to see its condition. Fabrics made from natural fibres break down fairly quickly.

Sub-Irrigated Planter FAQ

How deep should a sub-irrigated planter be?

Making a sub-irrigated planter from a smaller, shallower planter. This is perfect for shallow-rooted crops such as leafy greens.

A soil depth of about 30cm (12") is usually lots. Remember, gravity is working against the wicking action...and when the soil is very deep the water doesn't wick all the way to the top.

The larger the plant you’re growing, the larger the volume of soil that you'll need. A smaller container with a 15 cm (6") soil depth can be fine for many smaller crops, such as leafy greens. If you're growing something that gets larger, for example bush-type tomatoes, a larger volume of soil is suitable. (That's why I used the storage bins in the example above. Along with determinate tomatoes, we use them for okra, peppers, and eggplant.)

Can I cover the soil on a self-watering planters?

Plastic mulch over the soil holds in moisture and deters squirrels from digging up transplants in the spring.

Yes. A plastic mulch holds in moisture and stops weed seeds from germinating. There are biodegradable plastic mulches that last for a single growing season.

Lay the mulch over the potting mix, and then tuck it in tight at the sides. Once it's snug, you can cut and X in it with a sharp knife, and then plant into the X.

A springtime challenge for us is squirrels digging up newly transplanted seedlings from our planters. A simple solution is the plastic mulch, which seems to deter digging. (Soil is out of sight, and it’s out of their wee little squirrel minds.)

Or, if you don't like the look of the plastic, burlap works well too. (It's a natural fibre, so doesn't hold in as much moisture, but it deters digging and reduces growth of weed seeds.)

What about watering plants in a SIP from above?

This is fine. It will keep the soil surface moister, so there's more chance of weed seeds germinating. But there's nothing wrong with this...other than it can be much slower than filling using a fill tube.

Can I reuse the soil in my self-watering planter?

Over time, as the organic materials in soil break down, potting soil loses its structure. When is has less structure (fewer bigger particles and fewer air pores) it doesn’t wick as well.

So for best wicking, fresh potting mix work best.

But...replacing potting mix every year is both wasteful and expensive. I usually mix in some new soil mix every year, about 20 per cent.

What is an Earthbox?

It is a well-known brand of sub-irrigated planters.

Is a “global bucket” a sub-irrigated planter?

Yes. I suggest you search online to find out more about this easy-to-make pail-in-pail SIP planter that has a reservoir.

What is a wicking bed?

With a wicking bed, we're taking the same ideas we use in a sub-irrigated planter—just on a larger scale. Now we’re talking about a raised bed. A wicking bed has a water reservoir, fill tube, and overflow just like a SIP does.

If you’re researching wicking beds, you’ll see that the names SIP and wicking bed are often used interchangeably. For me, if it’s a moveable planter, it’s a SIP. If it’s a permanent bed, it’s a wicking bed. But don’t sweat the lingo—as long as you understand how it works inside.

Find out more about wicking beds.

Are there any things to watch for with SIPS?

Yes, salt build-up. Normally, excess salts that can accumulate near the soil surface wash away with watering, and then drain from the bottom of a container. But with a SIP, we’re not washing down salts with water, and any runoff is captured.

That means it's a good practice to flush out your SIPs in the spring. Water heavily from the top, enough to cause lots of water to drain through the overflow holes and carry away excess salts.

How can I automate watering in my self-watering planter?

An irrigation spaghetti tube goes into the fill tube on the SIP.

You can set it up with automatic irrigation that refills the reservoirs.

You want what’s called “spaghetti tubes,” small tubes that run from an irrigation line. One tube goes to each planter. (This sort of system is often used to irrigate container gardens, with “drip emitters” at the end of each spaghetti tube to regulate how much water comes out and onto the soil surface in the container.)

But when you’re setting up spaghetti tubes and drip emitters for a SIP garden, just put the tube and drip emitter right into your fill tube, so that when you turn on the irrigation, you’re replenishing the water in the reservoir—not wetting the soil surface. (That way, less water is lost to evaporation, and you’re not creating conditions suited to weed-seed germination.)

Experience will teach you how long to leave on the water supply to fill up the reservoir.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More on Growing Vegetables

Articles and Interviews

Course

Get great ideas for your edible garden in Edible Garden Makeover. Planning. Design. Crops. How-to.

Garden Career Pivot

Thinking about a career in horticulture? Here’s more about the path I’ve taken.

By Steven Biggs

Working in Horticulture

I’ve had a number of readers and students ask about working in horticulture. Some are ready for a career change. Some are thinking about schooling.

But for me, working in horticulture involves going beyond working with plants and soil. It also include the internet and a way of expanding what I can earn in the field of horticulture. Read on to discover what I mean.

(And, yes, snails fit into my own story, as you’ll see below.)

The Great Snail Race

“There is a whole big family of snails I was just getting,” Keaton told me matter-of-factly.

He looked down at them as they moved from his cupped hand onto his shirt. The most daring of the snails was already halfway up his shirt.

But the adventures of the snail family didn’t end with the trek up Keaton’s shirt.

That slow climb up the shirt was just the beginning.

Keaton and the snails.

Next, the snail family sailed across a big puddle on our driveway, on a barely seaworthy scrap of wood. And once they’d sailed to the far side of the puddle, the adventures continued on the slide…with a snail race.

From Rat Race to Snail Race

I cherish that memory. It was a wet walk home from the schoolyard as Keaton collected all those snails.

At the time, my day revolved around walks to and from school. Morning drop-off. Midday drop-off. Afternoon pickup.

It wasn’t all snail races. I was at my desk working before the kids woke up. And between drop-off and pickup I’d snatch moments at my desk whenever I could.

The routine wasn’t something I imagined when I was at my previous job.

The routine was the result of an unwise (but fortunate) decision. I’ll tell you more about that decision in a moment.

But as a result of that decision I was out of the rat race. I was no longer a stressed-out commuter. I enjoyed small pleasures like snail races. And after wanting to quit the city, I was really enjoying city life.

I Started My Garden Work as an Imposter (At Least I Felt Like It)

It was 2006.

Even though the rat race was in the rear-view mirror, I hadn’t quite found myself. At least, I hadn’t convinced myself.

Asked about my profession, I’d hesitatingly respond, “garden and farm writer.” In hindsight, there was no need to hesitate.

My experience checked the right boxes:

I’d been a gardener since I was a kid. As a teen had my own gardening business. As a student I got a degree in agriculture and went straight into the horticulture industry. Check.

And in all of the jobs I’d had along the way, I’d been the person who would put together disparate bits of information into written guides and lists. I get a kick out of sorting and packaging information. Check.

Today

Keaton holding a copy of my first book, No Guff Vegetable Gardening.

My gig today is garden communications. I juggle a few things that relate to gardening and communications. I work as a college instructor, broadcaster, speaker, and writer.

I’ve been honoured to get recognition for my magazine articles, books, and broadcasting. And I was recognized as one of the “green gang” of Canadians making a difference in horticulture.

Most important for me is the flexibility. Almost all of what I do is online. That means I camp with my kids in the summer. If I want to go ice fishing for a day in winter, it’s my call. I can’t not work—but I can weave work around other important parts of my life.

Thinking of a Change?

There’s a need for people in the horticultural industry.

If you’re looking for horticultural work, here are just a few of the roles you can consider:

Landscaping

Landscape design

Greenhouse technician

Retail

Wholesale supplies

Research

Consulting

Here’s a neat apprenticeship option here in Ontario.

Want to grow food? Here’s a neat program near Toronto.

Deciding Who’s the Boss

A lot of people like being an employee: It gives structure and security.

There’s also the option of creating your own work. It’s the path that I followed.

And that brings me back to my unwise decision—the one I mentioned earlier.

How an Unwise Decision Turned Me Into a Garden Writer

My unwise decision was a career change. But I made it for a good reason: Balance.

I was aiming for more family time and less commuting time. To change the balance in my life, I left a job in agricultural marketing to work as a recruiter.

Why as a recruiter?

For no other reason than the office was a bicycle ride from my place. I wanted to be closer to home.

I figured that because I was good at working phones I would be fine in this phone-based work. But there was a problem: I was not good at it…

Months passed. I was still not good at it. Meanwhile, my wife Shelley was just about to wrap up maternity leave, and we weren’t excited about the prospect of daycare. Plus I needed to help my parents more.

It was a collision of life events—not any foresight on my part—that got me to take the leap. The leap from employee to self-employed.

One other thing really helped. An internet connection.

An Internet Connection can be a Gateway

Connecting with work on the internet is easier now than when I started. (I took an HTML coding lesson so I could manage my first website!) Things are much more user-friendly now.

But even though it’s more user friendly, an internet connection or a website or a social media following isn’t a guaranteed income. It’s just a gateway to other people.

So if you’re thinking of creating work, your challenge is to figure out what value you can provide.

First: Take Stock

What are you good at; and what are you not good at?

I suggest you make a checklist for yourself.

For example, my checklist at the time of the great snail race would have looked like this:

Growing food had become a big part of my life — the kind of thing to put on your list as you take stock of your unique experiences

Good on the phone (too much time spent as call-centre slave!)

Not good at being pushy with people

Write well

Can shut up and let people tell me their story (from working on a help desk)

Like to sniff around for leads (from a short career tangent into fraud prevention)

Know how to grow (I’d turned my small urban backyard into a mini farm)

So if you’re thinking of change, stop now and make your own list like this.

Jot down your life experiences. It may seem insignificant; it’s not.

Next: Take Time

As you think about how your different life experiences give you a unique perspective, be open to new ideas.

The final nudge into a garden-focused career arrived when I was on a plane. I unknowingly sat beside an editor for an online magazine. We chatted, and she asked if I wrote…

Then: Grow New Skills

If you want to give people value that they’ll pay for, you might need new skills, or to brush up on skills you have.

In my case, I took night school courses on writing and journalism. Then I joined a garden writer’s association, a farm writer’s association, and a professional writer’s association because I really didn’t know how to go about becoming a “real” writer.

You Might Feel Uncomfortable

I left the house for my first garden writer’s meeting feeling like a fraud. Then I nearly walked out the door when I arrived. It was a sea of grey hair. A bit intimidating for a 30-something. But I met another writer who I then collaborated with to write my first book.

At the first farm writer’s convention I went to, I felt like a misplaced urbanite. But I swapped business cards with an editor, and that led to a decade-long gig writing farm-business articles.

Keep Pivoting

On assignment writing a farm business article, with the kids.

Industries change. Work changes. And your personal needs will change.

When my kids were little I’d pack them up and take them out on assignment to write an article about a farm. We had a few fun adventures.

As they got bigger, I jumped into the topic of gardening with kids, and my daughter Emma and I did videos and books together. (You can see some of that here.)

Now they’re all teenagers. I have my workdays to myself—and I’m blogging and podcasting on a regular schedule. I’ve been honing my interviewing skills, and I love it.

When the pandemic came and people moved to online learning, I pivoted and started teaching my own online gardening courses.

It can feel uncomfortable sometimes, but put yourself outside of your comfort zone.

Set Your Expectations

My daughter Emma signing copies of her book Gardening with Emma.

I see lot’s of online get-rich-quick and passive-income schemes.

My experience is that I can sell something I create when it gives people value and when they want it.

Passive income is an fair goal: After I put the work into a book or online masterclass, there is some passive income from future sales. But there’s also ongoing selling needed. So it’s not entirely passive.

The other thing you’ll want to hash out as you set your expectations is just what you want. This brings me back to the idea of balance.

For me, balance looks like this these days:

Make 3 meals a day for my hungry teenagers

Time with my dad

Time in the garden (so I can write about it)

Write about what I love

Regular garage band practice

No social media apps on my phone

You’ll see my expectations go beyond income-earning activities.

With the expectations I set, I work long days. Some nights I’m teaching until 10 p.m. – then I’m up at 5 a.m. to blog before the morning maelstrom of household teenage emotions puts me in a haze.

Ultimately, the mix you choose should be emotionally and financially sustainable for you. And it should be something that you like enough you can keep doing it. (I’ve had writing assignments that were so painfully mind-numbing that I froze. They weren’t sustainable. I quit those gigs.)

Next Steps

So whether you’re an urban person focused on life balance that includes gardening, or a rural homesteader considering ways to add to the homestead income, here are two questions to start with:

Employee or self-employed

Online work or location-dependent work

As you’re thinking about those questions above, start your creative process:

Take stock of your unique experience and skills

Take time

Grow your skills

Be uncomfortable

Be prepared to pivot

Set your own expectations for success

25 Storage Crops to Help You Plan a Vegetable Garden that Feeds You Year-Round

25 storage crop ideas so you can plan a vegetable garden that supplies you with food year-round, even in cold climates, even if you don’t have a greenhouse.

By Steven Biggs

Plan a Vegetable Garden that Includes Storage Crops

I have a plan to turn a room in my basement into a proper root cellar. Braids of onions hanging from the ceiling, homegrown squash on shelves, lots of root vegetables…

But I don’t have a root cellar at the moment.

Maybe it’s the same for you.

The good news is that you can store a lot of homegrown food even if you don’t have a root cellar.

And having lots of vegetables to store starts with your vegetable garden planning. Choose crops that you can store in the garden. And choose crops that store well in protected areas other than a root cellar.

This articles helps you plan a vegetable garden with storage crops in mind.

Storing Crops

Pin this post!

I like to think of crop storage two ways. I recommend a bit of each in your vegetable garden plan.

In-Garden Storage: Leave cold-tolerant crops in the garden to continue harvesting as the growing season wraps up.

Harvest and Store: Harvest crops and store in a protected space.

In-Garden Storage

When cool weather arrives, some plants pack it in and die. Think of basil…a little sniff of cold and it drops its leaves in protest.

But some crops do very well in cool temperatures. They soldier on even as fall frosts arrives.

Even with these cold-tolerant crops, growth slows down and stops as days get shorter and shorter. But you can continue harvesting what’s there.

Leafy Greens for In-Garden Storage

Here are my favourite leafy crops for in-garden storage. And to be clear, I’m not suggesting that I harvest any of these winter-long here in Toronto. I don’t. But they have good cold tolerance, and I’ve often picked them from under a dusting of snow.

(If you want to take you year-round harvesting to another level, think of using a combination of cold frames and cold-tolerant crops.)

Kale is very cold-tolerant. If you can only grow one cold-tolerant green, start with kale.

Kale. For cold-climate gardeners, kale is a great season extender. It’s very freeze tolerant. It keeps going as light frosts arrive in the fall. Then as things freeze hard, it still hangs on. I’ve sometimes picked kale in January from under the snow. (The winter-harvested leaves are a far cry from tender, baby kale, by the way. But if you cook it accordingly, it’s a great homegrown addition to the menu.)

Celery. Reliable until hard freezes arrive. (And if you’re thinking celery isn’t a leafy green, you’re right. Except my favourite type of celery is “leaf” celery. Leaf celery, as the name suggests, is more leaf, less stalk—and it’s far less demanding and easier to grow than regular celery.)

Chard. Reliable through those first fall frosts, until hard freezes arrive. Chard also looks great, so if you’re interested in edible ornamental gardens, consider this as you plan your vegetable garden. (Maybe you have ornamental beds that would benefit from a pop of fall colour from one of the many colourful chard varieties.)

Parsley. Reliable until hard freezes arrive. Like chard, also a great ornamental plant. Use it as edging alongside annuals somewhere near your house, so that during muddy fall weather, it’s easy to quickly grab a few sprigs for supper.

Parsley stands up nicely to fall frosts.

A Couple More In-Garden Storage Crops

Keep harvesting cardoon until there’s a hard freeze.

Leek. Like kale, a plant you can keep harvesting into winter. And when there’s a mid-winter thaw, you can go get some more. The leaf tips begin to brown mid-winter…but that’s fine because it’s the lower portion we eat.

Cardoon. Cardoon keeps going through light frosts. It’s leaves wilt, and then spring back up as the day warms. (If you haven’t grown cardoon before, remember to blanch it or it’s horrid…my first forays into cooking cardoon didn’t win me any favours with my family!)

In-Garden Storage Using Straw Bales

As fall frosts arrive, there’s no rush to harvest many of the in-ground root crops. Carrots and parsnips are improved by frost.

A simple way to extend the time you can leave them in the ground is to place a straw bale over top of them. It insulates them and the ground below.

With a heavy mulch, you can leave carrots and parsnips in the ground until the soil freezes solid. Where I am, that’s midwinter. And the longer they’re in the ground, the better they last.

One more thought on leaving roots crops in the garden late: Remember that while carrots and parsnips usually grow under the soil and protected from the first freezes, beet roots often shoulder their way above the soil surface. Those exposed shoulders are quicker to freeze…and that affects the quality.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Harvest-and-Store

First things first: A root cellar is nice…but if you don’t have one, there are other ways to successfully store your harvest. Think about your storage options now, as you plan a vegetable garden. That way you can plant accordingly.

Here are different places you might be able to store your harvest:

Swiss chard with some frost on it. It will spring back up once the sun comes out.

Garage. My garage doesn’t freeze, so I use it to store root crops (and apples that I buy by the bushel…great way to save money). My garage stays just above freezing, and is fairly humid, making is well suited to storing produce.

Clamp. This is a traditional way or insulating harvested root vegetables outdoors, using soil and straw.

Cooler area in a heated basement. I have a room in my basement where I shut off the heat vents. It’s cooler (and darker) than the rest of the house. It’s not as humid or cool as a proper root cellar, but is excellent to store winter squash, garlic, and onions.

Unheated basement. A friend had an unheated basement with an earthen floor…perfect for stored crops!

Sunroom. If you have a sunroom that stays just above freezing through the winter, I’d be thinking about food storage…

Breezeway. Some houses have a minimally heated breezeway between the house and garage. It’s just calling out for food storage!

Attic. If you have an accessible attic, another option for cool storage! The logistics of carrying food up to an attic aren’t ideal, but if it’s all you have, worth a try.

Successfully Storing Crops

Storing crops in the right conditions can really extend the storage life.

Root crops can go into perforated plastic bags, or into moist sand or sawdust in crates. This prevents them from drying out.

Newspaper comes in handy too: cover trays of green tomatoes with a sheet of newspaper; and wrap cabbages in a sheet of newspaper.

Only store unblemished produce. If you have crops that aren’t good enough to store, cook them up or freeze them.

Harvest-and-Store Crops

Dry Bean

When the pods turn light brown, just pull up the entire plant to hang upside-down under cover to dry further. Great storage crop for long-term storage.

Beet

Leave a half inch of stem on the roots as you prepare to store beets. Then they won’t “bleed” as much. Look for varieties recommended for storage. A favourite of mine over the years has been ‘Cylindrda.’

My favourite storage crop! (I make beet borsch with some of mine every year.)

Cabbage

Not a crop that lasts all winter in a root cellar, but you can keep it for a couple of months. The outer leaves dry, and you’ll peel those off as you prep the cabbage for use in the kitchen.

Use midsummer transplants to grow cabbages for winter storage. Harvest as late as possible for storage.

(Don’t forget that you can also use some cabbage to make sauerkraut. Find out how to make your own sauerkraut.)

Cabbage, along with other cole crops such as broccoli, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts are also excellent for in-garden storage as they keep going through early fall frosts.

Carrot

Use midsummer transplants to grow cabbages for winter storage. Harvest as late as possible for storage.

Sweeter after some frost. Look for varieties recommended for storage. ‘Bolero’ is a variety that I like for storage.

Cerleriac (a.k.a. celery root)

Often overlooked, and a great addition for gardeners growing for storage.

Garlic

Easy to grow lots in a small space, and easy to store for gardeners without many storage options, because it and onions like things dryer than the root crops.

Horseradish

As you’re planning your vegetable garden, remember that this is a deep-rooted perennial. So pick a permanent spot for it.

Jerusalem artichoke

A somewhat invasive perennial, so pick a permanent spot for it.

Onion

Braided onions drying before going into storage.

Store onions after curing. Like garlic, important to dry and cure for a couple of weeks before storage. If not properly cured, doesn’t last as long.

You don’t have to braid onions. Another way to store them is to hang them in a mesh bag—so there is good air circulation around the onions.

Parsnip

Sweeter after they go through some frost.

(One year I grew far too many parsnips, and had the brilliant idea of making parsnip wine. Alas, it was horrid…couldn’t even use it as cooking wine.)

Peppers

Often overlooked, but smaller, thin-skinned pepper varieties are easy to dry. Once dry, you can hang them in your storage area, where there’s good air circulation.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Potato

Plan for your storage potatoes to be ready late in the season. During the summer, storage spaces aren’t usually as cool as they are in the fall—so your potatoes can sprout quickly when stored too early.

Don’t put early potato harvests into storage. Plan for a later harvest for storage.

Radish (winter)

So often overlooked, and a great addition in a storage-focused garden.

Root Parsley

Ditto above.

Rutabaga

My mother-in-law’s must-have cooked veg at the Thanksgiving table!

Squash

Pick before light frosts for best storability.

Tomato (keeper)

Keeper tomatoes in the spring.

It’s easy to overlook tomatoes as a storage crop, but there are thick-skinned tomato varieties that can last until spring! They’re called “keeper” or winter tomatoes or storage tomatoes.

These aren’t great for tomato sauce, but are nice chopped into a salad or bruschetta.

Find out about keeper tomatoes.

Find out my top tips for starting tomato seeds indoors.

Get ideas for different ways to stake tomatoes.

Learn about ripening green tomatoes indoors.

Turnip

A quick-to-mature crop. Remember, the greens are edible too!

Watermelon

Watermelons last a month or so, a nice treat to stow away for a snowy day!

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

Want Green Veg Over the Winter?

Find out how to grow microgreens indoors.

Need More Ideas to Plan a Vegetable Garden?

Articles and Interviews

Hear an agronomist share top tips for winter vegetable gardening.

7 Vegetable Garden Layout Ideas To Grow More Food In Less Space

Courses on Edible Gardening

5 Types of Cherry Bush to Grow in Edible Landscapes and Food Forests

5 types of cherries to grow as a bush in an edible landscape. Evans cherry, University of Saskatchewan bush cherries, chokecherry, Nanking cherry, Pin cherry

By Steven Biggs

Grow Cherries in an Edible Landscape or Food Forest

A cherry bush is a great addition to an edible landscape or food forest. Here’s a Nanking cherry bush.

The noise!

If you’ve grown cherries, you might have had a flock of birds descend on a cherry tree. Starlings, especially, are so loud that I wonder how they manage to eat and squawk at the same time.

But they do. And they clean out a tree quickly.

The gardener can watch (and listen) – or, go look for a ladder to get up there and compete with the birds for the cherries!

A ladder… Who needs the bother of a ladder in an edible landscape or a food forest?

In a home garden or landscape setting, simplicity is key. Ladders are not simple. Nor are fruit trees that need shaping and regular pruning.

Luckily, there are a number of cherries that grow as bushes.

Some have larger fruit that you can pop right into your mouth. Others, long prized by foragers, have smaller fruit suited for jams, jellies, juices, and wine.

Keep reading for bush cherry crops you can add to your garden.

Benefits of a Cherry Bush vs. a Tree

A bush makes a lot of sense in a home garden or edible landscape.

When you have a bush with multiple stems, you can renew it by lopping of some of the stems so that new stems take over

More branches means more yield

Cherry insurance! (More branches means more chance of some surviving a challenging winter)

Foil the birds…because a bush is easy for you to quickly pick (and easier to net if you’re so inclined)

Cold hardiness, because low-growing branches are insulated by snow

In this article, I have 5 different cherries that you can grow as a bush in your edible landscape or food forest.

These all grow on their own roots (so no grafting required), and are all self-fertile—so you don’t need to worry about growing two varieties to get fruit.

Forget the Ladder…Grow a Cherry Bush

Dwarf Sour Cherry Bushes…from Saskatchewan

The University of Saskatchewan fruit breeding program has produced some great high-yielding hardy bush cherries. (So good that even the BBC wrote about them!)

The bush-like form and the high-quality fruit is the result of breeding Mongolian cherry with European sour cherry.

The bush-cherry cultivars in the University of Saskatchewan “Romance” series have different bloom times, bush size, and fruit colour.

Here are the cultivars:

Carmine Jewel

Romeo

Juliet

Valentine

Cupid

Crimson Passion

Here’s more about the story behind these cherries.

Here’s where you can find out more about ripeness.

Hear bush cherry expert Bob Bors talk about cherry breeding and haskaps at the University of Saskatchewan. https://www.foodgardenlife.com/show/grow-haskap

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Evan’s Cherry in Alberta

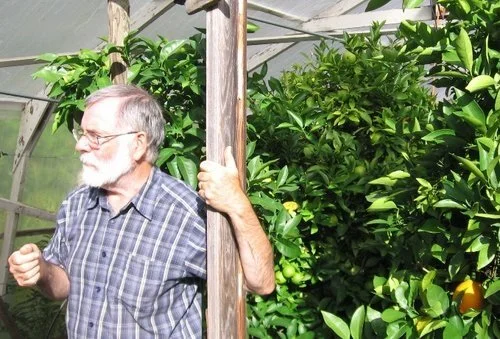

Dr. Ieuan Evans with Evans cherries.

Prunus cerasus

When Dr. Ieuan Evans moved to Alberta, he was disappointed to find very few people growing fruit.

But he heard about a very fruitful cherry tree near Edmonton, so he visited – and got pieces of it to propagate. (Just in time, as the property was slated for redevelopment.)

He gave away rooted suckers of this fruitful cherry as fast as he could grow them. It was very cold hardy AND very fruitful.

What’s now known as Evans cherry is an especially cold-hardy cultivar of the European sour cherry.

It can grow as a tree or a bush.

Hear Ieuan Evans talk about finding the Evan’s Cherry in Alberta.

Nanking Cherry Often Overlooked

Nanking cherry bush in flower.

Prunus tomentosa

This is the cherry bush that my grandfather grew in his Calgary yard.

It’s compact, extremely fruitful – and a beautiful addition to a landscape. I grow it in my front yard, and when it blooms, pedestrians always stop to take selfies in front of it.

These small sour cherries are delicious fresh. They’re also great for use in the kitchen. I like to make them into a cordial.

The fruit is smaller than the University of Saskatchewan and Evan’s cherries. But they’re absolutely prolific.

I have an article all about them. Find out more about Nanking cherry.

Chokecherry (a.k.a. Choke Cherry)

Chokecherry fruit grow in easy-to-pick clusters.

Prunus virginiana

Chokecherry is a native north American species that grows as a bush or small tree. There are a few cultivars, but most people know it because wild chokecherry plants arrives in gardens uninvited—thanks to critters that drop the seeds.

I have a patch of chokecherry in my garden. When a purple-leafed plant appeared, it was the perfect addition to an otherwise underused corner of my garden.

The flowers of chokecherry are a cluster that looks a bit like a bottle brush. And when those flowers become fruit, the pea-sized fruit are all in an easy-to-pick cluster.

This astringent fruit is aptly named. It has supreme pucker power! With processing though, the fruit is delicious. Use them for juice, jam, and syrup.

Hear Quebec agronomist Laurie Brown talk about growing and using chokecherry.

Chokecherry flowers

Pin Cherry (a.k.a. Pincherry)

Brightly coloured pin cherries light up the landscape!

Prunus pensylvanica

Pin cherry is another native North American species that grows as a shrub or small tree. I love the smooth, brownish-red bark.

Like chokecherry, the fruit are small. They’re more suited to fresh eating than chokecherry, giving you a tasty sour cherry taste without all the astringency.

While chokecherry flowers and fruit grow in a bottle-brush-like cylinder, pin cherries are on long, slender stems, with a few stems attaching to a branch in the same spot.

The bright red cherries light up a landscape. Use them to make jelly, juice, syrup, and wine.

Bush Cherry FAQ

Can I swallow the seeds?

All cherry seeds contain a cyanide compound, and consuming large quantities of fruit without removing seeds can make you sick. So spit out the pits!

Can I grow cherry bushes near a black walnut tree?

If you are dealing with black walnut toxicity, a.k.a. juglone toxicity, try growing cherries. Members of the Prunus family cope nicely with the juglone that’s given off by black walnut trees. Here’s a guide to gardening near a black walnut tree.

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

More on Fruit and Edible Landscapes

Articles

Interviews

Courses

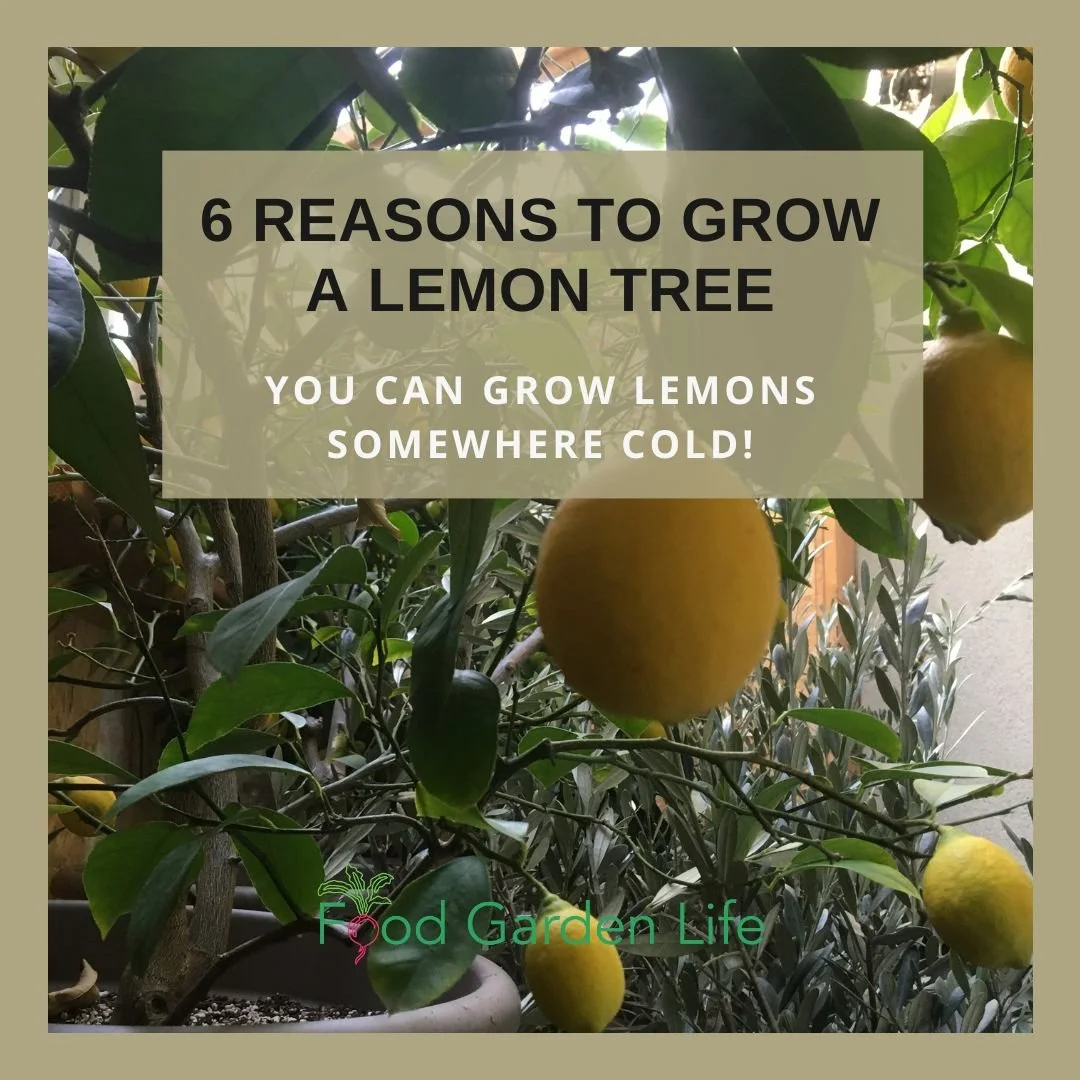

Guide: How to Grow Lemon Trees Indoors That Actually Produce Lemons

Find out how to grow lemon trees indoors (and get lemons!).

By Steven Biggs

Can You Grow a Lemon Tree Indoors? Sure!

If you’ve seen lemon trees growing outdoors in warm climates, you might be wondering how you can grow a potted lemon tree indoors, without it getting too big.

Many lemon varieties grow into small trees when grown in the ground outdoors in warm climates.

(Keep this in mind if you plant a lemon tree in the ground in a greenhouse – it can get big!)

If you know a few simple things about how lemon trees grow and how to care for them indoors, you can enjoy the fragrance of lemon flowers and harvest your own lemon fruit indoors.

This guide to growing a lemon tree indoors explains what you need to know.

Lemon Tree Size

You can keep a lemon plant small. When it comes to the ultimate size of your lemon tree, remember that as the gardener, you’re the boss. You’re the one with the pruning shears!

Here are things (besides pruning shears!) that can affect the size of your lemon tree indoors:

Most commercially produced lemon trees are grafted. That just means that a piece of a lemon variety with nice fruit is attached (“grafted”) onto another variety that has roots with desirable traits (a.k.a. the rootstock). Some rootstock varieties have a dwarfing effect, keeping the lemon tree smaller. (A common dwarfing rootstock is called ‘Flying Dragon’).

If you have grown a lemon tree from seed, or your lemon tree is a rooted cutting, it will be growing on its own roots. There’s a good chance it will get bigger than lemon trees grafted onto a dwarfing rootstock.

Pot Size

This potted lemon tree is over 50 years old. Pruning and pot size keep it compact.

The smaller the pot, the smaller the lemon tree.

Think of how bonsai trees that are hundreds of years old can grow in very small pots.

It’s a combination of a small pot, along with root and stem pruning that will keep your citrus trees small.

Lemon Variety

There are many lemon varieties—just like there are many apple varieties. As well as differences in the fruit, there can be differences in the way the plant grows. Some are more compact than others.

A good example is the Meyer lemon tree, which is naturally dwarf and more bush-like than many other lemon varieties. (Meyer lemon trees are actually a hybrid that has some tangerine genes in its bloodline!)

(I think a potted Meyer lemon tree is a great starting place for first-time gardeners. They're compact, and very fruitful. I've harvest 50 lemons from a knee-high potted Meyer lemon tree.)

Indoor Lemon Tree Leaf Drop

A lemon tree that’s been growing in cool, humid fall conditions outdoors will often drop leaves when brought indoors for the winter. It’s ugly…but common. They grow back.

Lemon plants are evergreen, meaning that they have leaves on them year-round.

It is common for some leaves to drop off as the temperature and light levels change with the season.

(Especially if you have a potted lemon growing in cool, humid autumn conditions outdoors and then you bring it into the dry air of a centrally heated home. It might just drop its leaves in protest!)

What Kind of Light do Indoor Lemon Trees Need?

Bright light is best. Look for a location that has at least 8 hours of bright light per day. That usually means a south-facing window.

When the lemon tree is growing in full sunlight, the growth is more compact, and there will be better fruiting and flowering.

If you don't have bright natural light, try a grow light. (I've seen pictures of an indoor lemon tree doing very well under a grow light...in the Yukon!)

Indoor Lemon Tree Harvest

Lemon trees have flowers and fruit at the same time. Pictured are fruit at different stages of maturity.

Lemon is one of my favourite citrus trees because lemon trees can have fruit and flowers at the same time. That means that while you’re enjoying the smell of lemon blossoms, there might also be small immature fruit on your lemon tree—and some larger ones.

Ripe lemons can remain on the plant for many weeks. There’s no rush to harvest them.

The size of the lemon harvest you can expect depends on a few things:

Variety

Plant size

Growing conditions

Season length

Indoor Lemon Tree Pollination

Pollinate flowers on lemon trees growing indoors using a small paintbrush.

Do you need 2 lemon trees to get lemons? No!

Every lemon bloom has male and female parts. They are also “self-fertile,” meaning you don’t need pollen from a different lemon tree to get pollination.

Outdoors, wherever there is a breeze, or a bee, pollen from the male part naturally drops or is transferred onto the female part of the flower and a small fruit starts to form.

Indoors, use a small paintbrush to transfer pollen between flowers.

Partially or imperfectly pollinated blooms can form fruit that drops off early. Not enough water can also cause small fruit to abort.

Tip: Lemons can make a lot of flowers in a cluster. Sometimes up to 12-15 booms. If they all become lemons, it’s a lot of work for the plant. Thin out the little lemons to 3-6 fruit per cluster.

Lemons can make a lot of flowers, sometimes 12-15 booms in a cluster. Thin out the little lemons to 1-6 fruits per cluster.

Indoor Lemon Tree Care

Watering Lemon Trees Indoors

When lemon trees are watered too often, the roots rot. Healthy roots are bright, like the ones pictured.

Top tip for indoor lemon tree care: Watering is the #1 key to success for indoor lemon trees.

Lemon trees don’t like to be in continuously wet soil. They hate having “wet feet”. Too much water can rot the roots.

After watering, the soil at the bottom of the pot remains quite wet until your lemon tree draws on that water – so don’t just water when the soil at the top of the pot looks dry.

When watering your potted lemon tree, touch the surface of the soil, and put your finger into the soil to see if it’s moist below. A good rule of thumb is to keep the soil on the dry side of moist.

In doubt? Pick up the pot to feel how heavy it is.

Frequency of watering will depend on:

Soil

Pot type

Plant size

How fast the plant is growing

How dry the air is

Temperature (and, yes, heated floors will definitely cause the soil to dry out more quickly!)

Keep Your Lemon Tree Through the Winter

And enjoy fresh homegrown lemons!

Pruning an Indoor Lemon Tree

Prune lemon trees so branches are well spaced.

Here are some general pruning tips for lemon plants:

Remove crossing branches

Prune so branches are well-spaced

Cut back to a bud or a branch

Remove fast-growing, upright branches (water shoots)

Remove suckers coming from below the graft union on grafted plants

Indoor Lemon Tree Pests

An indoor lemon tree can get the same pests as an outdoor one...but indoor conditions are often better for the pest!

The two most common pests of indoor lemon trees are:

Scale on an Indoor Lemon Tree

The adult stage of scale insects are immobile and have a shell. Scrape them away with your fingernails, or use a cotton swab soaked with rubbing alcohol.

Scale insects can be dabbed away individually with a cotton swap dipped in rubbing alcohol. If the outbreak of scale is larger, try rubbing them off with your fingers, spraying the tree with a high-pressure water source, or using a biological control such as a predatory mite.

Before noticing scale, you might first notice sticky spots on the floor below, or a dark, sooty coloured film (mould) on leaves. Scale insects give off sticky liquid, and that’s the cause of the sticky spots below, and the mould, which feeds on the liquid. Wash leaves with a soft cloth to remove sooty mould.

Spider Mites on an Indoor Lemon Tree

Watch for spider mites when growing lemon trees indoors. They’re hard to see without a magnifying glass…you might only see little spots moving on a leaf. If leaves begin to look stippled, check for spider mites.

Spider mites do well in the dry air in centrally heated homes. Higher humidity helps minimize leaf drop and make conditions less suited to spider mites

Seasonal Moves for a Potted Lemon Tree

Pin this post!

Moving Your Indoor Lemon Tree Outdoor for Summer?

Gradually harden off plants in the spring over a period of a couple of weeks. Don’t go cold turkey and put them in full sun without hardening them off or there can be sun scald and wind burn.

Moving Lemon Trees from Outdoors to Indoors

If you’re bringing a potted lemon tree indoors for the winter, consider moving it indoors earlier rather than later, so there is less of a drastic change in temperature and humidity. This helps to minimize leaf drop.

While the fragrance of the flowers makes it nice to have lemon trees in a bright kitchen or living room window, your lemon tree does not need to be at room temperature. It will do better in cooler temperatures.

Here are examples of protected spaces that have cooler temperatures:

A bright attic window

A sun room (it does not need to be fully heated, keep the temperature just above freezing)

Find Out How to Grow Your Own Lemons

Harvest more lemons this year. Grow Lemons in Cold Climates Masterclass shows you how to grow a lemon tree in a pot or outside with protection. And get lemons!

Pots for Indoor Lemon Trees

Do not us pots with reservoirs (“self-watering” or “SIP”). This is because this sort of pot keeps the soil constantly moist…and lemon tree roots can rot in wet soil.

A decorative pot with no drainage holes is a recipe for soggy soil and root disease. Make sure to select a pot with drainage holes so that the roots don’t rot!

Lemon Tree Pot Size

When deciding on pot size, consider:

The size of pot you can move

Young plants that have not attained the final desired size can be moved to a bigger pot annually, early in spring or early summer once the roots fill the current pot.

Whether the roots are likely to quickly fill the pot. “Overpotted” lemon plants (plants in pots that are too big) won’t use up soil moisture as quickly—so there is more chance of root rot.

Repotting Lemon Trees

Covering everything from lemon varieties, to location and watering, to pruning and shaping, to overwintering, dealing with pests, and more—and including insights from fellow citrus enthusiasts—this book will give you the confidence you need to grow and harvest fresh lemons in cold climates.

Mature plants don’t need to be repotted annually. Remove and replace the top few centimetres of soil every couple of years.

Soils break down over time and air pores collapse, so you will eventually want to repot the plant in new potting soil.

Lemon Tree Potting Soil

If you’re moving your lemon tree outdoors for the summer, a heavier soil can prevent the pot from tipping over in the wind.

Here’s what I do for potting soil:

For young plants that are growing quickly and that I’m moving to bigger pots regularly, I use a lightweight soilless potting soil. It’s great for fast-growing plants.

For lemon plants that have reached a size I want to keep them at, I add some garden loam to my potting soil for added weight (so they don’t tip over when I put them outside for the summer.)

The potting soil products available to you will depend where you are. The key thing is to tailor your watering to the mix you’re using—and don’t over-water. (I spoke to a grower who make a very well-drained mix because he found he was always heavy-handed on the watering!)

Indoor Lemon Tree Fertilizers

Potted lemon plants must be fed! You’re getting a small amount of soil to support all that plant and fruit development.

Start feeding in the spring, as plants begin to grow. Cut back on feeding in late summer as cooler temperatures and less light cause plant growth to slow.

There are many fertilizing products on the market, both organic and conventional. And each lemon grower has a favourite formula.

Not sure where to start?

Look for “all-purpose” or “general-purpose” product. Make sure it has micronutrients

Decide what suits your style of gardening (do you want to mix solutions regularly – or apply slow-release fertilizer granules just once in the spring)

More on Micronutrients and Potted Lemon Trees

“Interveinal chlorosis” (yellowing between leaf veins) on a lemon tree.

Micronutrient deficiencies are common with lemons. So make sure the fertilizer contains micronutrients.

“Interveinal chlorosis” is a fancy way of saying yellowing between the leaf veins. And it's a common thing to see on lemon tree leaves.

It's often iron, zinc, or manganese deficiencies. These deficiencies can even occur when the micronutrients are present in the soil, but the soil is too alkaline. That alkalinity prevents the lemon plant from taking up the micronutrients.

What to do for Micronutrient Deficiencies in Potted Lemon Trees

Forget lab analyses. Here are some other things you can do:

Use elemental sulphur to lower the soil pH. Available for home gardeners at garden centres.

Occasionally use a water-soluble fertilizer for acid-loving plants.

Some areas have a lot of lime in the water, and it builds up in the potting soil with repeated watering. So just repot your lemon more often.

Flying Dragon rootstock is intolerant of lime – so you might find lemons on their own roots are less troubled by high pH than grafted lemons on Flying Dragon.

Growing a Lemon Tree FAQ

What should I do if I don’t have full sunlight?

Ripe lemons last a long time when left on the the tree.

If you’re growing your lemon tree inside year-round, this can be a problem. You might want to add supplemental light, or grow your lemon under artificial lights.

But…if, like me, you put your lemon tree outdoors for the summer, think of indoor overwintering as simply a way to get your tree to survive the winter.

What about other citrus plants?

Another favourite citrus tree of mine is yuzu, a very cold-tolerant citrus with a very fragrant rind. It grows very well in a pot—and the fruit are very useful in the kitchen. Another very cold-tolerant fruit tree is mandarin orange.

How long can I leave homegrown lemons on the tree?

They last weeks, often months, on the tree. Don't pick what you're not ready to use.

What can I do with my Meyer lemons?

Lemons lined up to process into lemon curd. Meyer lemon curd is my favourite!

Lots of Meyer lemons is a good problem to have. My favourite uses are Meyer lemon curd, or sorbet.

How long before my indoor lemon trees will produce fruit?

Seed-grown fruit trees go through a juvenile stage where they don't bear fruit.

But a rooted cutting or a graft from a mature fruit tree can bear fruit right away. I've seen a six-inch tall lemon tree flower and form fruit. (My recommendation is to pick it off, so that energy is used to grow the plant bigger.)

Can I grow Meyer lemon trees from seed?

If you grow a lemon tree from seed it will likely grow up to be like the parent plant. (This doesn't happen with many fruit trees, apples are a good example of fruit trees that have offspring different from the parent plant.)

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

Keep Your Lemon Tree Through the Winter

And enjoy fresh homegrown lemons!

More on How to Grow Lemons

Guide to Making the Best Borsch

Recipe for the best borsch, just like Mom made! Here are my 2 must-have ingredients, and tips on making a great stock for your homemade borsch.

By Steven Biggs

How to Make the Best Borsch

When Mom served her homemade borsch we’d empty the pot. It was rich, filling, tangy – and always topped with a dollop of sour cream or “smetana.”

Her borsch was different every time, because she used what she had in the kitchen, and in the garden or cold cupboard.

But it always had beets.

Garden-to-Table Cooking…in Winter

I think about borsch as I plan my vegetable garden because it’s full of vegetables that store well.

Beets, carrots, onions, and garlic all keep well in a cold room or root cellar.

(Mom sometimes used dried lima beans, another food that stores well.)

Borsch Backstory

There are many variations on borsch.

Make the best borsch! Most recipes use red beets, but if you’re growing yellow or white beets, you can use these too (but the final colour of your borsch will be different.

Some are thicker and stew-like; some more soup-like. Some are tarter; some are sweeter.

It’s eaten hot or cold.

There are summer and winter styles, depending on what’s in the garden.

It’s not just the ingredients and cooking styles that vary: So does the spelling of the name. You might come across borscht, borsch, bortsch, borstch, borshtch, borsh, or borshch.

That’s because it’s a staple in many Eastern European cultures.

What most variations share is lots of chopped veggies—especially beets. And there’s usually a combination of tangy and sweet.

Depending on the recipe, the tanginess might come from vinegar, sour cream, sauerkraut, kvass (a drink made from fermented grains), or lemon juice.

The Stock for Making Borsch

Mom’s borsch was decidedly full of meat. The stock depended on what she had on hand.

I simmer a ham bone or smoked pork hock for the better part of a day to get a rich stock.

You can also make a great borsch using vegetable stock. (See the recipe below.)

Essential Ingredients

Here are two ingredients that I love in borsch:

Dill

Sour cream

When there’s fresh dill available, I always use it. Through the winter, I use chopped, frozen dill saved during the summer.

Sometimes I also add dill seed—which is like little nuggets of dill flavour. Use dry dill seed in the winter, and in the summer, try fresh dill seed.

Sometimes a dollop of sour cream is served atop a bowl of borsch. I like that…but I also like to mix a bit into the borsch when I’m almost done cooking to give a tangy, creamy finish.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Pin this post!

Top Borsch-Making Tip

During cooking, you lose colour contrast as the ingredients in your pot of borsch all take on the red colour of the beets.

So create contrast in texture by chopping the different vegetables into different sizes and shapes. (I like long, thin strips of cabbage!)

Then, when it’s serving time, the dollop of sour cream on top is like a white island in the sea of red. If you top this combination with fresh chopped dill, you’ve added two more colours to your ruby-coloured soup.

Serving Ideas

Toasted, buttered rye bread is all that you need with a bowl of borsch. I love a caraway rye bread (which has caraway seeds in it.)

Storage

I make soup by the pot. I keep enough in the fridge for the week, and then freeze some to use at a later time.

Beet Borsch Recipe

Ingredients:

The Veggies

Remember, chop the different veggies in different ways to create texture. The quantities below are approximate. Vary it up depending on what you have on hand, what you like, and the size of the veggies.

6 medium beets, peeled and chopped

¼ - ½ head of cabbage, shredded

2 onions, chopped

2 large carrots, chopped

1 stalk celery, chopped

1 leek, chopped

1 potato, peeled and chopped

3 cloves garlic, crushed

Liquid

4 cups water

1 tbsp. vinegar

2 cups stock (I make mine from a ham bone or smoked pork hock, but you can use chicken or vegetable stock, depending on your preference)

Herbs and Spices

3 tbsp. chopped dill

½ tsp. caraway seeds

Salt and pepper to taste

Thickener

½ cup sour cream or kefir

1 tbsp. flour

Optional

½ cup dry lima beans

Or, if you have shelling beans in the garden, substitute these for the lima beans

I like to chop up and add the beet leaves and stems to the soup too

Directions

Soak lima beans in water overnight

Combine chopped vegetables and liquids in a large pot

Cook over medium heat

Add vinegar as soup begins to boil

Simmer for a couple of hours, until the vegetables are soft

Add dill, caraway seeds, pepper, and salt

Simmer for a few more minutes

Final but important step: The flour thickens the borsch just a little bit. Mix flour into the sour cream or kefir, and then stir this mixture into the soup and simmer for a couple of minutes. (Don’t add the flour straight to the boiling soup or you might get little dumplings!)

Find This Helpful?

Enjoy not being bombarded by annoying ads?

Appreciate the absence of junky affiliate links for products you don’t need?

It’s because we’re reader supported.

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re glad of support. You can high-five us below. Any amount welcome!

Gardening Courses

More Food and Recipe Ideas

Force Rhubarb Indoors

Force rhubarb indoors and harvest tender, pink rhubarb mid-winter while the snow flies outdoors.

By Steven Biggs

Force Rhubarb Indoors for a Mid-Winter Harvest

Rhubarb and candles?

One day I got chatting with my neighbour’s fence installer, who was interested in my garden.